Introduction

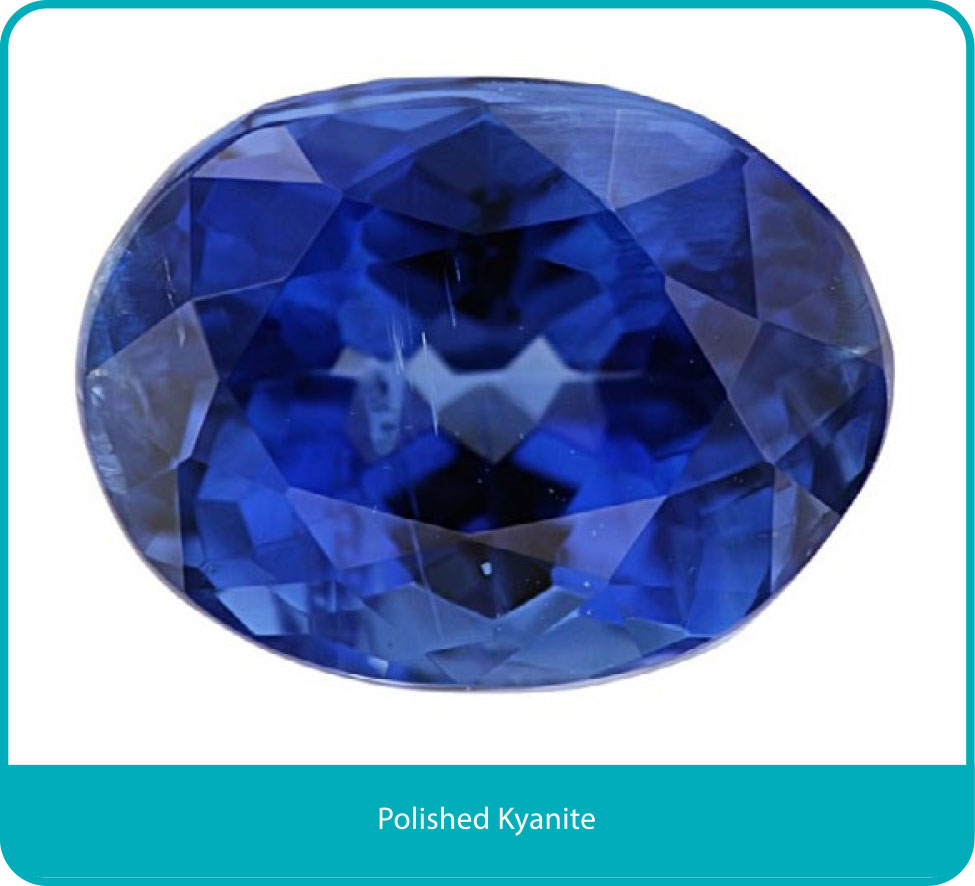

K is for – Kyanite, a gemstone which is more frequently being used in modern jewellery and is a favourite of designers such a Pippa Small. But what is this beautiful blue stone and what do you need to know about caring for it?

Colour

Sometimes mistaken for sapphire, kyanite was named in 1789 by Abraham Gottlieb Werner and is derived from the Greek word ‘kyanos’ which is in reference to its typically blue hue though it can also be found in other colours including green, grey and rarely yellow, pink and orange. A strongly pleochroic material, kyanite is a trichroic stone meaning three distinct colours can be seen depending on orientation though our eyes only allow us to distinguish two at a time. The orange variety often has weak pleochroism. Most material has a ‘glass-like’ vitreous or pearly lustre and is transparent to translucent.

Chemistry and Localities

Kyanite is an aluminium silicate mineral (Al2SiO5) and belongs to the triclinic crystal system, most commonly forming in sprays of blade-like crystals but distinct euhedral crystals can also be found and are highly prized by gem crystal collectors as specimens. Kyanite is the high-pressure preferring polymorph of the minerals Andalusite and Sillimanite, which means that the three minerals have the same chemical composition but different crystal systems. The most significant localities are Kenya, Mozambique, Madagascar and the USA.

Use as a Gemstone

Kyanite is difficult to facet and polish due to its perfect cleavage and differential hardness. When cut parallel to the c-axis (direction of growth), it has a hardness of 4 to 4.5 but when cut perpendicular to the c-axis, it has a hardness of 6 to 7.5. Whilst some material may be relatively free from inclusions, most kyanite seen in jewellery will be included or colourzoned. This is especially true of larger stones. A rare phenomenon called chatoyancy or ‘cat’s-eye’ has been reportedly found in some kyanites when cut en cabochon.

Due to its variable hardness and brittle nature, kyanite is not particularly suitable for wearing in rings or bracelets and a protective collet setting is preferable to minimise damage from wear. It is suitable for other jewellery items such as earrings and pendants which are less likely to encounter wear and tear of the stones.

Care should be taken when cleaning kyanite and they should not be placed in an ultrasonic or steam cleaner. Instead, a soft brush (a baby’s toothbrush is perfect) with some warm soapy water is recommended.

Other Uses

Kyanite is also used in refractory and ceramic products like high-refractory strength porcelain and other porcelains such as dentures and bathroom fixtures. Its resistance to heat also makes it useful in the manufacture of cutting wheels, insulators and abrasives.

Gem Testing

Although it was previously mentioned that kyanite could be visually mistaken for sapphire, gemmological testing easily confirms the identification of these materials. Kyanite has a refractive index of 1.710 to 1.735 whereas sapphire has a refractive index of 1.76 to 1.77. A difference in optical character along with specific gravity testing also distinguishes between the two.

Value

Lower quality, heavily included material can be purchased for a mere few pounds (GBP) per carat but cleaner, higher quality blue stones and rarer coloured kyanites can achieve hundreds of pounds per carat.