From my experience in the UK Art Market the rise of interest from Chinese buyers has been enormous. For the first part of my career I worked in the European works of art and Asian Art salerooms of Christie’s South Kensington during the late 1990’s. The supply of available material for sale meant that every other week we could sell Chinese and Japanese works of art and porcelain. Very few clients were from the Asian countries, with most being drawn from the London and European trade. There was no internet and most buyers were reliant on catalogues, being present to bid or telephone bidding to buy at auction.

The current market is completely different. The availability of the internet to view sales, the use of agents for buyers in China and the global nature of the Art business has completely changed the market, with Chinese buyers coming to London especially in November to view and buy at sales and via the trade during Asian Art week. Regional salerooms have as much power to sell high value works of Chinese Art, as Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams. Regional auctioneers, while retaining their business independence, have worked together with the common interest to service and support the rise in demand for services to Chinese buyers.

The most valuable and saleable objects that are sold in the trade and via auction are those that exhibit rarity and a fine provenance. Previous ownership from a distinguished family, history and proof of trade via prestigious dealers all confirm on an object, a proof of history and by virtue of these qualities value.

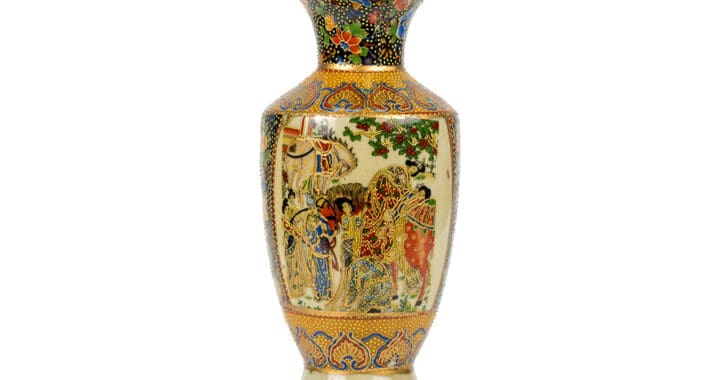

At Rosebery’s Fine art auctioneers in July 2020, a rare pair of Chinese porcelain wall or sedan chair vases, from the reign of the Emperor Qianlong were sold for £324,500 including buyer’s premium. They were consigned from a private collection in the UK, and decorated in what were termed as yangcai or “foreign colours” because of the pink famille rose grounds, which came to the knowledge of Chinese craftsmen from the influence of European missionaries and craftsmen who were in China. The Emperor Qianlong was a connoisseur of porcelain and ordered his craftsmen at the Imperial porcelain works in Jingdezhen to design a vase for a sedan chair for flowers. He is known to have written poetry, some of which appears on these vases, and those sold in the past.

The Imperial poem inscribed on the offered pair of vases, titled ‘The Hanging Bottle’, is documented in The Complete Library of the Four Treasures. The Qianlong emperor composed this poem in 1758, the 23rd year of his reign, to express his delight upon viewing a sedan vase filled with fresh flowers hanging in his sedan chair on the way to a hunting trip. There are 320 Qianlong wall vases recorded in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing and about 138 of them are inscribed with poems by the emperor. There are thirteen wall vases in varying glazes and forms on the wall of The Hall of Three Rarities, the emperor’s special study in the Hall of Mental Cultivation in the Forbidden City.

The value achieved at auction was influenced by the colour of the decoration, the fact that they were a pair and that they had direct connection to the Emperor Qianlong. A Chinese agent eventually secured the winning bid.

A pair of Chinese porcelain wall or sedan chair vases, from the reign of the Emperor Qianlong were sold for £324,500 in July 2020. Image courtesy of Rosebery’s fine Art auctioneers.

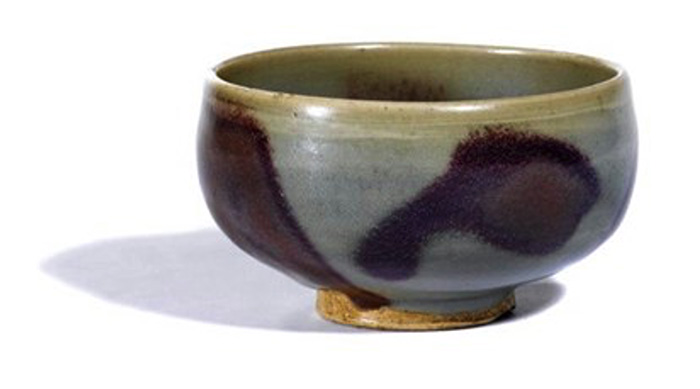

Scholars have collected a wide range of different ceramic wares from China over the centuries. Of my favourite are the wares decorated in single colours or variations of this theme. One type of ware is called Jun ware and dates from the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Ceramics were produced in Junzhou Prefecture (today’s Yuzhou) in Henan province, found in the middle of China. Ceramic production lasted there from the Song (960-1279) to the Ming (1368-1644) dynasty and is usually typified a thick almost custard like pale purple glaze, with splashes of a deeper purple on the surface. These wares, while not greatly prized, were still revered in the Ming dynasty and continue to achieve high values at auction.

Chinese Jun bowl produced during the Song Dynasty. Image courtesy of Woolley and Wallis.

This Chinese Jun bowl was sold on the 21st May 2014 for £26,000 and is typical of the wares produced during the Song Dynasty, but was attributed to a rival faction of the same period, the Jin. It is typical of the type of bowl made of the period with the thick pale lavender coloured glaze over laid with abstract cloud like large purple splashes.

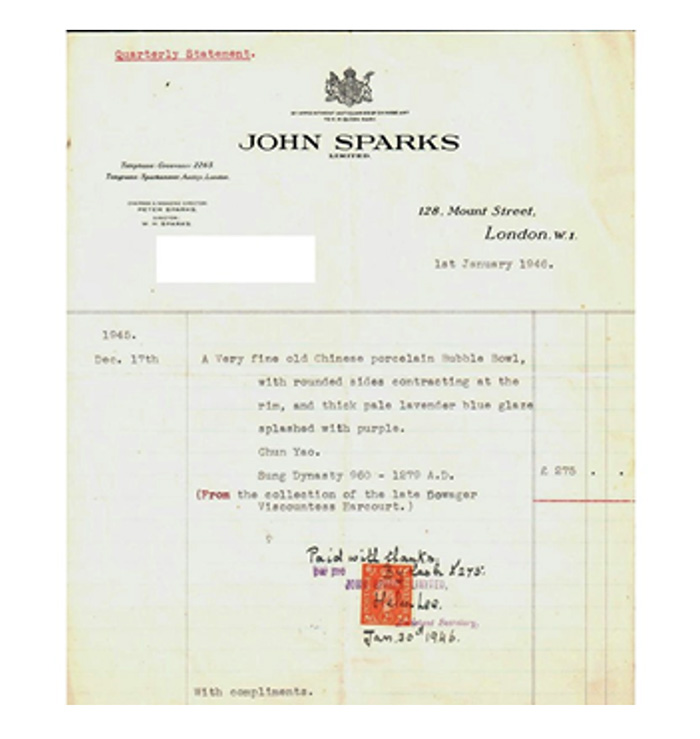

Invoice for the Chinese Jun bowl dated 1946, from John Sparks, London. Images courtesy of Woolley and Wallis.

Of importance to the piece was the provenance from the dealership of John Spark’s Ltd, a prominent London dealer, whose receipt was sold with the piece, dated the 1st January 1946 and the former owner, the late Dowager Viscountess Harcourt. Of equal importance is the fact that a similar form of bowl is found in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.