Colin T. Fraser, Consultant Specialist

So much of what we see and value day to day sadly can’t tell us much of its personal story from creation, survival and provenance. When we do come across an item which can it is plain to see, (usually with some digging and research) the rewards and interest that can result are marvellous.

We often say that provenance changes an item completely; it lifts it from being a standard piece to a ‘treasure’. In this case the understanding of an object not only elevates the story to one of exceptional Royal provenance, (by no fewer than eight reigning monarchs) but one of international legal cases and Royal rifts – the likes of which would not have been seen

until…Megxit!

These standard spoons are just that – fine examples of standard mid-18th century tablespoons which could have graced any middle or upper class British home.

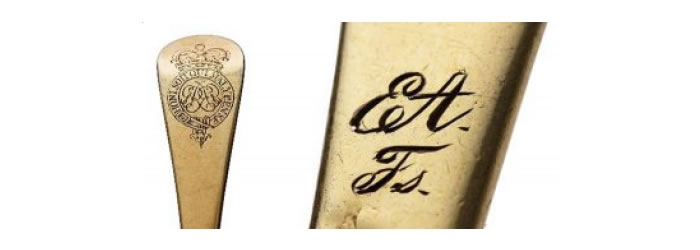

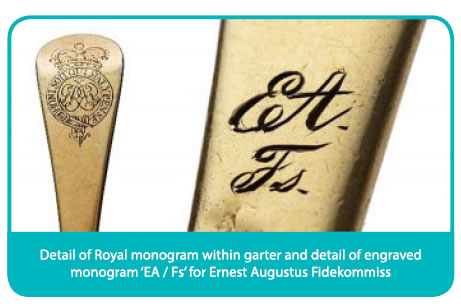

However, their Royal lineage becomes clear when looking at the reverse of the handle which is engraved with an intertwined mirrored monogram GR, within a strap and buckle bearing the Motto HONI SOIT QUI MAL Y PENSE,

(meaning ‘shame on anyone who thinks evil of it’ , being the motto of the Most Excellent Order of the Garter), and surmounted by a Royal crown. They are fully London hallmarked to the lower section of stem for William Soame in 1733. This would be exciting enough to find. However, it is the addition of the tiny, later script initials above the hallmark which adds another layer of interest. Engraved ‘EA / Fs’ for Ernest Augustus Fidekommiss (entailed [to the estate of ] Ernest Augustus).

These spoons were originally part of the wide ranging British Royal silver collection and were part of the considerable amount housed in Hanover in the Palace of Herrenhausen, then part of the British territory of Hanover.

On the death of King William IV and the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837, the territory had to be split from the British crown, as under Salic law Queen Victoria was barred accession to the Hanoverian throne.

This set in motion very difficult relationships between Queen Victoria and her uncle, the now King of Hanover. His seizure of not only the palace but contents, and the considerable collection of British Royal silver and works of art within. Unthinkable at the time, these tense Royal relationships

almost ended in public lawsuit.

As part of this seizure of the Palace and contents H.R.H Ernest Augustus I Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover added the small, discreet but very telling monogram to the silver. This really was his way of stating his right to the silver and that it now formed part of his collection.

The collection was wide and varied and included European as well as English silver. Perhaps most famously the impressive series of 72 candlesticks. They were delivered over an extended period with the first two dozen delivered on 16th September in 1744. From their original order it was intended to recycle old silver from the Royal Jewel House. To this end, for this commission and others, including the remarkable commission of five eight-light chandeliers after a design by William Kent, it is recorded that ‘a salver, a wine fountain and cistern, pastry dishes, a night lamp and stand, one hundred and twenty plates and dishes, a spittoon, further plates and dishes, tea kettles, a chamber pot, a standish (inkstand), five keys and a warming stand’ were supplied to Behrens with close control taken over the weight and purity of the silver.

Various sets of these candlesticks and other items by Behrens for the Hanoverian Court still survive. An impressive group of table wares and one of the chandeliers can be seen in The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Two others of the chandeliers are within the collection of the National Trust and are displayed in situ at Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire. The silver stayed at the Palace of Herrenhausen until shortly after the Seven Weeks war in 1866 and the Prussian annexation of Hanover. The plate survived intact as it has been hidden in a vault within the Royal palace, despite the palace being looted by Prussian troops. With the family’s deposition from the throne, although allowed to keep the titular title of King of Hanover, they

were also given the title of Dukes of Brunswick. They fled to Penzig, Austria and to the villa of Gmuden, where the plate would latterly be kept.

The collection descended through the family until the death of Ernest Augustus II and was sold by his son Ernest Augustus III in 1924 to the Viennese dealers Gluckselig and to Crichton Brothers of Bond Street London, arguably the most important dealers in antique silver in Europe at the time. It was then split by them with items variously being sold to collectors and institutions alike. To this day, both major institutional and private collections consider items with this provenance amongst the most

important within their collections; not only the fine quality and provenance of the items but the remarkable story they tell. This surely proves that an item as simple as a spoon – or in this case a set of six – can have a remarkable story to tell and not only be witness but be part of history as it happens.

When considered, the royal lineage of these spoons is amazing, irrefutably owned as follows:

King George II, 1727 – 1760

King George III, 1760 – 1820

King George IV, 1820 – 1830

King William IV, 1830 – 1837

H.R.H Ernest Augustus I Duke of Cumberland and King of

Hanover, 1837 – 1851

King George V of Hanover, 1851 – 1878

King Ernest Augustus II of Hanover, 1878 – 1923

King Ernest Augustus III of Hanover, 1923 – 1953

If only such items could talk!