It’s 1915 and the First World War is raging. Winston Churchill, now aged forty, was in the thick of the fighting, leading his men at Ypres. It was while resting behind enemy lines at Ploegsteert, nicknamed ‘Plug Street’ by the Tommies, that he first picked up a brush to paint for the first time. His reasons for doing so are most eloquently expressed by Churchill himself in the introduction to his book ‘Painting as a Pastime’ first published in 1947.

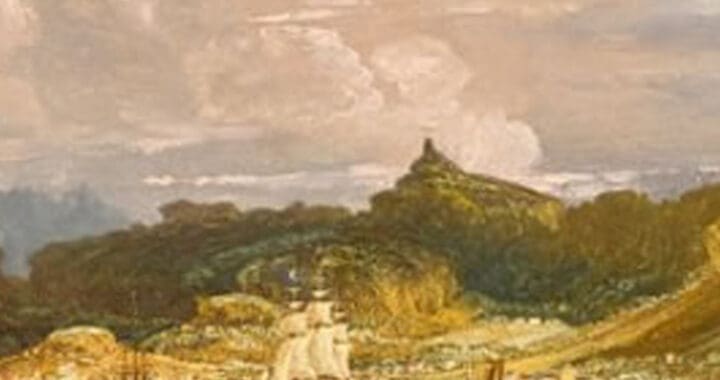

Plug Street, 1915. Oil on canvas. 51 x 60 cm

Painted during WW1 while Churchill was resting with his men behind the battle lines at Ploegsteert near the front at Ypres.

In the National Trust collection at Churchill’s home , Chartwell, Kent

“Happy are the painters, for they shall not be lonely. Light and colour, peace and hope, will keep them company to the end, or almost to the end, of the day. To have reached the age of forty without ever handling a brush or fiddling with a pencil, to have regarded with mature eye the painting of pictures of any kind as a mystery, to have stood agape before the chalk of the pavement artist, and then suddenly to find oneself plunged in the middle of a new and intense form of interest and action with paints and palettes and canvases, and not to be discouraged by results, is an astonishing and enriching experience. I hope it may be shared by others. I should be glad if these lines induced others to try the experiment which I have tried, and if some at least were to find themselves dowered with an absorbing new amusement delightful to themselves, and at any rate not violently harmful to man or beast.”

THE LOUP RIVER, ALPES MARITIMES, 1930. Oil on canvas. 20 1/8×24 (51·5×61). Presented by the artist 1955. Exh: R.A., 1947 (174); R.A. Diploma Gallery, March–August 1959.

The picture was painted in 1930, and the site lies about five hundred yards from where the main Cagnes to Grasse road crosses the river.

It was one of the two pictures Churchill exhibited at the R.A. in 1947 and were submitted to the Selection Committee under the name ‘David Winter’.

Churchill soon found that watercolours were not his ideal medium, and instead switched to the more robust medium of oil paint – as ‘you can more easily paint over your mistakes’. Early encouragement came from an amateur prize he won for “Winter Sunshine, Chartwell,” a bright reflection of his Kentish home. Also, under the pseudonym Charles Morin, he sent five paintings to be exhibited at the Paris Salon in the 1920s, where four were sold for £30 each. However, making money was not the incentive, then or ever. It was simply the sheer delight of painting that accounted for Churchill’s devotion.

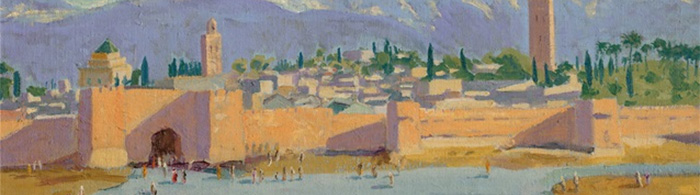

Tower of the Koutoubia Mosque. Signed with initials ‘W.S.C.’ (lower right). Oil on canvas. 45.7 x 61 cm.

The world auction record holder for Churchill sold on behalf Angelina Joli for £8,285,000 in January 2021 the only painting Churchill completed during WW2 and gifted to President Roosevelt, probably the most historically Important picture by Churchill.

He readily received tuition and guidance from some of the leading artists of the day such as Sir John Lavery, Sir William Nicholson and Walter Richard Sickert. This led, in 1947, to the then president of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings, suggesting Churchill submit two works to the annual Summer Exhibition. Churchill was eventually persuaded, on the proviso that they be submitted under the pseudonym of David Winter. Both pictures were accepted, with one being acquired later for the National Collection by the Tate. A few years later during the first post-war Royal Academy Dinner in 1949, Churchill was made an Honorary Academician (Hon, R.A), the first and so far, only person to be awarded this honour.

JUG WITH BOTTLES, signed W.S.C. (lower right). Oil on canvas board. Unframed: 51 by 35.5cm.; 20 by 14in.

Painted at Chartwell sold in Nov 2020 for £983,000

Churchill had a true craftsman’s dedication to his art and readily accepted the advice to visit Avignon and later the Cote d’Azur where he discovered artists who worshipped at the throne of Cezanne. He also acknowledged the inspiration he derived from his many visits to Marrakech, Morocco.

MIMIZAN, signed with initials. Oil on canvas, 56.5 by 36cm.; 22¼ by 14in. Executed circa the 1920s

Image of painting by Winston Churchill. Sold June 20128 for £430,000

Gifted by the Artist to Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein in 1950

Churchill sought and found tranquillity in his art. His much-quoted words, summing up his expectations of celestial bliss; “When I get to heaven, I mean to spend a considerable portion of my first million years in painting, and so get to the bottom of the subject…”

THE SCUOLA DI SAN MARCO VENICE, signed with initials. Oil on canvas, 50.5 by 61cm.; 20 by 24in. Executed in 1951.

Churchill loved Venice, he spent his honeymoon there in 1908, this picture was painted on a family holiday at the Lido in 1951.

Sold Nov 2015 for £500,000

By far the best and most enjoyable way to get to know the man and his art is to visit his beloved Chartwell in Kent. Now owned and run by the National Trust, Churchill’s paintings and artefacts are all around the house, but for me the revelation is the Garden studio which is full of Churchill’s paintings, hung corner to corner almost, with his paints, brushes and easel all set out as if he were returning shortly… not to be missed!

View of Blenheim Palace through the branches of a cedar. Oil on canvas. 61 x 51 cm

A view of Churchill’s childhood home painted in 1920 and gifted to Churchill’s daughter Mary Soames, and sold from her estate collection sale in December 2014

for £566,000

RELATED ARTICLES

Sir Winston Churchill

African, Modern and Contemporary Art

Artists to Watch in 2021

Modern British Sculpture Sleeper

Bridget Riley

Laura Knight

Mary Fedden

George Condo

David Hockney

MORE ARTICLES

Modern and Contemporary Art and Sculpture

Old Master Paintings

Jewellery

Watches

Books and Manuscripts and Written Material

Objects of Virtue

Clothing and Accessories

Insurance Articles

Furniture

Arms and Militaria

Wine and Whisky

Miscellaneous Articles

The pick of the bunch were definitely at Christie’s where the evening sale made £45M as opposed to Sotheby’s comparatively paltry £17.2M. In fact, the tiny pen and ink study of the Head of a Bear by Leonardo da Vinci, which sold at Christies for £8.857M made half the whole of the Sotheby’s evening sale on it’s own. My stand-out lots at Christie’s were first the exquisite Music Lesson by Frans van Mieris, on panel made out from a small arched-top painting to a larger rectangle by the artist himself, which, at £3.5M indicated that no-one was put off by the alteration to its shape. Second was the magnificent large View of Verona by Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, which took £10.575M. My third choice was the very rare canvas of Saint Andrew by the French follower of Caravaggio, Georges de la Tour.

The pick of the bunch were definitely at Christie’s where the evening sale made £45M as opposed to Sotheby’s comparatively paltry £17.2M. In fact, the tiny pen and ink study of the Head of a Bear by Leonardo da Vinci, which sold at Christies for £8.857M made half the whole of the Sotheby’s evening sale on it’s own. My stand-out lots at Christie’s were first the exquisite Music Lesson by Frans van Mieris, on panel made out from a small arched-top painting to a larger rectangle by the artist himself, which, at £3.5M indicated that no-one was put off by the alteration to its shape. Second was the magnificent large View of Verona by Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, which took £10.575M. My third choice was the very rare canvas of Saint Andrew by the French follower of Caravaggio, Georges de la Tour.  This made a very respectable £4M. I don’t know how many paintings by this rare master are still in private hands, but it will be a tiny number. The only disappointment to my mind was the beautiful Lawrence portrait of Richard Meade, which sold for £598K, within the estimate but not a true reflection of its worth.

This made a very respectable £4M. I don’t know how many paintings by this rare master are still in private hands, but it will be a tiny number. The only disappointment to my mind was the beautiful Lawrence portrait of Richard Meade, which sold for £598K, within the estimate but not a true reflection of its worth.