Frank Auerbach, one of the most important and unique voices in contemporary art, passed away on 11th November, leaving a profound legacy in the world of painting. His death marks the end of an era, but his work—raw, visceral, and deeply human—will endure for generations to come. Auerbach’s paintings, which often appeared as works of fierce immediacy, were also the products of an unrelenting pursuit of truth and an intimate understanding of his subjects.

Frank Auerbach, one of the most important and unique voices in contemporary art, passed away on 11th November, leaving a profound legacy in the world of painting. His death marks the end of an era, but his work—raw, visceral, and deeply human—will endure for generations to come. Auerbach’s paintings, which often appeared as works of fierce immediacy, were also the products of an unrelenting pursuit of truth and an intimate understanding of his subjects.

Born in 1931 in Berlin, Auerbach’s life and art were shaped by history, by the upheavals of World War II, and by the quiet intensity of urban London. His parents were, jewish and were part of a thriving and integrated community fully assimilated into German society. His father, Max, who had served in the German army, was a lawyer, and his mother, Charlotte, had studied art. In 1939 his parents, concerned by the escalating, violent anti-semitism of Nazi Germany, dispatched Frank then aged 8 to England via the Kinder transport, he never saw them again. Sporadic letters from them conveyed via the Red Cross, ceased in 1943. Only much later did he learn that they had both been taken to Auschwitz early in March 1943 and both has died there that year. Talking about this time in his life on BBC radio’s ‘This Cultural life’ first broadcast on January 27th this year, he says “I am in total denial, and it has worked very well for me. To be quite honest I came to England, and it truly was a happy time. There’s just never been a point in my life when I wished I had parents.” Indeed, it did all work out well for him. He had the good fortune to find himself with some of the other Jewish Refugees at Bunce Court, a Quaker school in Kent which he loved and where he excelled in Art and Drama. In 1947 he was naturalised as a British Citizen and moved to London. He decided at the age of 16 to become an artist and attended art classes at Borough Polytechnic, now London South Bank University where the famous British painter David Bomberg taught him. Following this he was accepted at St. Martin’s School of Art.

It is tempting, to see Auerbach’s need for routine, his desire to keep the same sitters in the same place year after year, as a reaction to his childhood. Equally he lived within a very tight local orbit, and his subject matter comes almost entirely from his immediate environs of North London and his studio with its unfailingly regular and intensely loyal sitters.

In the early 90’s I had the pleasure of meeting one of these sitters, the art collector and academic Ruth Bromberg (1921-2010). Ruth sat regularly for Frank for two hours every Thursday for almost seventeen years. I asked myself why ? I found the answer in a letter Ruth wrote to Frank in 2008 published by the British Museum. Due to failing health Ruth reluctantly relinquished her duties as sitter, she wrote sadly to Frank as follows.’ I know how important your sitters are to you, and I would not wish to be the cause of disruption in your work schedule…I cherish my hours spent in the studio, my home away from home…Thursday afternoons will never be the same again and I feel the loss.’

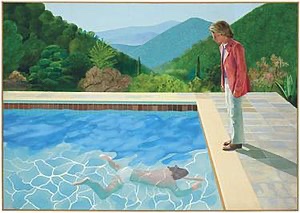

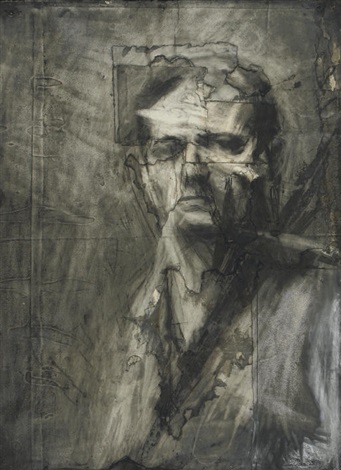

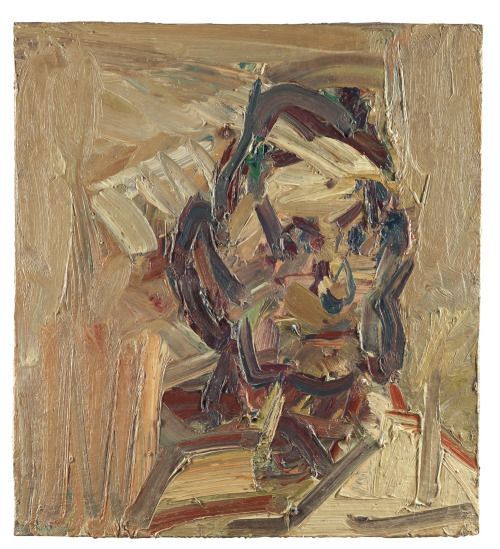

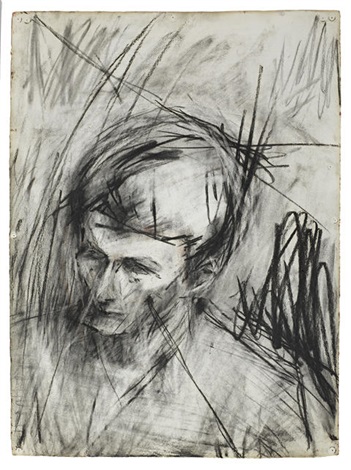

Frank’s brushwork, a relentless engagement with the surface of the canvas, was a testament to his tireless search for meaning beneath the layers of the everyday world. His portraits, are at once fiercely abstract and deeply personal, capturing the essence of the individual through the weight of paint and the tension of form.

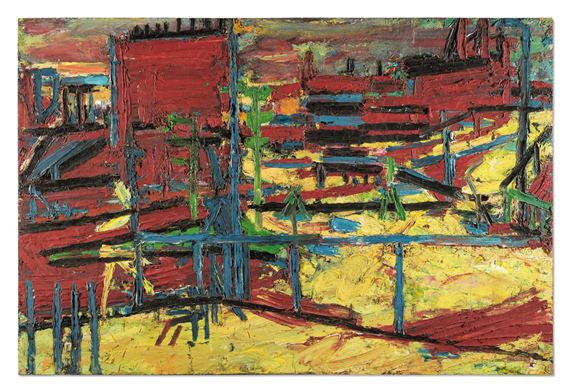

Auerbach’s paintings are known for their emotional depth and complexity, born of years of painstaking observation and reworking. He would often spend months, even years, refining a single portrait or cityscape, digging deeper each time into the texture and emotion beneath the visible surface. His relentless approach to painting was not only about achieving perfection but about honing a profound connection between artist and subject. Each stroke on the canvas, each layering of thick impasto, spoke to Auerbach’s belief in the struggle to capture truth and memory—never an easy task, but one that demanded everything of him.

His works were never concerned with trends or the fashion of the moment; instead, Auerbach’s paintings radiated an honesty and integrity that transcended time. His commitment to figuration, at a time when abstraction was dominant, and his resistance to simplification, made him a singular figure in British art. He was a master of his craft, but never complacent; always evolving, always questioning. He was a painter’s painter and his opinion really mattered to his fellow artists, particularly to his close friend Lucian Freud, who would not consider a work finished until Frank had seen and approved it.

Throughout his life, Auerbach remained a fiercely private individual, rarely seeking the limelight. Yet, his work spoke loudly, its emotional power reverberating in galleries and collections around the world. His portraits were not just depictions of faces—they were psychological explorations, capturing the depth of the inner life of his subjects. His cityscapes, on the other hand, were a meditation on the persistence of memory, as well as the transformation of place over time.

Auerbach’s influence, though perhaps understated in some circles, was profound. His legacy is not merely in the works themselves but in the way he taught us to see: to engage with the world with intensity, with a fierce awareness of its complexities and contradictions, and to never settle for the surface.

In his passing, the world has lost a giant. But the impact of Frank Auerbach’s work will continue to inspire and challenge us for many years to come. His paintings will live on, continuing to confront us with the same questions he asked of himself throughout his career: ‘What does it mean to capture a moment, a face, a city? How can we, as artists and as people, approach the world with the depth and urgency it deserves?’

Rest in peace, Frank Auerbach. Your vision, your dedication to your art will never be forgotten.

Jonathan Horwich, 14/11/2024

To find out about our art valuation service call us on 01883 722736 or email [email protected]