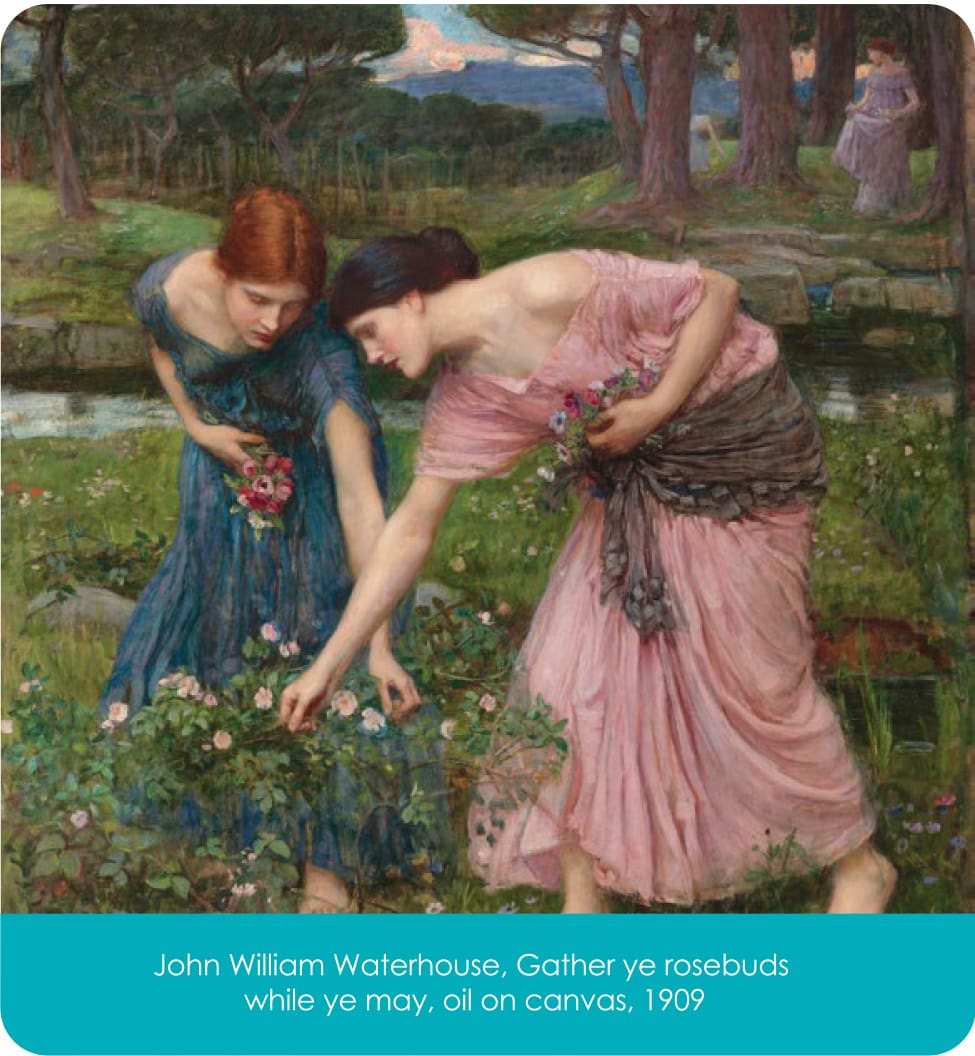

The poem ‘To Daffadills’ beginning ‘Faire Daffadills, we weep to see/You haste away so soon’ graces many an anthology. It is often mistakenly thought of as by Wordsworth. But the author was Robert Herrick, a 17th-century country vicar who made a speciality of lyric verse in short lines. Although Herrick’s life was a quiet one, yielding few facts, his work displays an appealing hedonism and deep preoccupation with the fleeting nature of time. He penned the famous lines: ‘Gather ye Rose-buds while ye may/Old Time is still a flying’ which open the poem ‘To the Virgins, to make much of Time’.

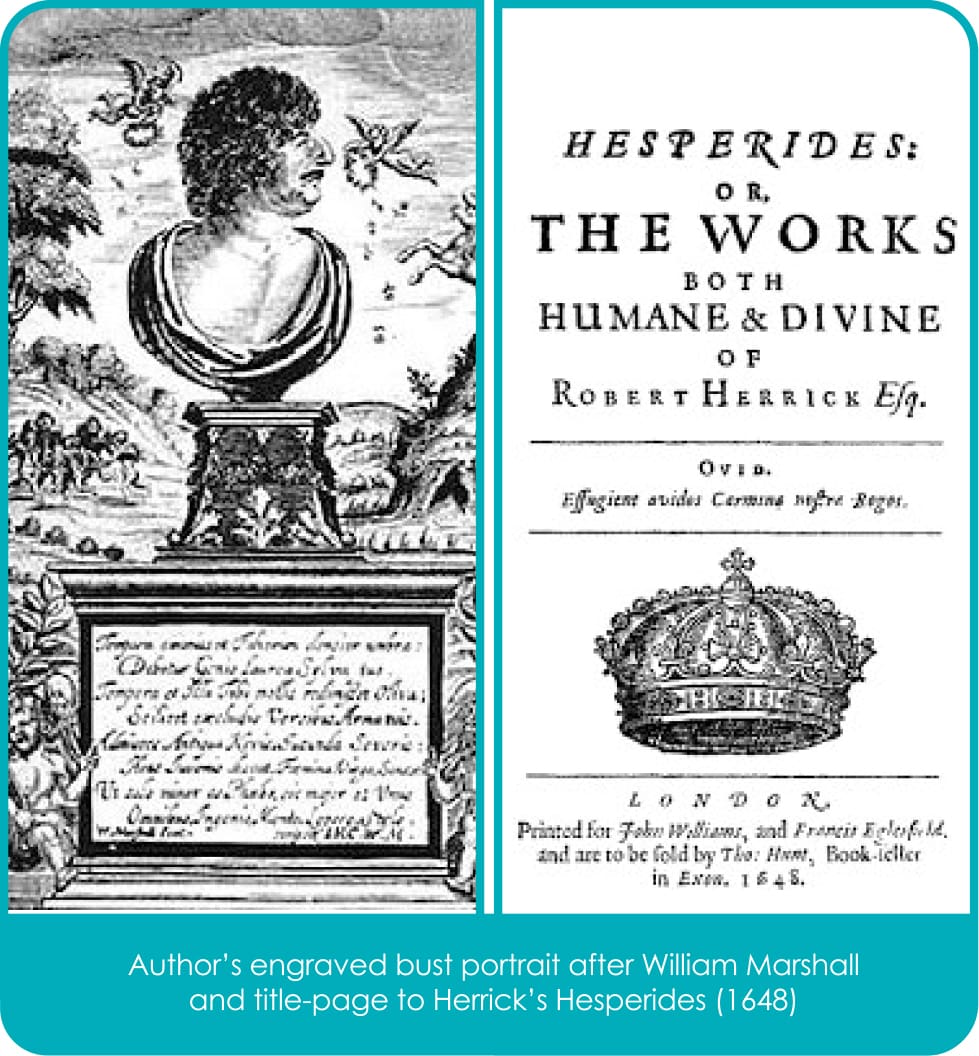

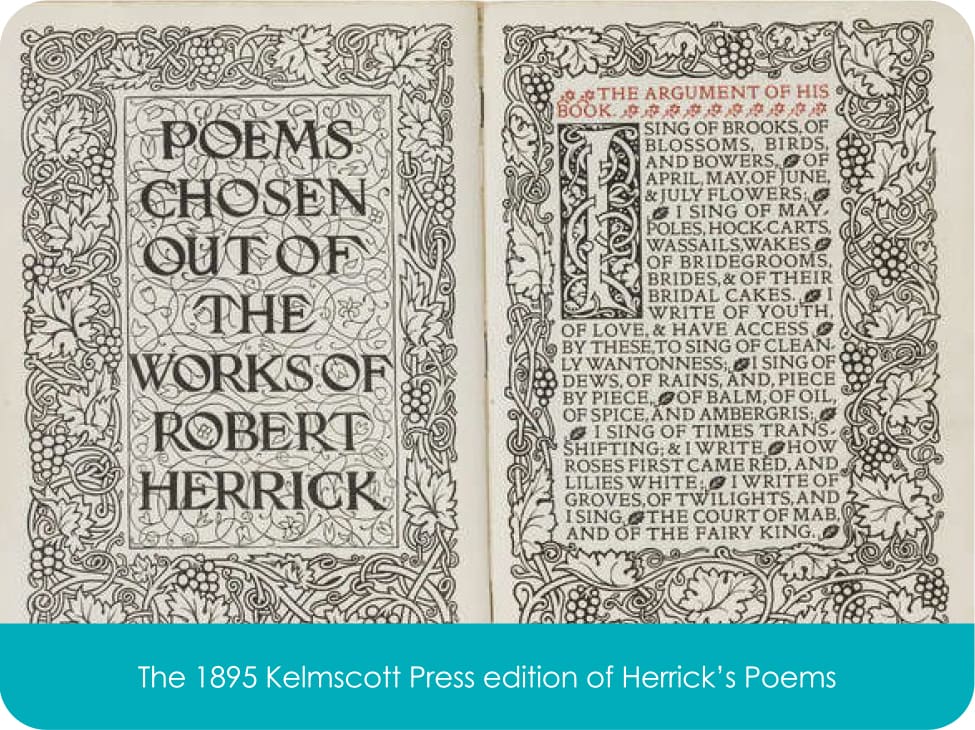

Hesperides: or The Works both Humane and Divine of Thomas Herrick, printed in London for John Williams and Francis Eglesfield, in 1648, contained the poet’s collected verse. As the ‘humane’ poems occupy 398 pages of the octavo volume, compared to just 79 pages for the divine, one can deduce that sacred subjects were not his favourite. Hesperides remained an under appreciated book for two centuries, though Anthony Wood recorded that the volume made Herrick ‘much admired in the time … especially by the generous and boon loyalists’ (Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, 1721, II, pp. 122-123). It is a rare book today. Sotheby’s sold the Stockhausen copy for $35,000 in 2015, and the Huth copy for £15,000 in the same year.

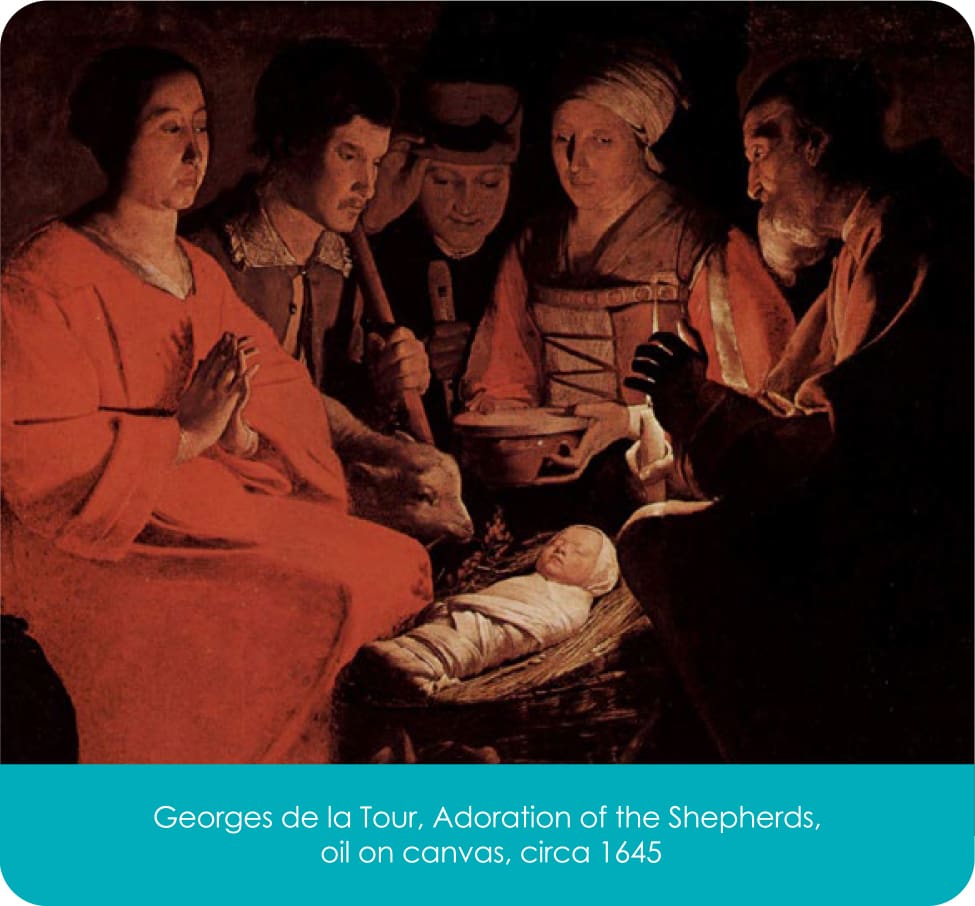

One subject that seems to bridge the secular and religious divide in Hesperides is Christmas. Herrick’s Christmas poems include two splendid carols, sung before James I at Whitehall and set to music by Henry Lawes, as well as ‘An Ode of the Birth of Our Saviour’. In the latter, the poet is deeply shocked that the ‘pretty Baby’ and ‘Kingly Stranger’ should have his birthplace in a ‘base Out-stable’, preferring him to possess a cradle of ‘interwoven osiers fragrant posies/Of daffodils and roses’. This is the country cradle of rushes deployed in nativity scenes such as Georges de la Tour’s Adoration of the Shepherds. ‘As Gospel tells’ the actual cradle ‘Was nothing else,/But here a homely manger’. But the poet promises to totally transform the conditions spoken of in the Gospel. The baby’s rough clothing will be exchanged for silks sewn with ‘precious jewels’ and ‘lily-work’, the manger will be turned into a chamber of ivory and amber:

But we with silks, not crewels,

With sundry precious jewels,

And lily-work will dress thee;

And as we disposses[s] thee

Of clouts, we’ll make a chamber,

Sweet babe, for Thee, of ivory,

And plaister’d round with amber.

The allusions to silks, jewels and other precious commodities would have been made from a standpoint of knowledge as Herrick was born into a family of goldsmiths in 1591, the seventh child of Julia Stone and Nicholas Herrick. He was named after an uncle, Robert Herrick (or Heyrick), Member of Parliament for Leicester. Tragedy struck when, the year after his birth, his father died in a possible case of suicide (he fell from an upper window of his house in Cheapside two days after making his will). Fortunately, his uncle provided for him.

In 1607 Herrick was apprenticed to another uncle, Sir William Herrick, a goldsmith with close ties to James I. He got through six years of the ten year apprenticeship, then sought a different future in law. At the comparatively advanced age of 22, he matriculated at St. John’s College, Cambridge. Surviving letters to Sir William indicate that his nephew’s finances could barely cope with a year’s carousing at St. John’s, and he moved to Trinity Hall where he spent three more years reading law, graduating in 1617.

For reasons we don’t know Herrick never became a practising lawyer. In the twelve years between his graduation from Cambridge in 1617, and his appointment as vicar of Dean Prior ‘tantalisingly little’ is known for certain about his life (see poetryfoundation.org). It is widely accepted that he spent much of his time in London. Writing in the mid- 19th century, Henry Vizetelly described him as being ‘in familiar intercourse with the chief wits, and writers of the age. Herrick had for his early intimates Ben Jonson, [John] Selden, William Lawes the eminent composer, and Endymion Porter, groom of the chamber to the King, besides many others of equal note’ (Christmas with the Poets, London, David Bogue, 1851).

The teacher/pupil relationship with Ben Jonson (1572-1637) was real enough for Herrick to address five poems to him, including an epitaph. The first verse of ‘His Prayer to Ben. Jonson’ pays due homage to the great classicist, as a playwright ranked second only to Shakespeare:

When I a Verse shall make,

Know I have praid thee,

For old Religions sake,

Saint Ben to aide me.

Endymion Porter (1587-1649) was a diplomat and patron of the arts, fiercely loyal to Charles I, who also wrote verses. Both he and his wife, Olivia, niece to the Duke of Buckingham, were painted by van Dyck. While Herrick himself never married, he was preoccupied with women as a subject, writing about Julia and other ‘mistresses’ in as many as 158 poems. It is possible that none of the women he so admired in verse existed as real people.

It may have been owing to the influence of Endymion Porter that Herrick briefly obtained the position of assistant chaplain to the Duke of Buckingham, playing his part in the catastrophic expedition to free the French Huguenots on the Ile de Ré in 1627. But that was the beginning and end of his military career. He was appointed to the living of Dean Prior in South Devon in 1629, a post he took up in 1630, perhaps with the conscious aim of having more time and opportunity for his poetry.

Dean Prior in the 17th century must be regarded as extremely remote and therefore ideal for a hermit like Herrick. The nearest towns, Exeter and Plymouth, were almost a day’s ride away. London was a five-day trek. Though the vicarage next to the church was by no means ostentatious, the poet-clergyman never agitated for change and lived in Dean Prior for a total of 31 years, the period split into two by the civil war.

Whereas Robert Herrick was a royalist and traditional Anglican, and is often grouped among 17th-century ‘cavalier poets’, the population of the west country was strongly sympathetic to the Puritan cause. The Civil War which began in 1642 made his position precarious; in 1647 he was among 142 Devonshire clergymen expelled from their parishes because of their loyalty to the King. He went to live in Westminster, where he could be supported by his family and friends. His first period as vicar had lasted for 17 years. On his return to Devon at the Restoration of 1660, he served for 14 years more, ending with his death in 1674. While the 14th-century parish church of St. George the Martyr still stands, his gravestone has disappeared, exactly as he predicted it would.

Herrick would certainly have missed old friends on his return to the capital. Ben Jonson had died ten years earlier, William Lawes had been killed at the siege of Chester, Endymion Porter had fled abroad, returning to England only to die in poverty in 1649. ‘Selden alone survived in the enjoyment of a green old age’ (Vizetelly). New literary friendships were forged with Charles Cotton, translator of Montaigne and contributor to The Compleat Angler, and Sir John Denham, the bard of Cooper’s Hill. Herrick also had his octavo volume of poetry, largely written in Devon, to think about for the press. Being close to the printers must have been a stimulus despite the existence of this biblical quatrain preceding the errata:

For these transgressions which thou

here dost see

Condemne the Printer, Reader,

and not me;

Who gave him forth good Grain,

though he mistook

The Seed; so sowed these

Tares throughout my Book.

Herrick revised his work, carefully considered what order to place the poems in, and even went to the trouble of versifying the table of contents. The religious poems have an independent title, His Noble Numbers, and separate pagination; dated 1647, the year of his return from Dean Prior, they may originally have been intended for separate publication

Hesperides contains some 1400 lyrics in all, of which there are sixteen or so Christmas poems. While this is only a fraction of the content, it is hard to think of any other poet who has taken such pains to record the festivities. We are used to thinking of indulgent Christmases as a Victorian invention. Reading Herrick’s accounts of wassailing and other Christmas ‘ceremonials’ will show this to be a misconception. For Christmas traditions in 17th-century Devon are time honoured and have no identifiable beginning.

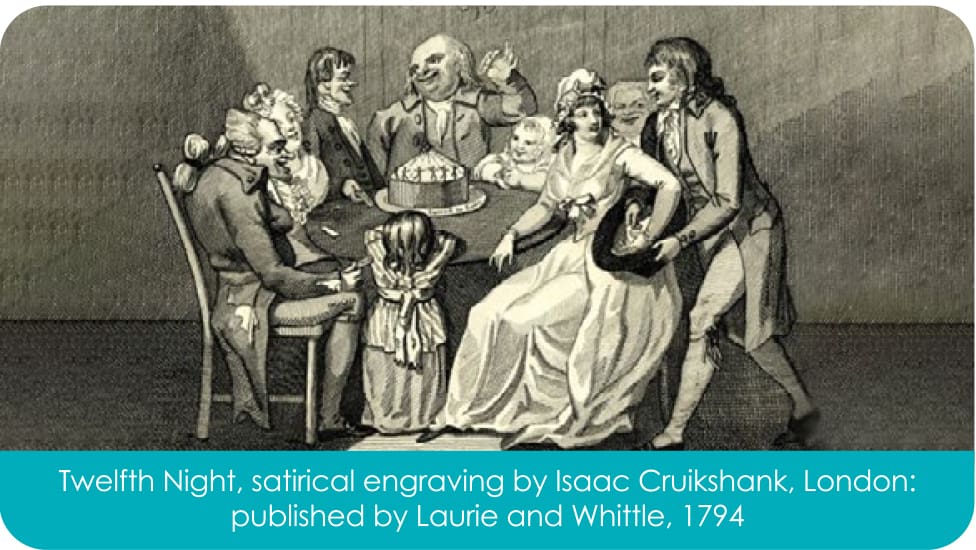

As opposed to being treated as a single day in modern fashion, Christmas drinking and feasting lasts for a whole season, coming to another climax on Twelfth Night, and even extending up to Candlemas Eve on 1st February. There is little if any mention of young children. It is maidens and young men who are at the centre of Herrick’s Christmas, and happy carousing, happy eating of plum pies and pastries, are the order of the day.

‘Ceremonies for Christmas’ is primarily about the lighting of the Christmas log. The speaker demands that it be brought into the room, accompanied by a suitable uproar of noise from the ‘merry boys’. Thanks to ‘my good dame’, a generous hostess, drinking opportunities are unlimited:

Come, bring with a noise, My merry, merry boys, The Christmas log to the firing; While my good dame, she Bids ye all be free And drink to your heart’s desiring.

The speaker next demands that the new block of wood for the Christmas fire be lit with a piece of the old wood, saved from the previous Christmas: ‘With the last year’s brand/Light the new block’. The middle stanza also refers to the ‘psaltries’ (or guitars) that have to be played as the wood kindles, bringing ‘sweet luck’. Once these ceremonies have been performed, the orders are to:

Drink now the strong beer,

Cut the white loaf here;

The while the meat is a-shredding

For the rare mince-pie,

And the plums stand by

To fill the paste that’s a-kneading.

It’s an abrupt end but typically matter of fact in manner. From this poem alone Herrick’s approval of wassailing or drinking to excess is unquestionable. However, his poem ‘Wassail’, written in 3-line stanzas, is ironically so called, for it takes to task the miserly household that refuses to open its doors for Christmas. Nothing is so grievous as the lack of beer. ‘Alas! We bless, but see none here/That brings us either ale or beer;/ In a dry house all things are near’. Neither are there any happy noises in a house ‘Where chimneys do for ever weep/For want of warmth, and stomachs keep,/With noise, the servants’ eyes from sleep’.

‘Twelfth Night or King and Queen’ describes the ‘cake full of plums’ (the ancestor of our Christmas pudding), and the election of the Twelfth Night king and queen by the successful recovery of a bean and pea hidden inside it: ‘Now, now the mirth comes/With the cake full of plums,/Where bean’s the king of the sport here’. Once the election is decided, the invitation is issued to all to ‘…make/Joy-sops with the cake’, and drink to a cup’s limits:

… let not a man then be seen here,

Who unurged will not drink,

To the base from the brink,

A health to the king and queen here.

The reference to ‘lamb’s wool’ in the penultimate stanza becomes less puzzling once ‘… a bowl full/With gentle lamb’s wool’ is recognised as the Devonshire name for a bowl of spiced beer. Herrick even provides a list of ingredients: ‘sugar, nutmeg and ginger,/With store of ale, too’, all necessary ‘to make the wassail a swinger’. Guests are encouraged to wassail the king and queen, and an assurance is given that the drinking is all good natured:

… though with ale ye be wet here,

Yet part ye from hence

As free from offence

As when ye innocent met here.

Herrick’s poems could be very short indeed. Two of the Christmas lyrics consist of only one 4-line stanza. ‘Another to the Maids’ warns the maids in a household against kindling the Christmas fire with ‘unwash’d hands’, the belief being that this will only put the fire out:

Wash your hands, or else the fire

Will not teend to your desire;

Unwash’d hands, ye maidens, know,

Dead the fire, though ye blow.

A second short poem, called simply ‘Another’, forms a companion-piece to the first, advising the maids to wassail the fruit trees in order to improve their fertility:

Wassail the trees, that they may bear

You many a plum and many a pear:

For more or less fruits they will bring,

As you do give them wassailing.

At fifty lines in length ‘A New Year’s Gift sent to Sir Simon Steward’ was one of the more ambitious Christmas poems. It is a composition that can be dated. Sir Simon (1575-1632) had been a student at Trinity Hall living on there for some years after his graduation. Besides combining the roles of a Justice of the Peace, High Sheriff, and MP, he was an occasional poet. Herrick sent him his long string of rhyming couplets in January, 1624, starting that no kind of bad political news would be the subject his letter. Instead Sir Simon should expect to find:

… here a jolly

Verse, crown’d with ivy and with holly,

That tells the winter’s tales and mirth,

That milkmaids make about the hearth,

In the mid stage of the poem various ‘Christmas sports’ and customs are affectionately named or mentioned, not least the choosing of the Twelfth Night king and queen. Sir Simon and his household are urged to read the poem, and ‘Remember us in cups full crown’d’. But the mood is not all joyful; in the final part Herrick touches on his favourite theme of the brevity of time, and insists that thoughts of future Christmases are preferable to ‘fled Decembers’. Better, it is suggested, to drink on until Father Bacchus ‘twirls the house about your ears’, attaching ‘your cares’ to the past year not the future one:

Then as yet sit about your embers,

Call not to mind those fled Decembers,

But think on those that are t’appear

As daughters to the instant year:

Sit crown’d with rosebuds, and carouse

Till Liber Pater twirls the house

About your ears; and lay upon

The year your cares that’s fled and gone.

However, the last piece of advice is light hearted. It is to enjoy the Christmas plays, and ‘Frolic the full twelve holidays’.

‘Ceremonies for Candlemas Eve’ is another poem about transience and the need to avoid regret. Who hasn’t taken down the Christmas decorations with a sense of relief and a feeling that it’s time to move on? Herrick captures that feeling, beginning his poem with the call to take down the Christmas greenery on Candlemas Eve (i.e. 1st February). He is happy to see a new plant, ‘the greener box … domineer’ instead. However, the box also has its time limit in the house, holding sway only up to ‘dancing Easter day’. His poem begins:

Down with the rosemary and bays,

Down with the mistletoe;

Instead of holly, now up-raise

The greener box (for show).

The holly hitherto did sway:

Let box now domineer

Until the dancing Easter day,

Or Easter’s eve appear.

As the year progresses, there is a recognisable succession of plants traditionally used for adornment. The ‘youthful box’ renews houses but when ‘Grown old, surrender must his place/Unto the crisped yew’. The yew is followed by the birch ‘And many flowers beside’ which do honour to Whitsuntide. In the final stanza, ‘green rushes’, ‘bents’ (so called because they are flowers which bend or droop?) and ‘cooler oaken boughs’ are considered ‘comely ornaments/To re-adorn the house’. But the poem does not end there.

Herrick adds an extra couplet to remind us that, as greenery goes in and out of favour in the house, so the shifts of time effect change in all things:

Green rushes, then, and sweetest bents,

With cooler oaken boughs

Come in with comely ornaments

To re-adorn the house.

Thus times do shift; each thing

his turn does hold;

New things succeed,

as former things grow old.

Through these varied poems Robert Herrick gives us a remarkably strong picture of what a 17th-century Christmas in Devon was like, something to think about as we are enjoying our Christmas in the early 21st century.

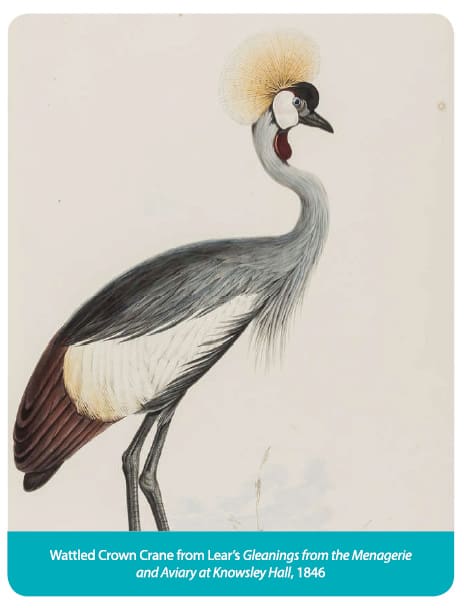

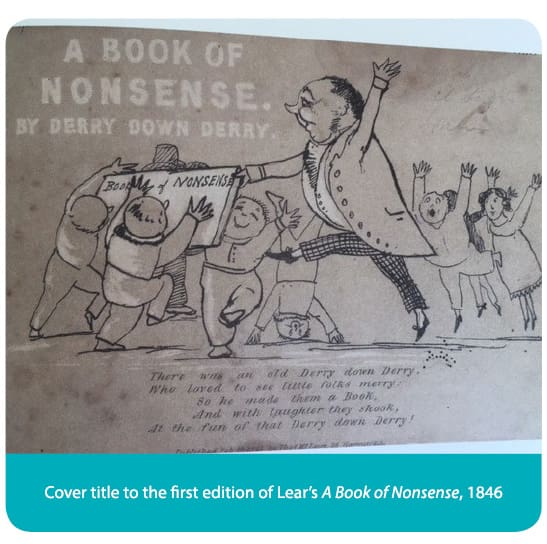

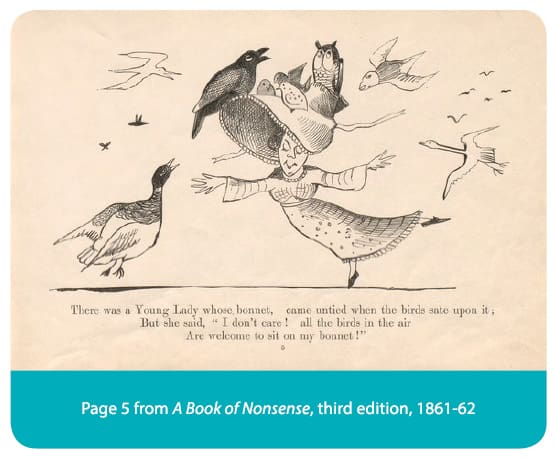

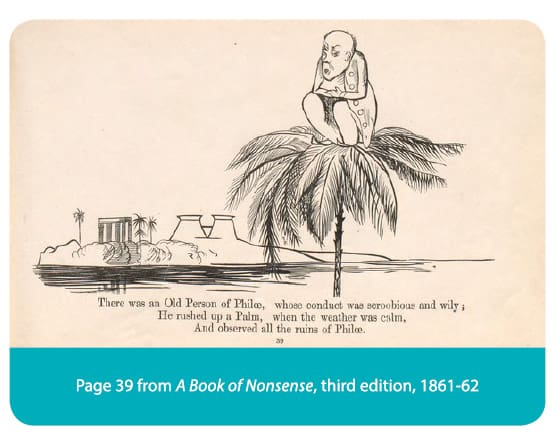

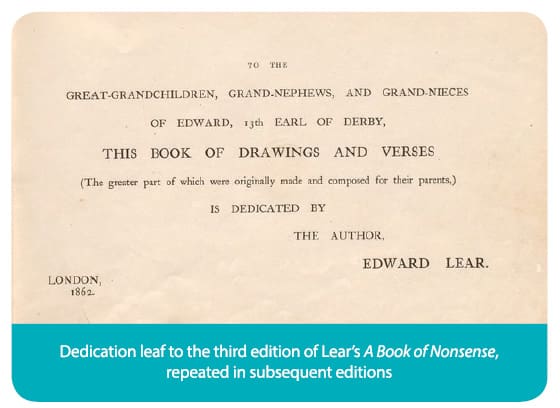

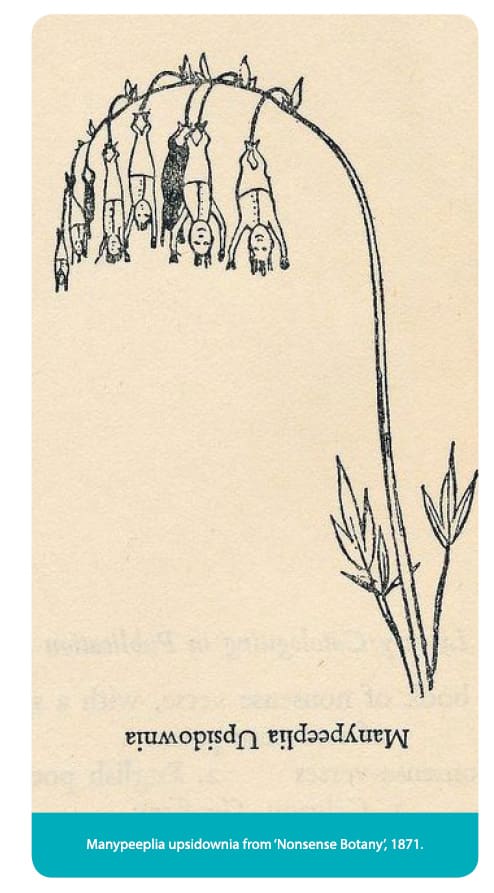

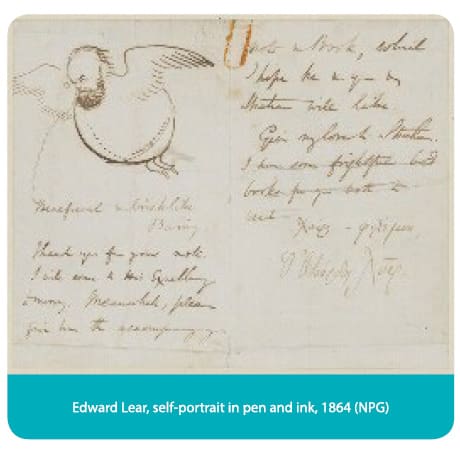

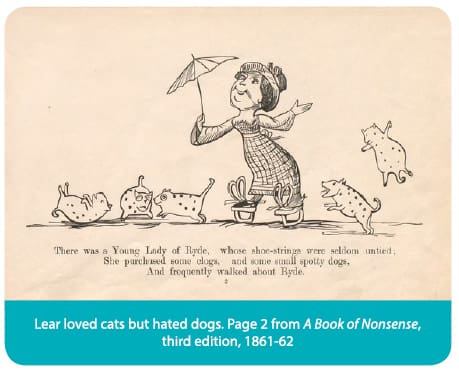

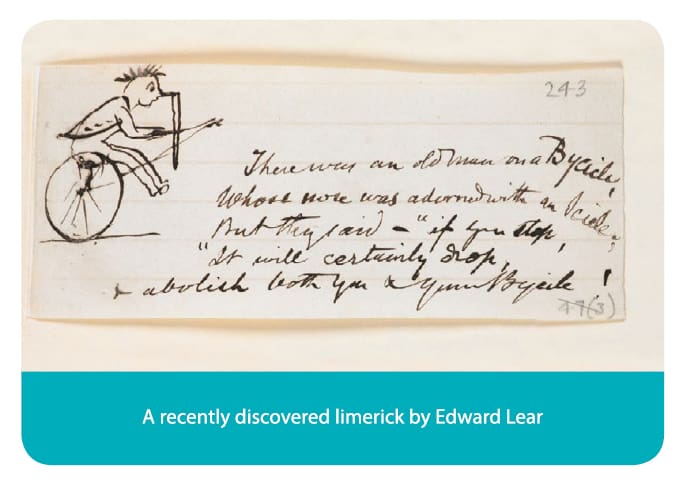

Born in the village of Holloway on 12 May, 1812, he was the twentieth child in a family of twenty-one children. His devoted older sister, Ann, brought him up in a separate home from his countless siblings. Suffering from epilepsy, chronic asthma and weak eyesight, his education was mostly at her hands. His father, a stockbroker of Danish background, had understandable money troubles. Fortunately, Lear’s natural ability as an artist and draughtsman enabled him to earn a living from the age of sixteen, and ultimately win the wholesale admiration of society. Between July and August 1846 he visited Queen Victoria at Osborne House in order to teach her ‘landscape painting in watercolours’. But he was also faced with the difficulties of being a homosexual in the morally censorious climate of mid-19th-century England. While he was to find living abroad easier, he was always a lonely man and this comes across in the sad, forlorn quality of his nonsense poems.

Born in the village of Holloway on 12 May, 1812, he was the twentieth child in a family of twenty-one children. His devoted older sister, Ann, brought him up in a separate home from his countless siblings. Suffering from epilepsy, chronic asthma and weak eyesight, his education was mostly at her hands. His father, a stockbroker of Danish background, had understandable money troubles. Fortunately, Lear’s natural ability as an artist and draughtsman enabled him to earn a living from the age of sixteen, and ultimately win the wholesale admiration of society. Between July and August 1846 he visited Queen Victoria at Osborne House in order to teach her ‘landscape painting in watercolours’. But he was also faced with the difficulties of being a homosexual in the morally censorious climate of mid-19th-century England. While he was to find living abroad easier, he was always a lonely man and this comes across in the sad, forlorn quality of his nonsense poems.