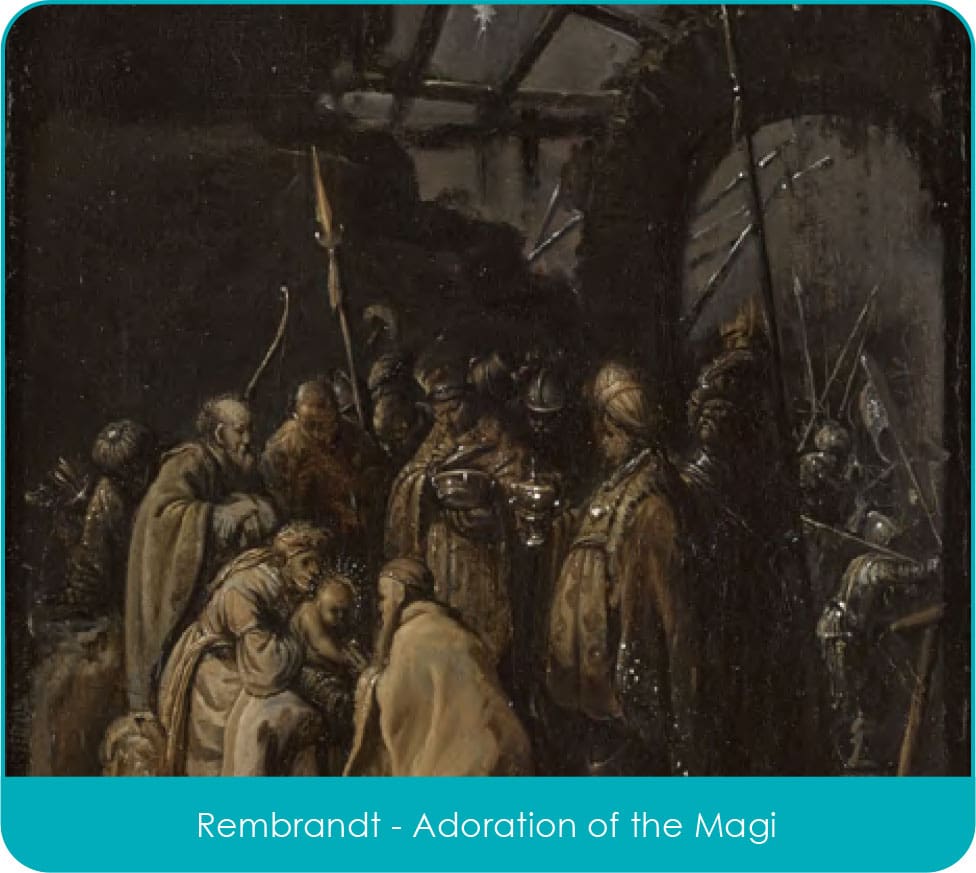

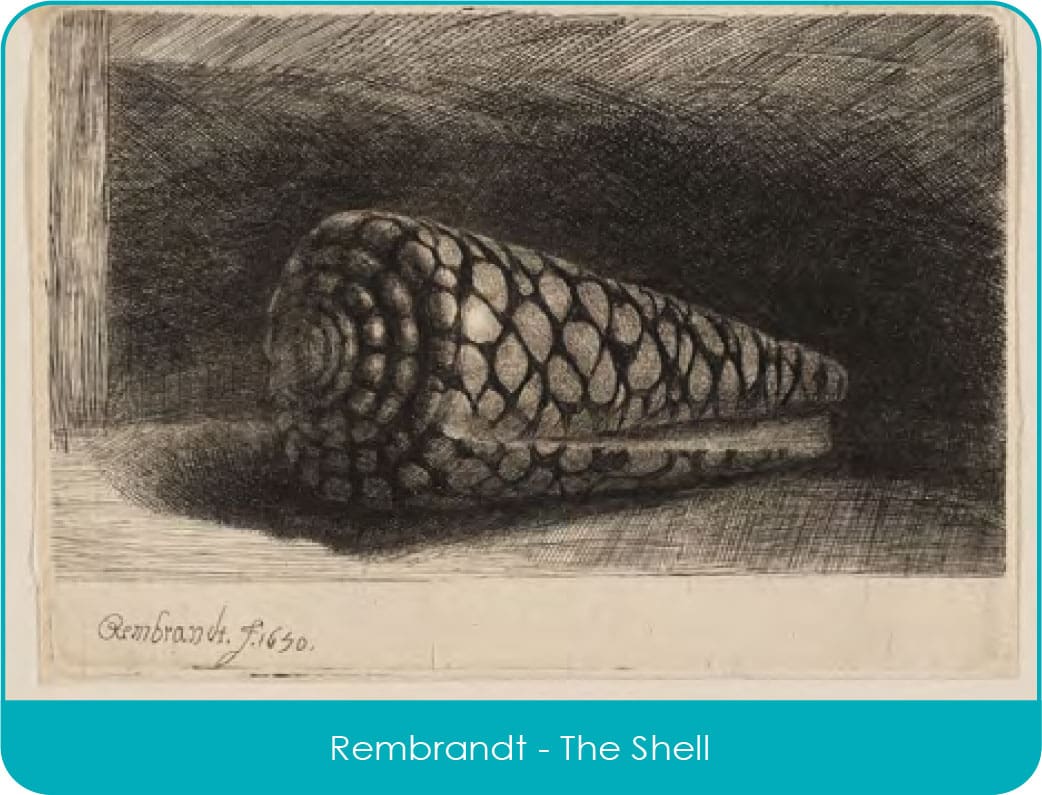

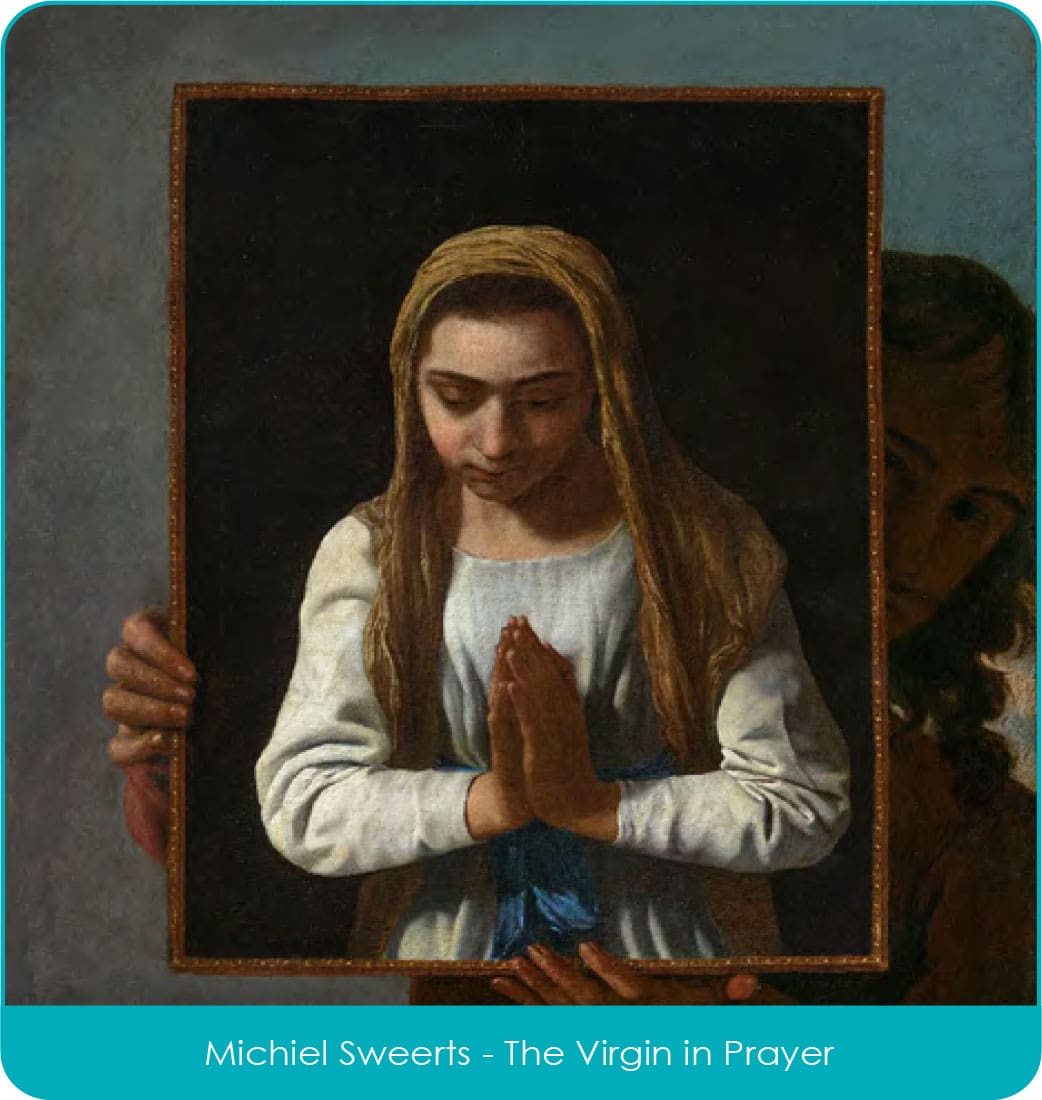

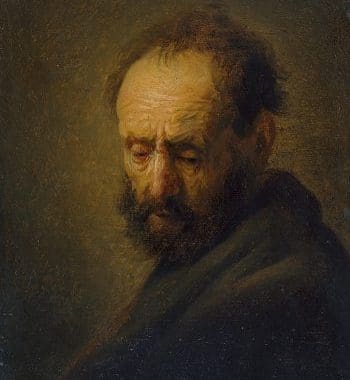

The current exhibition at H’Art Museum in Amsterdam (formerly known as the Hermitage Amsterdam, before links with the St Petersburg Institution were severed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) is “From Rembrandt to Vermeer: Masterpieces from the Leiden Collection”. As the name would suggest, the paintings are mostly by artists from Leiden such as, Jan Steen and Gabriel Metsu and Leiden is where Rembrandt and Jan Lievens shared a studio before moving to Amsterdam.

This illustrious collection has been assembled and is owned by my friend Tom Kaplan. Tom is the Chairman of Electrum Group, which specialises in precious metals. Despite being a New Yorker, he went to Oxford University and got a first in Modern History. He also gained a PhD for work on counter-insurgency in Malaya. He is a polymath. He has a passion for Rembrandt and his associates, which is only superseded by his love for big cats. In 2006 Tom co-founded Panthera, a charity devoted to “securing the future of the 40 species of wild cats and their critical role in the world’s ecosystems – securing their future and ours”, to quote their home page.

Among the treasures of the Leiden Collection on view in Amsterdam, is a superb drawing in chalks by Rembrandt of a young lion resting. It has been reported in the Art Newspaper and elsewhere, that Tom Kaplan will sell this great drawing sometime in 2026, with the proceeds going to benefit Panthera. It is expected to make an 8-figure sum and could even eclipse the world record for a work on paper, which was set in 2012, when the Head of a young Apostle by Raphael made £29.7M ($48M at the time).

Serena, my wife, and I, had the good fortune to spend 10 days as the guests of Tom in the Pantanal, a wetland in Brazil, the size of England, in the early autumn (their spring) of 2008 and see the work of Panthera in action. Tom had bought a large tract of farmland to provide a safe corridor for Jaguars to travel between two wildlife sanctuaries.

It’s worth remembering that in the 1950s and 60s, 25,000 Jaguar pelts made their way into the New York fur trade every year. The farm has 7000 head of cattle protected from predation by Jaguars, by being accompanied by Water Buffalo, which are extremely dangerous and in Brazil, produce the most disgusting Mozzarella known to man! There has been predation, nevertheless, over the four centuries that Europeans have had cattle in Brazil and this rich diet has caused the local population of Jaguars to increase vastly in size. A healthy male can weigh between 300 and 350 lbs, roughly the same as a Lioness, but with a much more powerful bite. Jaguars do not asphyxiate their prey, they crush their skulls. Jaguars in Guyana, by comparison, weigh a mere 80 to 120 lbs.

We had the further good fortune to be on the Cuiaba River, in the Pantanal, with fellow guest Steve Winter, who had just won World Wildlife Photographer of the year for his work on Snow Leopards, another of Tom’s protected species. One morning, after a relatively fruitless trip down the river, except for seeing a family of Giant Otters sharing fish with their youngsters, (adult Giant Otters are the same size as me) we bumped into Steve and he said he’d just seen a beautiful young Jaguar coming out of the shade of some trees onto open ground, because one of the boat drivers was throwing fish for him to eat. This practice has now been banned, as anything that distorts a wild animal’s natural behaviour, is not to be encouraged. Anyway, we hurried down river in our boat with Steve Winter directing us where to go. After 20 minutes at full throttle, we arrived at the steep bank where the Jaguar had been spotted, and he was still there! I got some memorable shots with my little Leica and Steve, whose camera took 10 frames a second took some rather better ones.

The show in Amsterdam, at the H’Art Museum, which exhibits 17 Rembrandt oil paintings, nearly half the total of those in private hands, and also has our cuddly lion on a leash, is on until August 24th 2025, when it heads for West Palm Beach, Florida. Try to get to see it if you can, as you may be seeing, not only a collection of Dutch 17th Century masterpieces, but also the most valuable drawing ever sold. We will be reporting what happens to the drawing at auction next year.