Pablo Picasso died on April 8, 1973, which makes 2023 the 50th anniversary of his death. Incidentally it is also exactly 50 years since I started my career in the Art world at Thomas Agnew in Old Bond Street, where I first had the privilege of handling Picasso’s work.

Pablo Picasso died on April 8, 1973, which makes 2023 the 50th anniversary of his death. Incidentally it is also exactly 50 years since I started my career in the Art world at Thomas Agnew in Old Bond Street, where I first had the privilege of handling Picasso’s work.

Picasso was very much a polymath, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and all round genius who was always making art and is widely regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. He was a pioneer of the Cubist movement and his groundbreaking works continue to captivate audiences around the world. On the 50th anniversary of his death, it is a time to reflect on his legacy and contribution to art and the world. Picasso’s works can be seen in many of the world’s most famous museums and galleries, and continue to inspire new generations of artists.

His impact on the art world continues to be felt today and many very well known and highly regarded artists have been influenced by Picasso’s groundbreaking style and innovative techniques, including:

- Georges Braque: A close collaborator of Picasso’s during the development of Cubism, Braque was deeply influenced by Picasso’s work and the two artists had a major impact on each other’s style.

- Juan Gris: A Spanish painter and sculptor, Gris was also a key figure in the Cubist movement and was heavily influenced by Picasso’s work.

- Henri Matisse: While Matisse is known for his distinctive style, he was also influenced by Picasso’s use of colour and form, and the two artists maintained a close friendship throughout their careers.

- Joan Miró: A Spanish surrealist artist, Miró was inspired by Picasso’s bold experimentation with form and colour, and the two artists were close friends.

- Frida Kahlo: While Kahlo is primarily known for her distinctive self-portraits, she was also influenced by Picasso’s innovative approach to portraiture and the two artists shared a close friendship.

Place and culture was a great influence on Picasso and he lived in many different places throughout his life, some of the most significant include;

- Barcelona, Spain: Picasso was born in Malaga, Spain, but spent much of his childhood and early artistic career in Barcelona.

- Paris, France: In 1904, Picasso moved to Paris, which was then very much seen as the centre of the art world, and he lived and worked there for many years. During this time, he was associated with the Cubist movement and developed many of his most famous works.

- Cannes and Antibes, France: After World War II, Picasso spent much of his time in the south of France, living and working in the towns of Cannes and Antibes.

- Mougins, France: In 1961, Picasso moved to the small town of Mougins in the south of France, where he lived until his death in 1973.

Pablo Picasso’s work can be divided into several distinct periods, each characterised by its own dominant colour palette. Some of the most well-known colour periods of Picasso’s work are:

- The Blue Period (1901-1904): During this period, Picasso’s works were primarily painted in shades of blue and blue-green, with themes of poverty, loneliness, and sadness.

- The Rose Period (1904-1906): This period saw a shift to warmer, pinkish hues, and the introduction of more playful themes such as circus performers and harlequins.

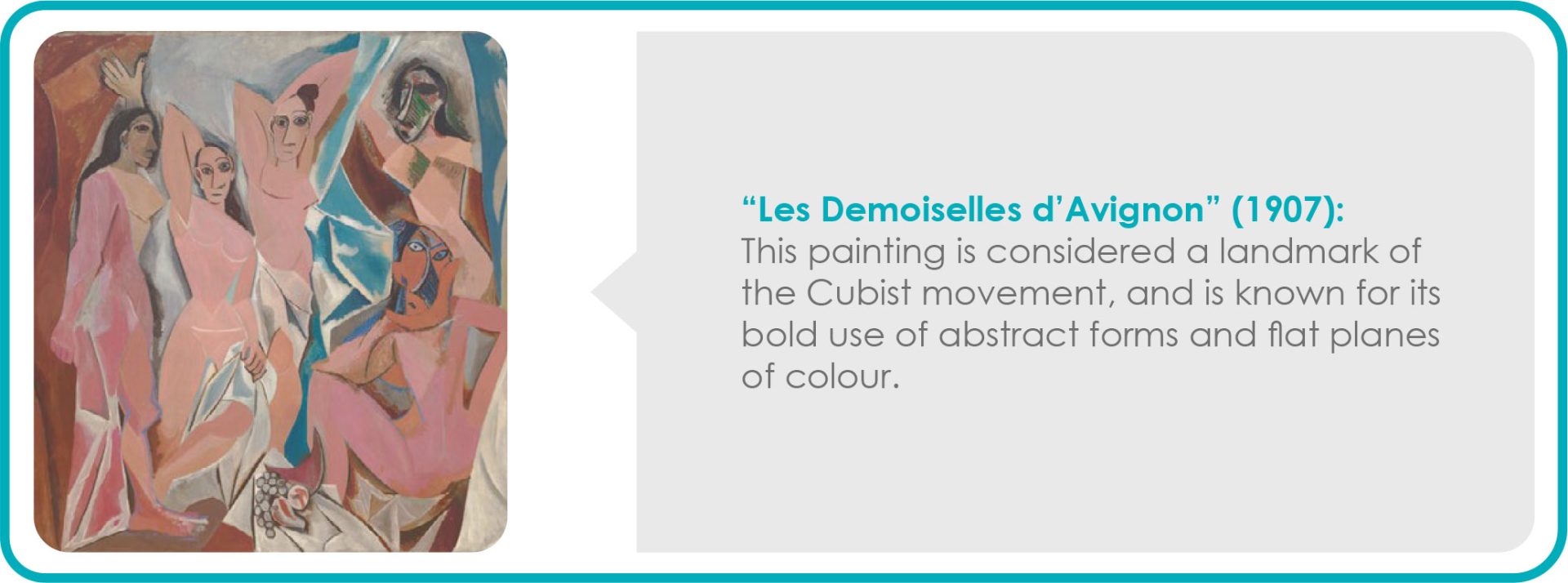

- The African-Influenced Period (1907-1909): In this period, Picasso was influenced by African art and started incorporating abstract and geometric shapes into his works, resulting in a bold and experimental style.

- The Analytical Cubism Period (1909-1912): During this period, Picasso and Georges Braque developed the style of Analytical Cubism, characterised by fragmented and abstracted forms.

- The Synthetic Cubism Period (1912-1919): This period saw a further simplification of form, with the use of cut-out paper and printed materials incorporated into the paintings.

While these are some of the most significant colour periods of Picasso’s work, it is important to note that Picasso was always experimenting and evolving, and his style changed frequently throughout his very long career of almost unceasing endeavour to make art.

Some of his most well-known works include:

There are dozens of exhibitions taking place around the globe all marking this major anniversary each taking a differing approach, the link below gives you a taste of their variety dates and locations, hopefully you will be able to get to see at least one of them to witness for yourself the energy and sheer creative genius of Pablo Picasso.

Click here to read more about the dozens of exhibitions worldwide marking the 50th anniversary of Pscasso’s death.