The original Parliament of Scotland (Estates of Scotland) existed from the early 13th century right up until 1707. Following The Acts of Union 1707, the Kingdom of Great Britain was formed, the Parliament of Scotland closed, and a Parliament of Great Britain was created.

Fast forward through many turbulent years and the first elections for the Scottish Parliament were held on 6 May 1999.

On 1 July 1999, the Scottish Parliament was officially opened by Her Majesty The Queen and was awarded its full law-making powers, and a competition was launched to design a new building. This was ultimately won by Spanish architect the late Enric Miralles, with his firm EMBT, in collaboration with RMJM and Ove Arup & Partners.

The completion of the Scottish parliament in the Autumn of 2004 brought excitement, anticipation and pride to Edinburgh and the rest of Scotland, representing power and debate north of the border.

The building is an arresting example of contemporary architecture, situated in Holyrood Park at the foot of Arthurs Seat and opposite Holyrood Palace. Taking inspiration from not only the immediately surrounding landscape but further afield, the ponds to the front concourse representing the lochs of Scotland.

The interior is an eye-catching mix of granite, oak and glass, bringing in shafts of light to this remarkable space. Not only the perfect location for debating the important issues of Scotland but a perfect backdrop to showcase a wide range of artistic talent.

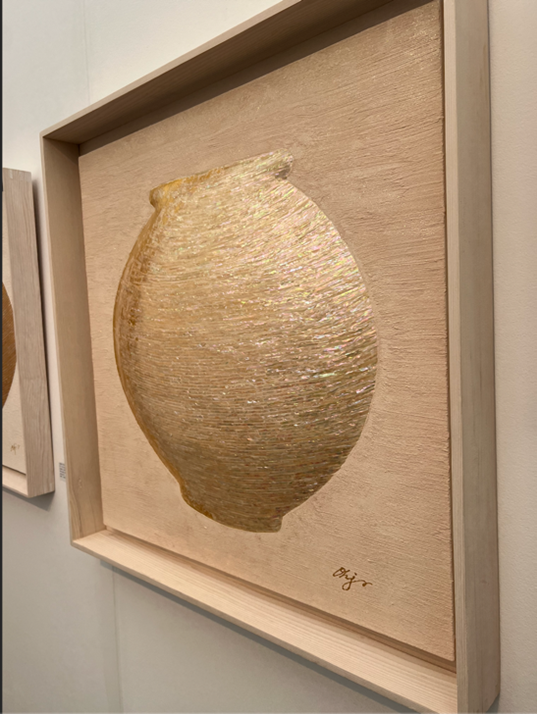

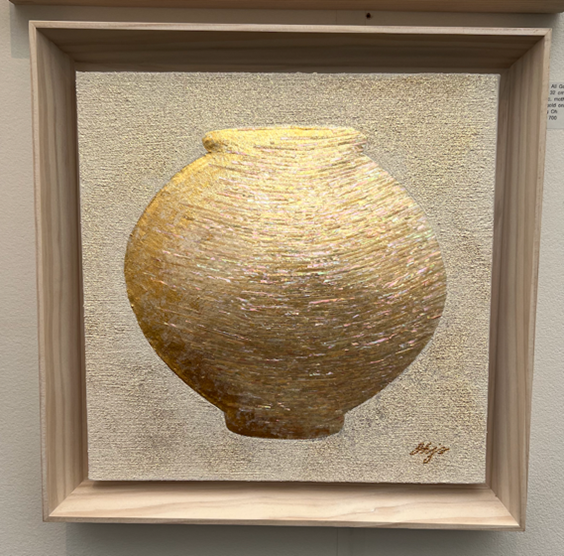

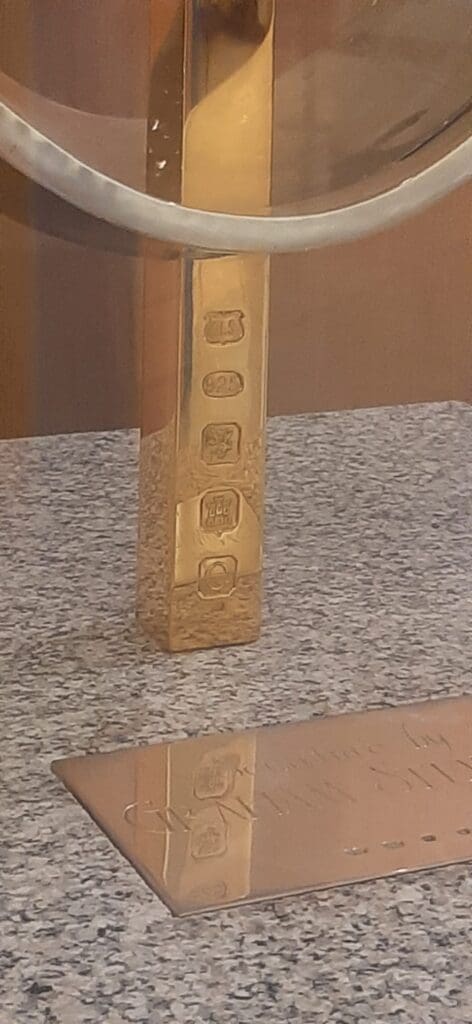

Entering the large reception my eye was drawn to the Honours Regalia sculpture. Standing just over 50cm high this modern representation of the crown, sword and sceptre was commissioned by the Incorporation of Goldsmiths of The City of Edinburgh. Made by renowned silversmith the late Graham Stewart, it is part plated in 24ct gold and bears the distinct Edinburgh castle hallmark. Presented by Her Majesty The Queen at the opening of Holyrood in 2004 this deeply symbolic sculpture takes pride of place.

Moving round to the left is the striking installation ‘Psalmsong 2003’ by Alison Kinnaird. Mounted on the curved wall and beautifully lit, this atmospheric and haunting work represents the circle of life and requires more than one viewing!

‘The Anchorites’ by Will Maclean is a symbolic and imaginative sculpture of a small boat on an unknown journey, viewed from above, alluding to early Celtic monks seeking isolated spots for meditation.

The central figurative shield shape contains male and female attributes alongside the basics for survival – corn, grinding stones and wood. Born in Inverness and inspired by Highland culture, the sea and emigration, Will Maclean studied at Gray’s School of Art after several years at sea.

Approaching the wide staircase the bright marine colours of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s deconstructed boat is striking against the plain concrete wall. Working in collaboration with Peter Grant, this is a humorous take on the over lapping boards which form the coble.

The original coble boat has its roots in Whitby, hence the registration number WY, but these flat-bottomed boats were also used to fish for salmon in Scotland.

Following the sweeping staircase, we come across ‘Quartet 1980’ by James Munro. Shining in the Scottish summer sun, this abstract steel sculpture represents the shadows cast by a quartet of musicians. Music played a large part in Munro’s life; he became an accomplished vibraphone and keyboard player following the post WWII jazz movement. The family had a large impact in arts and music in East Lothian. Today you can follow The Munro family Public Art Trail across East Lothian and Edinburgh.

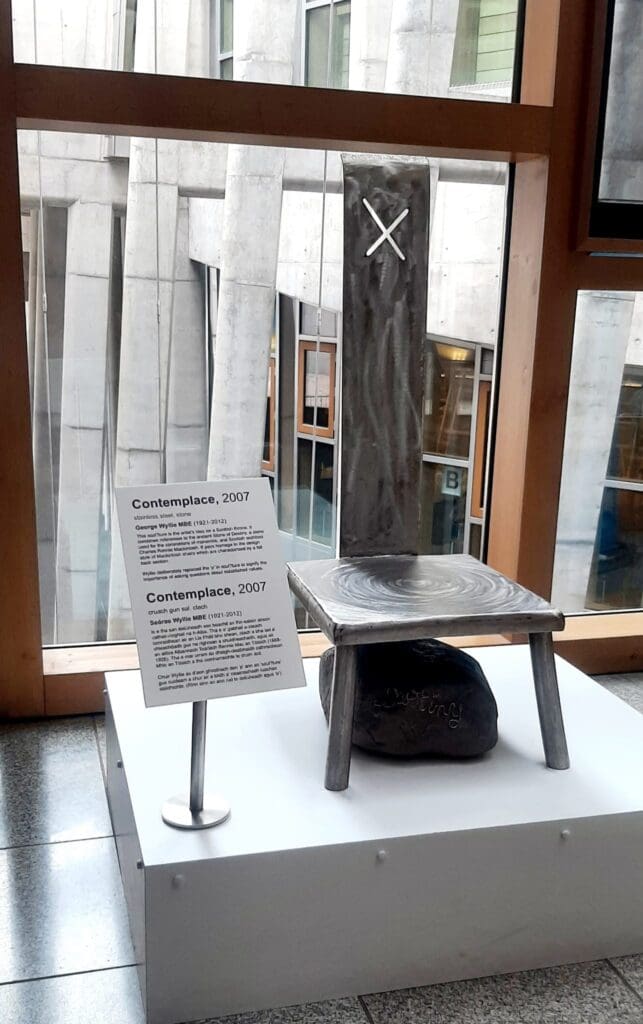

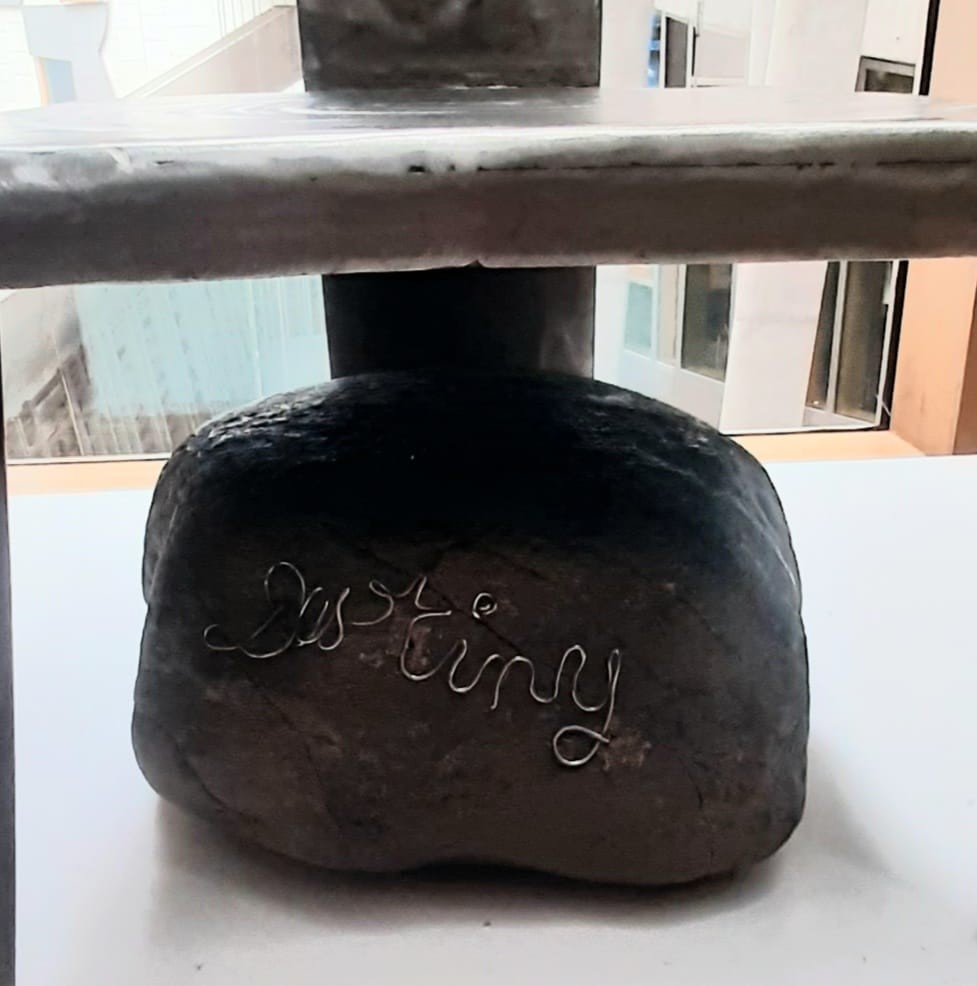

With reference to the distinctive forms of the furniture of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the steel chair with its tall back sits above his playful interpretation of The Stone of Destiny.

Wyllie left his job as a Customs and Excise officer in Greenock in 1980 to study art and proclaimed himself to be a “scul?tor” as a result of him being unsure if he was an actual sculptor.

It’s evident that much knowledge and consideration went into the selection of the works to be displayed within The Scottish Parliament. It’s a dynamic and varied collection which truly represents the heritage of Scotland and the pride and traditions of its people.

For tours and general information see parliament.scot

To arrange a valuation of your items, call us on 01883 722736 or email us at [email protected]