Lunar New Year, which begins on 10 February in 2024, is the largest festival in many East and Central Asian cultures. Lunar New Year typically falls on the second new moon following the winter solstice. In China, this festival is also called Chinese New Year or the Spring Festival. Each year highlights one of twelve animals in the Shengxiao, the Chinese Zodiac.

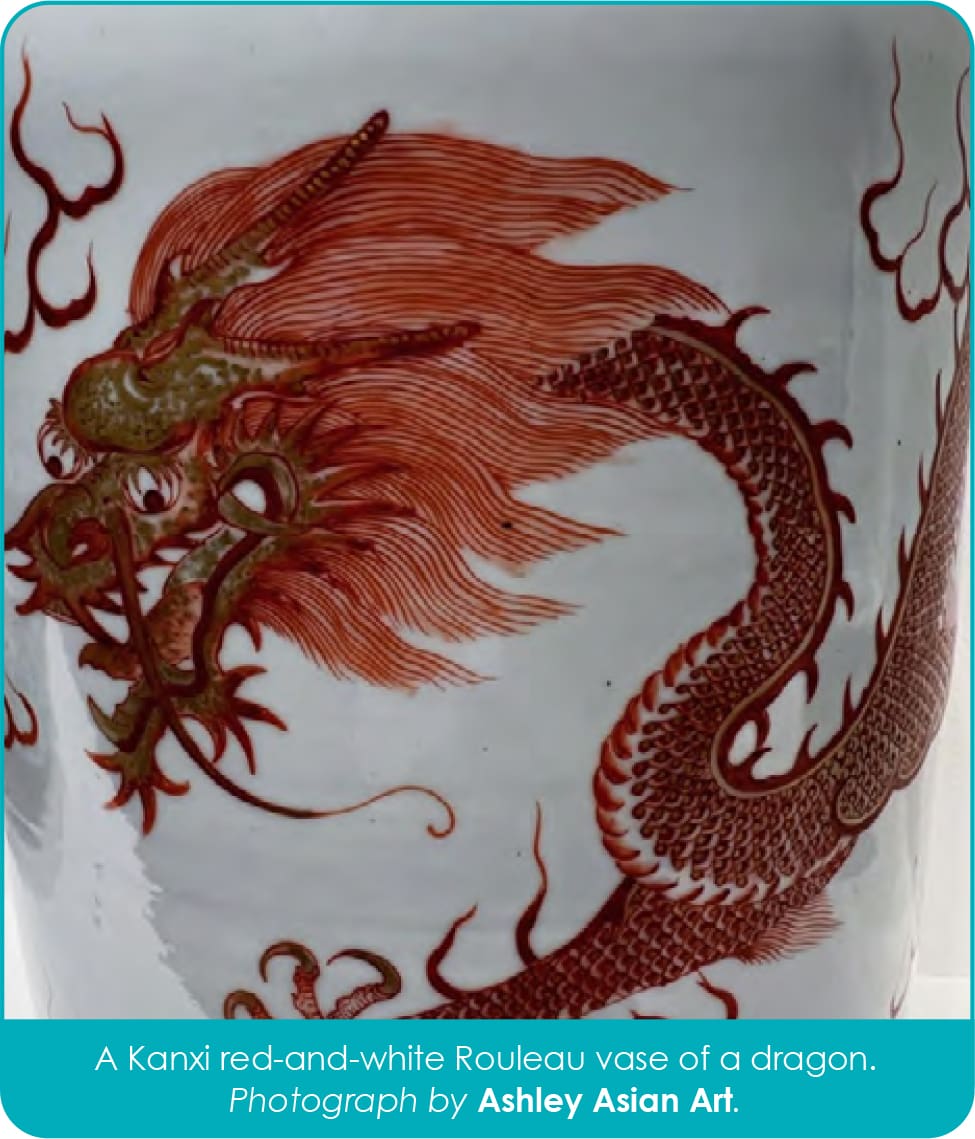

This year will be the year of the dragon, one of the most prevalent symbols in East and Central Asian material culture. People born in the year of the dragon are characterized as intelligent, lucky, and charismatic. Dragons have historically been depicted in forms such as embroidery, porcelain, sculpture, paintings, jade, ivory, and furniture.

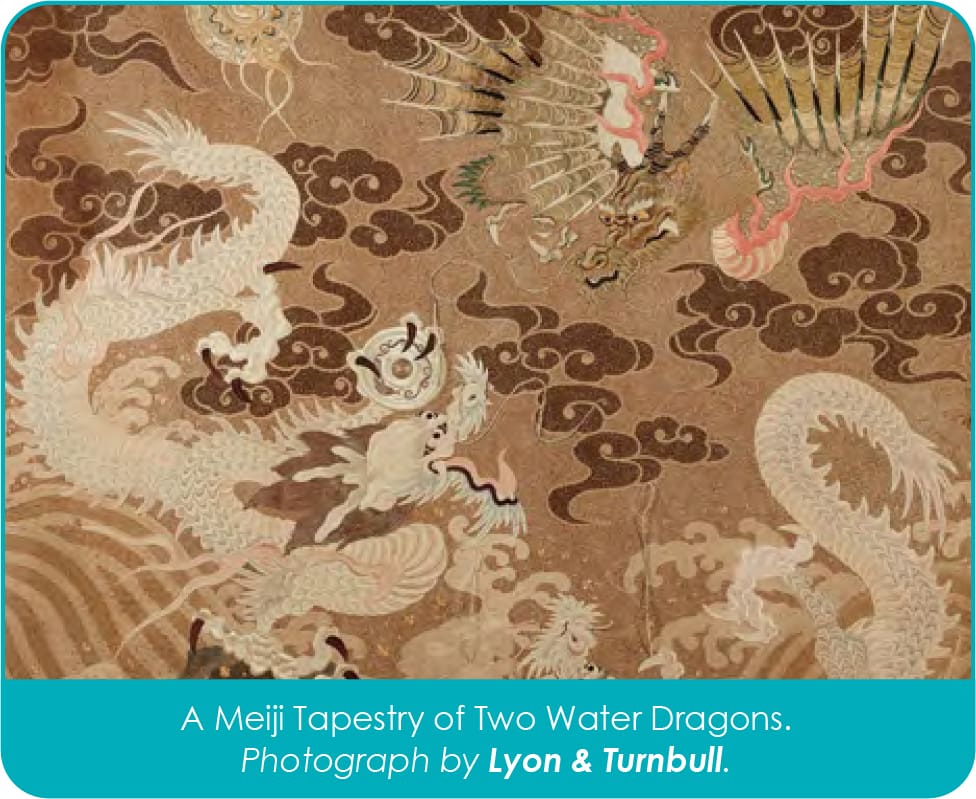

Dragons are particularly popular in embroidery, one of East Asia’s oldest decorative arts traditions, originating in China during the late Neolithic period. From the first century CE, silk embroidery technology spread to Japan, Korea, and Central Asia. Throughout the centuries, Chinese symbols, imagery, and embroidery techniques continued to have significant influences on embroidery practices across Asia. Dragons, also originating in China, have a long history in East Asian art forms. Dragon imagery dates to at least the Zhou period (1046-256 BCE), where it functioned as a totem to which small agricultural clans prayed for rain and protection from fires. This is why many East Asian dragons, such as those depicted in the much later Meiji tapestry below, are often depicted in ponds or seas. Water dragons symbolize prosperity for the owner. While imperial robes are the most famous form of dragon embroidery today, everyday water dragons comprise a far larger quantity of objects that have survived. This is particularly a result of the Ming Dynasty’s (1368-1644) rapidly growing merchant class, which increased the demand for silk embroidery and continued into the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was unprecedented Western demand for Chinese and Japanese silk embroidery, as China and especially Japan opened foreign trade. Export markets were already popular within Asia and Europeans had long enjoyed fine examples of handwoven dragon embroideries. As foreign demand grew, China and Japan mass produced silk embroidery in export markets for the first time. Improved technology and the advent of embroidery factories also contributed to this rapidly increasing market, which catered to Western tastes. In the early 20th century, silk was China’s largest export commodity. By the 1930s, this demand subsided due to the rise of synthetic fibers. Today, regardless of the medium, dragons continue to enjoy popularity in Asia and throughout the world.