I have been involved in Modern British painting and sculpture since 1987 when I took charge of Christie’s Modern British department. This brought me into direct contact with the artists themselves, their families, friends and collectors, which I found totally absorbing and fascinating. My fate was sealed, and I think I became a Modern British ‘Lifer’ in 1988 when we held the Camden Town Group exhibition. However, little did I know back then just how large a part Lowry would play in my working life over the next 32 years.

‘The Village Street’ appeared in the Christie’s Review of the Year for the 1964-65 season having been sold for a then record price of 1,600 Guineas

I think it’s fair to say that L S Lowry is probably one of the best known 20th century painters in the UK, with his work being more easily recognisable to British people than many other national or even international artists. This wide recognition and easy acceptance have led to a healthy and consistently strong level of interest from private collectors over the last 60 or more years.

For the first-time art collector, Lowry’s signature pieces are immediately engaging and have a broad appeal. Typically, a first and second Lowry purchase would both be signature pictures, after which would follow less obvious works, such as a minimalist sea piece or a dreamlike, haunting, empty landscape. This interest in collecting a single artist led to the formation of some great collections, many of which I have had the privilege of either helping put together and or selling over the years.

Critical and financial success for Lowry, like so much in his life, came late. Although born in 1887, his first London exhibition at the Lefevre gallery was not until Autumn 1939, then again in 1943 and the third in 1945, when Britain had other things on its mind.

‘Northern Race Meeting’ which achieved £5,296,000 in 2018

Lowry served the War out as a Fire Warden in Manchester and when life and exhibitions began again at Lefevre in the 50’s, buying Lowry pictures suddenly became very fashionable and fun and his exhibitions were sell-outs. So strong was the interest that at one point in the early 60’s Lowry’s prices at auction exceeded his then current gallery prices. As if to illustrate this, an article featuring a 1935 picture called ‘The Village Street’ (pictured) appeared in the Christie’s Review of the Year for the 1964-65 season having been sold for a then record price of 1,600 Guineas.

If the sixties marked the beginning for Lowry acquisitions and collections, then March 1995 and the Rev. Geoffrey Bennett collection sale at Christie’s, marked the beginning of a series of collection sales at auction. Bennett was followed by the Frederick Forsyth collection, 2002, Laurence Ives, 2004, Lord Forte, 2011 and the Thompson collection in 2014. All of these single owner, single artist sales helped to expand the market and to increase the awareness of Lowry and also spawned new collectors many of whom I have got to know well.

‘The Football Match’ sold for £5,641,00 in 2011

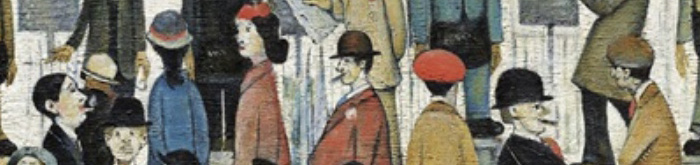

Although there haven’t been any significant collection sales since the Thompson sale in 2014, Lowry prices and interest have remained strong with top prices still being achieved for signature pictures such as Northern Race Meeting (pictured) in 2018, which achieved £5,296,000.

Equally many records still stand from 2011-2014 such as The Football Match (pictured) in 2011at £5,641,00 and Piccadilly Circus (pictured) at £5,122,000 in 2014.

Lowry painted and drew continuously throughout his long and very productive life, so happily there are still many new works out there still to be discovered. I have been fortunate enough to have seen hundreds of works by Lowry over the years through my work with collectors and involvement with the Lowry collection in Salford and I look forward to seeing many more…

‘Piccadilly Circus’ achieved £5,122,000 in 2014