‘Never judge a book by its cover’ – that’s what we’re always told. We never know what’s really happening beneath someone’s public persona – and none more so than with famous actors or musicians, who we think we know so well through their film or music. But this fame and celebrity can often be misleading as many of the most famous celebrities have kept a secret from their fans – the secret being that they are artists (painters, photographers, sculptors) independent of their day jobs. In fact, in some case, the celebrities identify more as visual artists than their more famous personas!

Below are 10 celebrities who might surprise you with their double life!

David Bowie

David Bowie was undoubtedly one of the greatest creative forces of the 20th century, known for his ability to effortlessly reinvent himself over and over. It’s not surprising, therefore, that his creativity was also multifaceted and that he was a practicing visual artist for as long as he was a musician. Until 1994, however this side of his work remained unknown to the public. For the glam icon, painting was an essential part of the musical process.

As he explained during a conversation with The New York Times in 1998: ‘I’ll combine sounds that are kind of unusual, and then I’m not quite sure where the text should fall in the music,’ he explained, ‘Or I’m not sure what the sound conjures up for me. So then I’ll go and try and draw or paint the sound of the music. And often, a landscape will produce itself.’

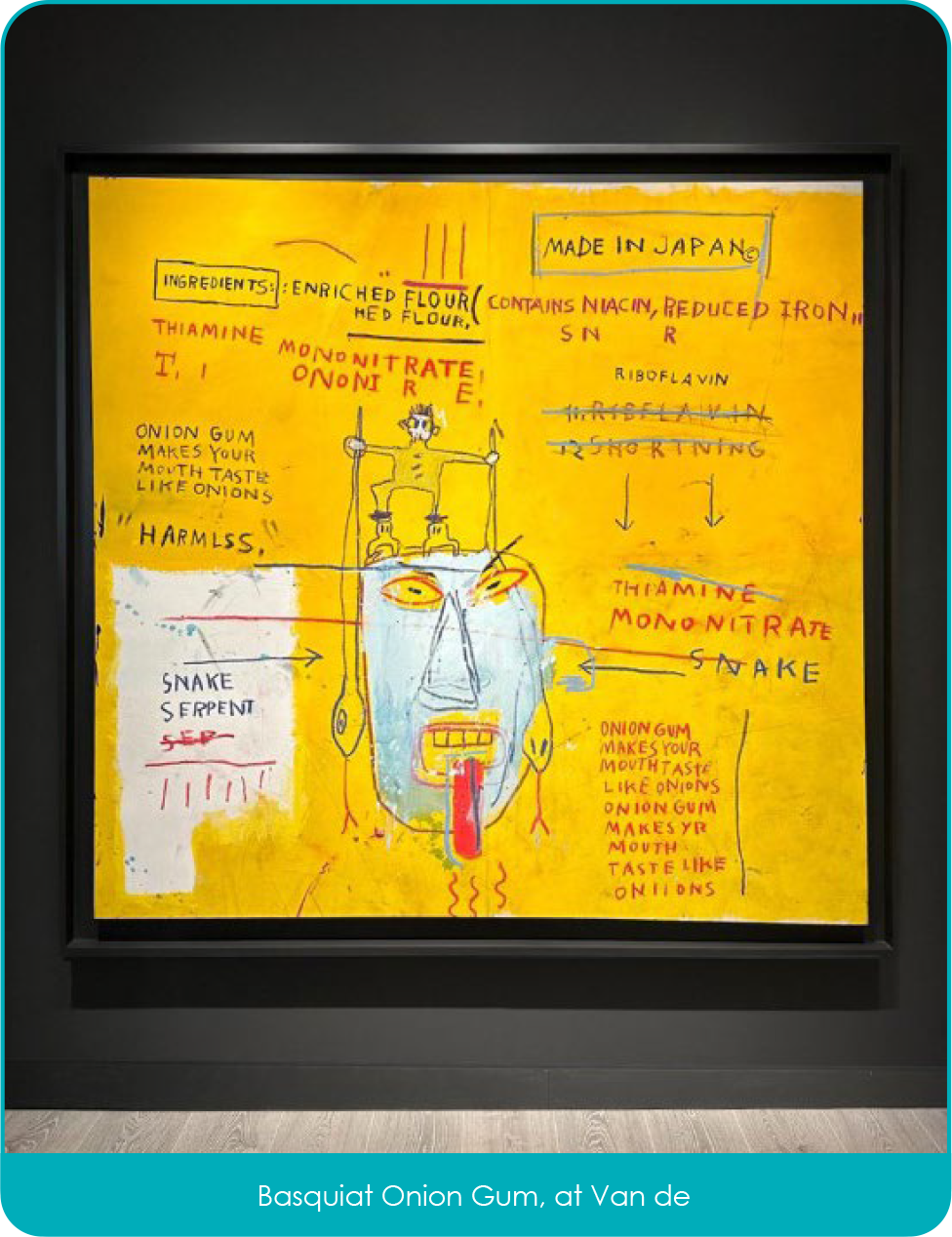

Bowie was also a devoted art collector, and he had a close affinity with the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

‘I feel the very moment of his brush or crayon touching the canvas, there is a burning immediacy to his ever-evaporating decisions that fires the imagination ten or fifteen years on, as freshly molten as the day they were poured onto the canvas. It comes as no surprise to learn that he had a not-so-hidden ambition to be a rock musician. His work relates to rock in ways that very few other visual artists get near.’

Jim Carrey

Jim Carrey’s comedy and movie background is already legendary, but most people don’t realise that he is also an artist with a number of public exhibitions under his belt! Carrey has been drawing and painting since childhood, and not surprisingly considering his sharp wit and edgy sense of humour, his art is highly political and satirical; criticising and digging into the woes of modern-day America. Carrey is both a painter, sculptor and print maker.

In common with many of his actor / artist contemporaries, Carrey uses his art to ground and settle him, to enable him to switch off. As he says, ‘When I sculpt and paint is when I feel the most present and in harmony with the environment; as if all time has been suspended, all gravity disappears.’

Bob Dylan

As if he wasn’t content with being one of the most iconic musicians of modern times, Bob Dylan has also established himself as a painter and sculptor of international acclaim. The ‘Blowin In The Wind’ singer has been given pretty much every award you can think of, including the Pulitzer Prize, The Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Nobel Prize for Literature, an Oscar, and the National Medal of Arts.

Dylan dates the beginning of his work as a visual artist to the early 1960s. A few drawings reached the public gaze with album covers like Music from Big Pink (1968) and Self Portrait (1970), but it was not until 1974, that Dylan started to take his art serious. He spent two months studying art with Ashcan School tutor Norman Raeben, who philosophised the importance of ‘perceptual honesty’ – painting life as it as seen, not imagined. Dylan says of this time: ‘He put my mind and my hand and my eye together, in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt.’

The inspiration behind Dylan’s art are travels – the cities and towns he visits appear on the canvases he produces, interpreted in the brightly graphic, expressionistic style he has made his own. He says his art is about the instant moment of a place, person and time, and it has found enormous appeal with audiences worldwide. The combination of the Dylan name and his accessible imagery is a winning combination.

Dylan’s first major retrospective, Retrospectum, opened in the Modern Art Museum Shanghai in 2019/20 and was visited by over 100,000 people in the first three months. He is now represented by a number of heavy hitting international galleries such as Halcyon and Opera Galleries.

Dennis Hopper

From Hell’s Angels and hippies to the streets of Harlem, Dennis Hopper’s photography powerfully captures American culture and life in the 1960s, a decade of progress, violence and enormous upheaval.

Hopper carved out a place in Hollywood history, with roles in classic films like Apocalypse Now, Blue Velvet, True Romance and Easy Rider. He is less well known, though no less respected, for his work as a photographer.

In 2014 Hopper’s photographic work was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy in London – entitled: Dennis Hopper – The Lost Album. This exhibition brought together over 400 images, taken during one of the most creative periods of his life in the 1960s.

This was a decade of huge social and political change, and Hopper was at the eye of the storm. With his camera trained on the world around him he captured Hell’s Angels and hippies, the street life of Harlem, the Civil Rights movement and the urban landscapes of East and West coast America. He also shot some of the biggest stars of the time from the worlds of art, fashion and music, from Andy Warhol to Paul Newman.

Together, these images are a fascinating personal diary of one of the great countercultural figures of the period and a vivid portrait of 1960s America.

Lucy Liu

More commonly known for her roles in the movies Kill Bill and Charlie’s Angels, as well as the TV show Elementary, the American actress Lucy Liu is also a very talented abstract artist. She has painted for years, under the pseudonym Yu Ling.

Liu’s interest in art began at the age of fifteen, when she started experimenting with collage and photography at Stuyvesant High School in New York City. She graduated from the University of Michigan in 1990 with a B.A. degree in Asian Languages and Culture, before moving to Los Angeles to pursue her interest in acting. Her first solo exhibition, Unraveling, at Cast Iron Gallery in New York in 1993, was a photographic exhibition that earned her a grant to study at Beijing Normal University. Liu found this period in China to be extremely valuable, not only as an opportunity to learn more about her Chinese heritage, but also to expand her understanding of the symbolic potential of art. The trip became the subject of a body of work shown at her next one-person exhibition, Catapult, at Los Angeles’ Purple Gallery in 1997. Liu remained in Los Angeles for several years, during which time she continued to work in collage and photographic portraiture. She returned to New York City in 2004 and enrolled in painting classes at the New York Studio School from 2004-2007.

Ongoing conceptual concerns in Liu’s artwork have been the notions of security, salvation, and the long-term effects of personal relationships on our physical and emotional selves–themes that she addresses in painting, sculpture, collage, silkscreen, or the appropriation of discarded objects, which Liu recontextualizes in handmade constructions that function as reliquaries.

Her work has been featured in numerous gallery exhibitions and international art fairs, and is included in multiple private and corporate collections. Liu currently lives and works in New York City.

Paul McCartney

The Beatles were a true global phenomenon within contemporary culture – arguably the world’s most famous band, against who all other bands are measured. In addition to this, Paul McCartney is one of the most successful composers and performers of all time. He has written or co-written 32 songs that have reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, and as of 2009, had sales of 25.5 million RIAAcertified units in the United States.

For more than thirty years, alongside his music career, McCartney has been a committed painter, finding in his work both a respite from the world and another outlet for his drive to create. His paintings were a very private endeavour until 1999 when he decided to share his artwork with a public exhibition and a book titled ‘Paul McCartney Paintings.’ His work is now represented by a number of galleries internationally.

McCartney’s works are full of intense colour and life – his paintings reveal McCartney’s tremendously positive spirit as well as a visual sophistication. The combination of techniques, such as scratching, wiping and applying paint directly from the tube, clearly documents on the one hand the artistic process as it takes place on the canvas but creates on the other hand the illusion of objective realism, with the elements air, water and earth. Faces abound in his paintings and humour plays against a more sombre imagery, while his landscapes radiate a sense of place.

Joni Mitchell

Think of Joni Mitchell and think primarily of her incredible career as a singer, songwriter and musical innovator, whose songs have helped define an era and generation. She has received many accolades, including nine Grammy Awards, and has released 19 studio albums. Much less has been written of her life as a painter. It might surprise fans to hear that Joni has always considered herself to be a painter first and a musician second!

Joni started painted extensively in the ’60s and has never stopped since, except for a few brief, ill-advised forays into photography in the 1980s. The ’60s paintings are almost exclusively portraits of those around her, often drawn from reproductions of sketchpad drawings made on the road or in recording studios. Those around her are mostly men: some of them lovers (Graham Nash, David Crosby), some friends and professional barometers (Neil Young, Bob Dylan), but for their cheery, empty impersonality, they might as well be strangers.

Stevie Nicks

Stevie Nicks, the evocative lead singer of the folk rock band Fleetwood Mac, has painted throughout her long career, but yet she says she doesn’t really think of herself as a painter. This modesty belies a body of work which almost perfectly reflects the essence of her music, and evokes the bucolic feel of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Her paintings are at once folkish and deeply biblical.

‘They’re all angels,’ she said of her art. ‘I only draw angels. I started to draw when my best friend got Leukemia. And that’s what she’s left me. And so I know she’s really excited now because it has finally, after the last 9 years, come to fruition, and people have finally started appreciating it. But I never drew a thing before she got sick.’

Sylvester Stallone

Sylvester Stallone has been an icon in the film world for decades, best known for writing and starring in the blockbuster movie franchise Rocky. But few of his fans realise that he has been painting for almost as long as he has acted – nearly 50 years.

Stallone’s work has evolved over the decades, with later canvases veering towards abstract forms and a reduced colour palette of black, white, and red. Stallone cites the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francis Bacon, and Kasimir Malevich as his key influences, as well as Andy Warhol, for whom he famously posed in a series of photographic portraits in the 1980s. A prolific screenwriter, he often used art to help conceptualize his characters; including his 1970s painting Finding Rocky served as a means of entry into his character’s mindset. Stallone’s works have been featured in retrospective museum exhibitions in St. Petersburg, Russia, and Nice, France.

Who would have thought it, but this quintessential bad boy of rock ‘n roll has consistently found solace in art and has painted throughout his wild days in the Rolling Stones. Ronnie Wood says: ‘There is no kind of therapy like the one you have from starting a picture and then seeing it through to the end.’

Having received formal art training at Ealing College of Art, Ronnie has been a prolific painter since his teens. He has described painting as being like therapy and would create portraits of figures he admired. Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix and fellow band member Mick Jagger are just a few of those he has painted, along with other musicians, friends and family.

Varying his medium depending on the mood he wishes to evoke, Ronnie creates his original pieces in charcoals, oils, watercolours, spray paints, oil pastels and acrylics. His subjects range from band members and musicians he admires to close friends and self-portraits.

For Ronnie, music and art have always gone hand-in-hand, and the intensity that he brings to the guitar translates onto canvas and paper with rhythmic line and vibrant colour. Ronnie’s paintings are a record of his many talents and loves. One of the things he most enjoys is to paint the views from his farm in County Kildare Ireland and the horses he keeps in stables there, allowing him time to take time out from both the media attention that follows him everywhere and also work on his future projects, both with the Rolling Stones and other musicians, in a more secluded atmosphere.

‘I apply musical theory to my art. I build artworks in much the same way as studio overdubs, the more defined ones are things that stand out in the mix.’