During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Bencharong porcelain was considered Thailand’s most valuable ceramic ware and is still widely celebrated in Thai culture today.

First commissioned by the royal Thai court from the late Ayutthaya period (1351-1767), Bencharong wares were produced in a variety of shapes, colours, and sizes, featuring both religious and secular motifs.

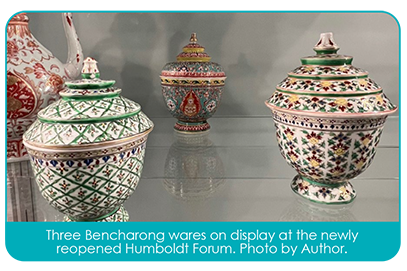

Three Bencharong wares on display at the newly reopened Humboldt Forum.

These pieces are instantly recognizable for their bright palette, geometric patterns, and frequent appearance of Thai Buddhist scenes. The name “Bencharong” means “five colours” in Thai; however, most Bencharong palettes range from three to eight colours.

The Bencharong palette first included yellow, black, white, red, and turquoise. Later, blue, orange, purple, and pink increasingly appeared.There is more than meets the eye, however, as this quintessentially “Thai” form was crafted entirely in China at Jingdezhen!

The most common theory for Bencharong’s name cites a literal translation from Bencharong’s Chinese Ming predecessor, wucai (“five colours” in Chinese). Another theory links the name to bencharongse, a Thai cotton dyeing technique with a similar five-colour palette, dating to the Sukhothai period (1238-1438).

Techniques

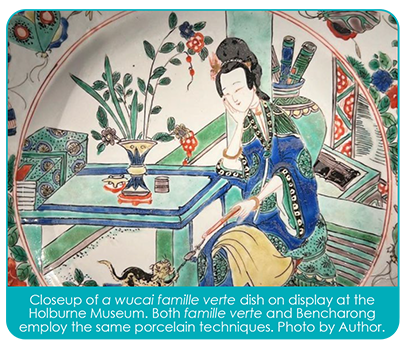

Bencharong techniques closely resemble those of Ming and Qing wucai (sometimes called yingcai in the Qing Dynasty or famille verte, noire, or jaune). Like Bencharong, wucai was also glazed, double fired, and decorated with three-to-eight polychrome enamels.

The primary differences between domestic wuai and Bencharong are Bencharong’s different colour palette (particularly turquoise), which catered to Thai tastes, its lack of underglaze blue, and its enamel, which was more thickly applied.Bencharong enamels also cover the entire surface of the body, displaying no white porcelain, unlike many of their domestic Chinese counterparts.

Bencharong’s production history is difficult to reconstruct, as no commission records remain. However, recent excavations at Jingdezhen have revealed decorated Bencharong sherds, suggesting that Bencharong wares were both fired and decorated at Jingdezhen, during a period when some export wares were only fired at Jingdezhen and decorated after export.

Closeup of a wucai famille verte dish on display at the Holburne Museum. Both familie verte and Bencharong emply the same porcelain techniques.

Dating and Uses

One useful technique to date Bencharong objects is by palette. Objects such as the one below (currently on display at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin) can be dated to the eighteenth century because nineteenth- century pieces often heavily feature pink or gold, a technique called Lai Nam Thong.

This piece also minimizes use of purple and blue, meaning that it was unlikely produced after 1800. When examining an object, don’t forget to examine the interior, which can provide useful clues! For example, turquoise interiors are only found in earlier Bencharong wares. Precise dating is typically unreliable, as Bencharong styles did not always align with Thai reigns.

18th century Bencharong lidded bowl on display at the Humboldt Forum, featuring a Thai Buddhist figure called a thephanom.

Bencharong was often used as a dining ware, and therefore often came in matching sets.

Early Bencharong court wares also sometimes served as containers for cosmetics or medicine.

Initially, Bencharong was only produced for the Thai court, but high nineteenth-century demand necessitated expanded production for Thai nobility and merchants.

In the nineteenth century, King Rama II so admired Bencharong that he attempted to produce copies himself, as he was an amateur artist!

Visual Characteristics

Bencharong decorations often reflect traditional artistic tastes across Thai media. Bencharong’s most common motifs include geometric patterns, Buddhist or Hindu iconography, mythic or literary creatures, and Thai flora and fauna.

The entire surface of the Buddhist lidded bowl at the Humboldt Forum is covered with polychrome enamels in red, navy, turquoise, white, yellow, and green, with floral bands and motifs surrounding Buddhist figures. These bands typically frame primary motifs and are either plain or subtly decorated.

The various floral patterns, particularly the yellow stem pattern at the top of the bowl, are commonly found in Buddhist Bencharong wares. The red band near the bottom of the bowl and repeated throughout the lid is a lai kruay cherng pattern (a funnel motif) depicting repeating tri-lobed flowers.

Given Buddhism’s predominance in Thailand, many Bencharong wares depict scenes specific to Thai Theravada Buddhism. This scene takes place in the Himaphan forest, a lower Buddhist heaven. At the center of the primary scene sits a thephanom on a red medallion shaped like a lotus petal, with his hands in anjali mudra.

The thephanom is a minor celestial being in Thai Theravada Buddhism, often mistaken by contemporary viewers for a Buddha. He wears jewellery and an ornate Thai headdress.

Although he is featured alone here, he is often surrounded by norasinghs, Thai Buddhist semi-deities who flank the thephanom and can be identified by their human upper body and lion/ deer mixture lower body.

Collecting Bencharong

Bencharong remains a popular form in museums and in private collections throughout the world, with a demand for a contemporary reproduction market in Thailand. Taking your Bencharong wares to a valuer may help you determine whether your objects are antiques or are contemporary reproductions.

Bencharong reveals a rich history of trade, religious activity at Thailand’s royal court, and upper-class desires to emulate royal tastes.

Further academic examination of the history of Bencharong may result in a better understanding of China’s historical relationship with Thailand, religious and secular imagery in Early-Bangkok Period art, merchant trade culture, and the upper class’ relationship with the royal Thai court.

Meanwhile, there is plenty Bencharong for us to enjoy in public collections, such as the Humboldt Forum, the V&A, and the British Museum!

Originally from San Francisco, California, Ashley Innes (née Crawford) is an experienced Asian art valuer and provenance researcher. Her specialties include ceramics, Buddhist antiques, Indian miniature paintings, Southeast Asian art, and musical instruments.