Pictures, like small children, prefer consistency of treatment. In the case of caring for paintings and watercolours this means no violent fluctuations in temperature or humidity.

Water damage

If you have a damp room a de-humidifier can bring the relative humidity down around 40%-60%, above this level and there is a possibility of mould growing on surfaces and this can stain the paper on which watercolours, drawings and prints have been worked, irrevocably. Some moisture in the air is good, especially for inlaid furniture and panel pictures. I was in the Pinacoteca in Bologna 40 years ago, where there was about zero relative humidity and the great wooden altarpieces were groaning like ships’ timbers, as they dried out and moved. It is not like that now!

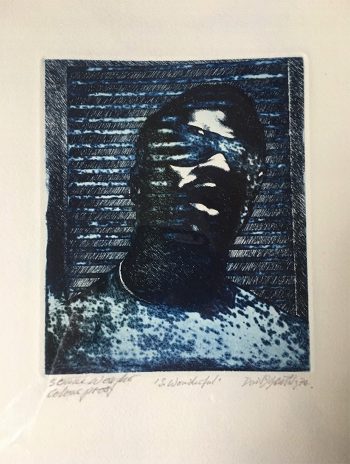

Example of water damage

Where to hang your painting

Hanging paintings above radiators or chimney breasts is to be avoided as the paint layer dries out and becomes brittle and if the painting is on a panel it can warp. The same applies to furniture.

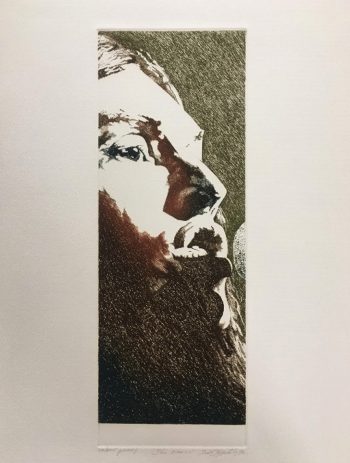

A light-damaged painting

Direct sunlight is a no-no, especially for watercolours. I remember seeing a large pair of watercolours by Turner hanging in a lightwell. They had been there since 1800 when the owner’s forbear had bought them at Christie’s. I tracked the sale and instead of being worth £200,000 (they were obviously very early ones) they were worth about £5,000 as curiosities. All the colour had been bleached out – no blues, no greens, just pale pink and brown smudges. What a tragedy!

Whether light travels in waves or pulses, it equals heat, and this will damage anything subjected to it. Ultraviolet inhibiting strips can be put on windows, but they are only about 60% effective and should not be exclusively relied upon. Old-fashioned velvet curtains, with brass rods stretched through the bottoms are an ideal way of protecting watercolours in daytime and can be turned back at night.

Artificial lighting can be harmful too, although it lacks the sun’s power, so low energy bulbs should be used and try to avoid picture lights on brass arms attached to the frame of an oil painting. They are too close to the surface of the painting and can cause stress to an old carved and gilded frame.

Cleaning of paintings

The cleaning of all paintings must be left to well-trained professional conservators. It is a highly complex procedure requiring in-depth knowledge of chemistry. Never use a damp cloth to clean the gilding on a frame. If it is water-based gilding, as opposed to oil, it will dissolve. A feather duster is preferable to a cloth duster as it is less likely to snag the carving and pull it off. You can dust the surface of an oil painting, very gently, with a cloth duster.

Lastly, never dust the glass on a pastel, it can cause static electricity to build up and the pastel (powdery chalk), which was never treated with a fixature in the 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries, will jump off the paper and adhere to the inside of the glass!

Damage caused by fly faeces

Some things you just must live with, such as houseflies whose poo can stain an oil painting and can only be removed with a scalpel (don’t try this yourself!). Thunderflies, in high summer, can find their way under the tightest-fitting glass and litter the surface of a watercolour or drawing. Wait until autumn and take the backing off the work on paper, dust them out and reseal.

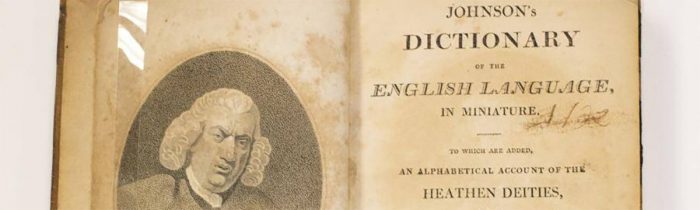

An example of damage caused by silverfish

Silverfish are a menace. If they get into a Victorian watercolour, they can munch their way through the pigments, which have been impregnated with gum Arabic, (the substance that Osama Bin Laden’s family fortune was based on), leaving patches of bald paper. Try to keep on top of silverfish by regular hoovering.

Another example of damage caused by silverfish

If you do have the misfortune to have water or fire damage or a painting falls off the wall, it makes sense to have a good photographic record of it, as this could help a conservator restore it and a loss adjuster assess a claim.