£5,000 to buy art – sounds wonderful, doesn’t it? It is certainly a decent chunk of change to play with – large enough to focus the mind and to open the possibility of buying something a little bit more special than a decorative wall filler. Conversely, the moment one starts looking at works in a slightly higher price bracket, and by artists who have more pedigree, suddenly £5,000 doesn’t seem that much at all! A strategy is, therefore, needed if the canny buyer is to maximise their buying power.

For me, if I had £5,000 to spend on one artwork, I would adopt a twofold approach – firstly I would look to buy as good a work on paper as I could find by an artist whose work I loved, but whose paintings are out of my reach. Secondly, in order to maximise my buying power, I would concentrate my search entirely on the auction market rather than buying from a retail gallery. Buying from auction can take a little more time, and it needs a little more research by the collector, but it often allows one to buy works considerably cheaper than retail level. As a famous supermarket says – every little helps!

The artist I would buy with my £5,000 is an artist who I think is significantly undervalued in the current market, both in terms of his talent as well as in comparison to the values many of his contemporaries achieve. Keith Vaughan is a relatively overlooked Modern British artist who was born in 1912 at Selsey Bill in Sussex. He was a self-taught artist with no formal instruction in art, yet he went onto forge a highly individualist and distinctive career which has until fairly recently has been overshadowed by the giants of his generation – Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Terry Frost, Ivan Hitchens etc.

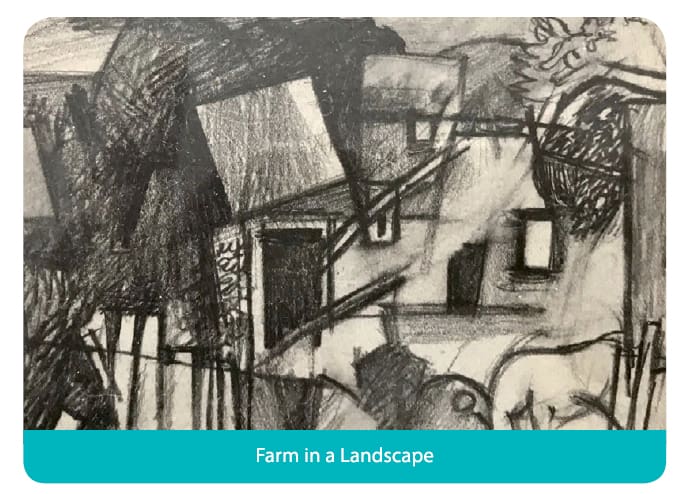

Vaughan started his career as a commercial artist when he was apprenticed at the Lintas advertising agency, from which he gained an understanding of composition and form – both essential skills in commercial art. From 1939, after he left Lintas, Vaughan became a full-time artist. With the outbreak of World War II, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector and joined the St John Ambulance; in 1941 he was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps.

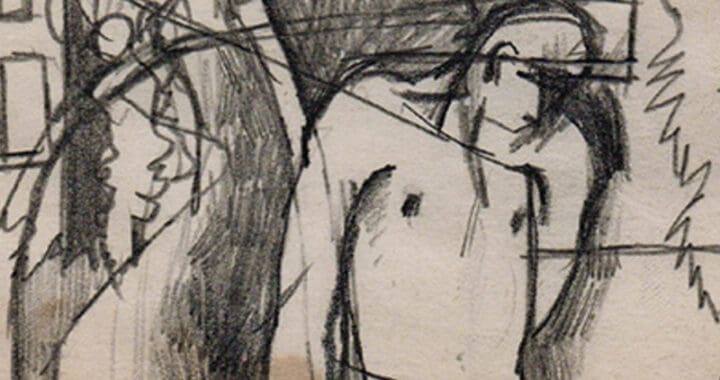

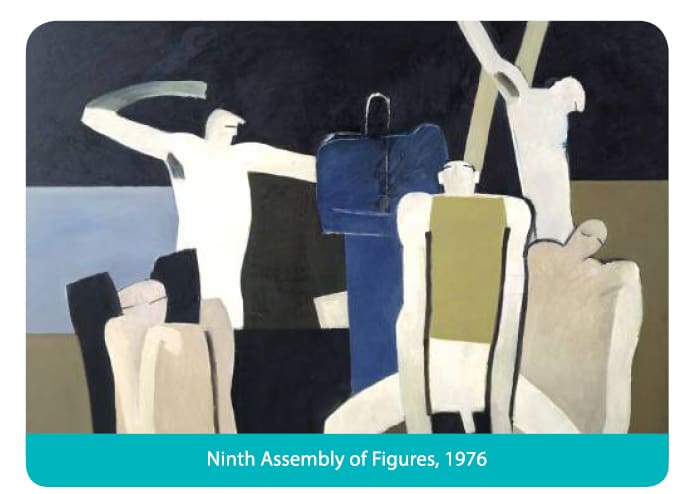

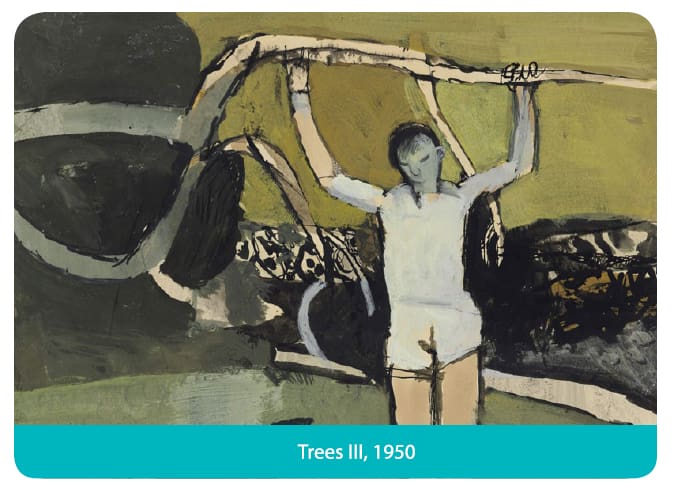

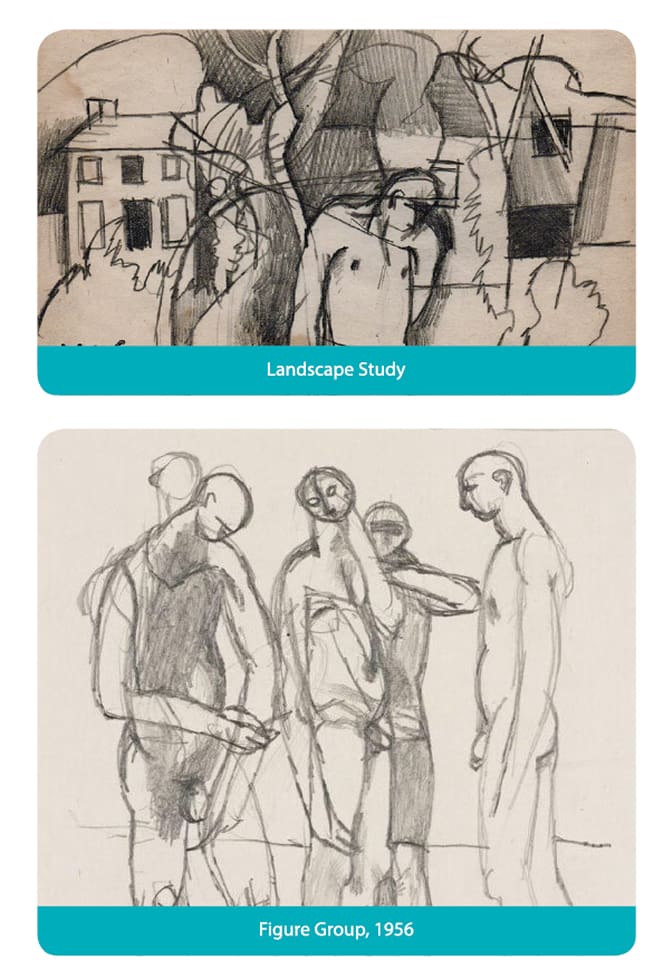

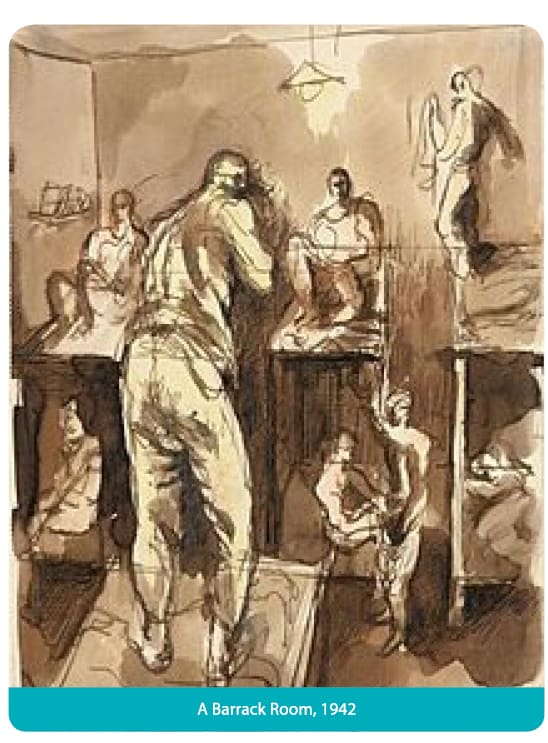

During the war Vaughan formed friendships with the painters Graham Sutherland and John Minton, with whom after demobilisation in 1946 he shared premises. Through these contacts he formed part of the neo-romantic circle of the immediate post-war period. However, Vaughan rapidly developed an idiosyncratic style which moved him away from the Neo-Romantics. Concentrating on studies of male figures, his works became increasingly abstract.

Vaughan worked as an art teacher at the Camberwell College of Arts, the Central School of Art and later at the Slade School.

Throughout his life, Vaughan’s struggled with his own internal demons. Keith Vaughan was a gay man living in a time when homosexuality was illegal and actively frowned upon by Society. His struggle with his sexuality is reflected throughout his work and in his source of subject matter. Studies of figures and male nudes feature heavily in his work, although they are simplified and abstracted showing the influence of both international Modernism, Cubism his love of ballet and dance. Vaughan suffered from habitual depression and alcoholism, which eventually resulted in his suicide in 1977.

One might be forgiven for thinking that in light of all this Vaughan’s work would be negative and dour, however, this is wrong. As is often the case, personal struggles can produce works of great sensitivity and subtly. Vaughan’s work has a graphic quality that is softened by the use of a very sophisticated colour palette. They are very beautiful, elegant images.

The commercial art market has begun to reflect the increasing interest in, and appreciation of Vaughan’s work, with good examples now regularly achieving six figure sums at the auction. His works are also appearing more frequently at high end art fairs, where wall space has a commercial value, and a dealer’s decision to show a Vaughan instead of another artist is a calculated strategy, and one that reflects growing demand.

And yet, even with this increased visibility Keith Vaughan’s work is still undervalued in relation to many of his contemporaries, and it represents significant investment potential. His drawings in particular are surprisingly accessible financially and it is entirely possible to buy lovely pencil or pen and ink studies for a thousand or two, sometimes less; and more important, finished watercolours and gouaches can be bought within our £5,000 budget at auction.

How long this relative accessibility will last, I cannot say, but in my opinion now is definitely the time to buy Keith Vaughan’s work if like it and respond to it. Clearly, as always, liking an artist’s work is the primary reason for buying it, but it’s always nice to have a healthy upside too.

Ben is an established contemporary art specialist. He began his career working in the Old Master and 20th Century markets before moving into the contemporary market. He has over 20 years’ experience working in the UK and international art markets.