Believed to be a gift from God, diamonds were first discovered in India in the 4th Century BC and were recognised for their hardness and strength. They were worn as adornments to ward off evil and provide protection in battle. Diamonds were also used as a medical aid; thought to cure illness and heal wounds when ingested. This was later dismissed, and it was thought that diamonds were highly poisonous; a rumour introduced to stop miners stealing diamonds by swallowing them.

Up until the 18th Century the only known source for diamonds was in India and their value was still considered much less than sapphires and rubies.

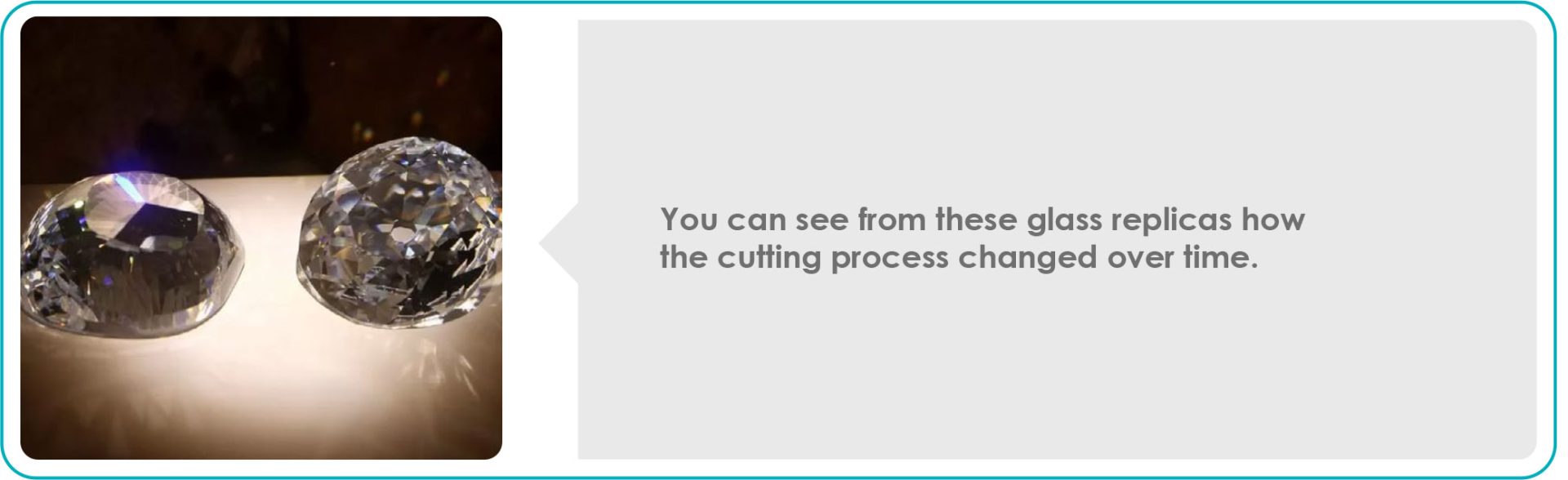

Alexander the Great opened a small trade between the East and the West in the mid-4th Century but it wasn’t until much later in the 14th and 15th century when diamonds entered Europe through Venice. They made their way north to Bruges, Antwerp and Amsterdam making these cities bustling diamond centres. It was at this point that European and Indian cutters begin to experiment with diamond cutting.

Point Cut Diamond

The earliest diamond cut is the point cut and was popular in the 15th Century. Cutters used diamond grit and olive oil to simply polish stones in their natural octahedral form. Olive oil was used due to its ability to tolerate the high temperatures caused by polishing.

Below is a diamond crystal in its natural octahedral form and a diamond ring set with multiple polished point cut diamonds.

Point cut diamonds are very rare as many of the original diamonds were re-fashioned as cutting techniques and styles changed. Here is an example of point cut diamond selling at auction for £11,000, well exceeding its pre-sale estimate of £1,800 – £2,400.

The Table Cut

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

This style of cutting possessed far better optical qualities than its predecessor, with greater brilliance and fire. It also displayed, when viewed from above, the impression of a table within a table, which fitted perfectly with Renaissance Europe’s love of classical proportions. The table cut became far more desirable than the point cut, which is why it is now rare to see examples of the point cut diamond as most were re-fashioned into the table cut.

Throughout the 16th and 17th century, variations of the table cut shape such as rectangles, triangles and tapered diamonds appeared.

Here are some more examples of diamonds with a table cut selling through auction.

The Rose Cut

The early 16th century saw the birth of the rose cut diamond. This made use of the flat rough instead of the octahedral crystal that we have seen so far. It proved the most efficient way to retain the weight of a flat crystal. The flat bottom and faceted domed top proved much more effective at displaying brilliance but not fire.

The Mazarin Cut

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

The Old Single Cut

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

In the early 17th Century, the mines in India were running low on diamond source and European cutters needed more stones to continue experimenting with cuts. Luckily at this time, while miners were panning for gold in Minas Gerais, Brazil, a few odd crystals, and pebbles were found. Not knowing what they had discovered the miners used these stones to keep score during games of cards. It wasn’t until an official saw them that they realised that in fact it was a new diamond source.

The discovery of alluvial deposits in Brazil meant great things for the cutters in Europe. The diamonds rivalled those of India, and Brazil became the main source of diamonds for Europe.

At this time, Europe had a great desire to experiment and evolve the diamond cut, and there was an increasing interest in optical science. With the aid of advanced lighting and the modernisation of technologies, the developments of the first modern brilliant cuts could start to take place.

The Peruzzi Cut

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.

Today, antique cushion cut diamonds remain extremely popular and sell very well. Here are some examples – notice how almost all exceed their pre-sale estimates.

The round brilliant cut diamond

Years of experimentation with cutting led to the production of the modern brilliant. We can see examples of the modern brilliant cut being traced to the 1800’s. Henry Morse had been trying to achieve the optically efficient cutting design. It was however Marcel Tolkowsky in 1919 who published his PhD thesis called Diamond Design. This used mathematical calculations that considered how to display both brilliance and fire in a diamond. Tolkowsky understood that if a diamond was cut too shallow or too deep that the light entering the stone would leak out of the side; this discovery was achieved by systematically analysing the optics of a diamond. Although this was revolutionary for its time, there have been other claims on the perfectly proportioned diamond. In 1940, Eppler produced the European Cut and later in 1970 The IDC (International Diamond Council) also produced a set of ideal ranges.

Compared Results

These differing proportions are all aiming to show the viewer the perfect amount of brilliance and fire. Brilliance is the reflection of light from the back facets when viewed from the top of the stone. Fire is the splitting of white light into the spectral colours as the light passes through inclined facets.

Altering the angle of the crown will affect the balance of brilliance and fire.

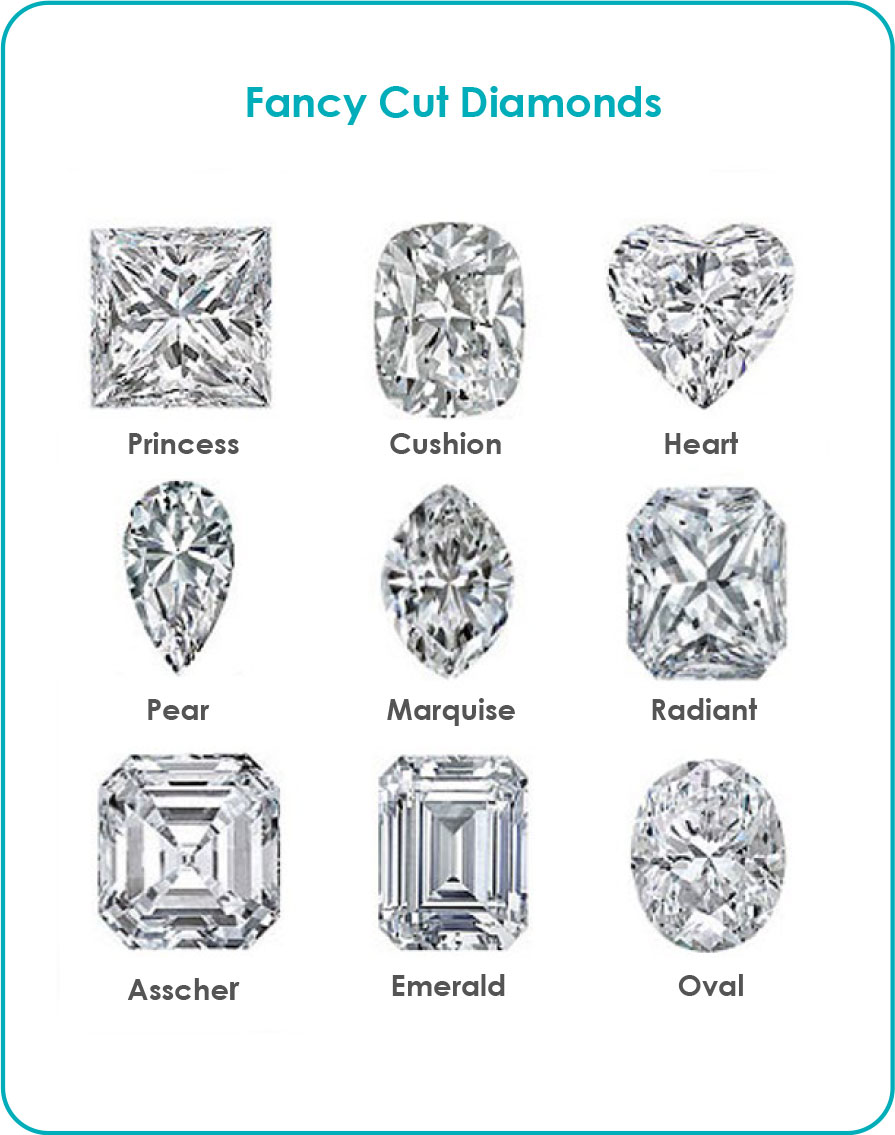

Fancy Cuts

In more recent times we have seen variations of the round modern brilliant cut diamond. Cutters have applied the same perfected proportions displaying great amounts of fire and brilliance and applied them to the Pear and Marquise cuts. The Pear and Marquise cuts have been around for centuries but never before displayed the optimum optical properties. Furthermore, this led to the production of more fancy shapes in the brilliant cut; heart cut and princess cuts are now examples of this. Triangular diamonds cut in this way were even named the Trillion cut.

With many attributing factors that have been considered in the cutting of diamond throughout its evolution; from a polished octahedral crystal through to the brilliant cut diamond displaying fire and brilliance, I wonder what the next seven centuries will bring. Will our future generations look back and consider the brilliant cut diamond a primitive design compared to what this stone, advanced technologies and creative cutters achieve in the future?

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.