It’s fantastic to see so many new artists’ work coming to the fore all over the globe, and how the role of buying and selling fine art is evolving to attract new audiences.

Attracting new buyers

Somehow the art world has managed to fast forward thanks to technological advances brought in as a matter of necessity during the pandemic, removing many or all of the old barriers that were putting first time buyers off auctions, or more positively pulling them in!

How many online bidders at Christie’s?

As an auctions career ‘lifer’ myself, I have always believed it’s a numbers game. The more active bidders you have in any auction the better it will perform.

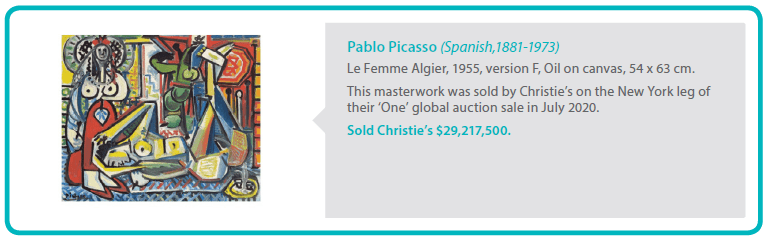

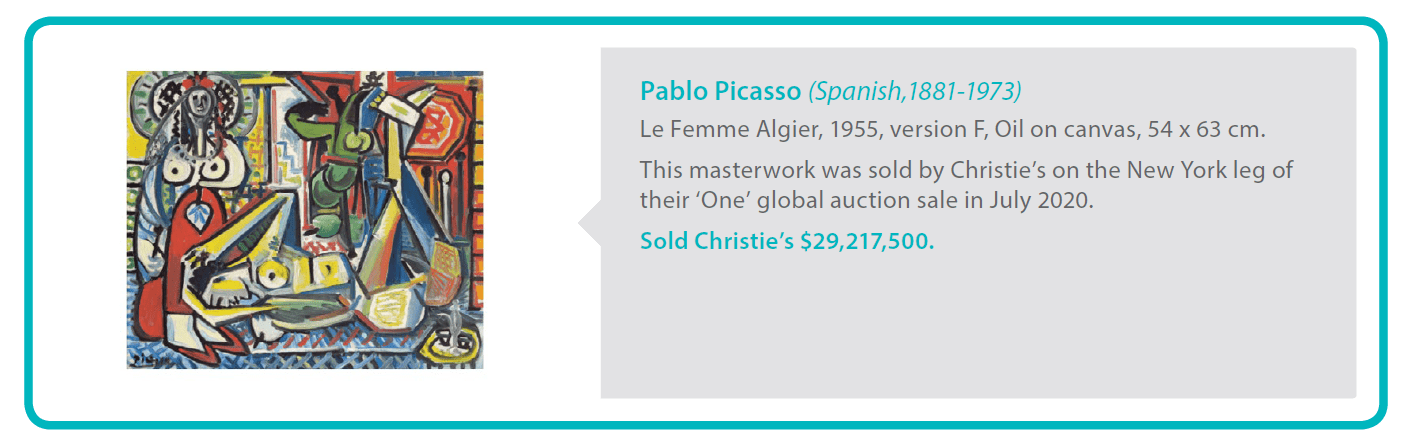

Thanks to technology – Christie’s managed, in a heartbeat, to get from an average 8-1,200 hundred online bidders to 50,000, which is what happened at their global ‘one’ event in 2020. There were so many bidders that when I tried logging on, it bounced me out!

Is online bidding here to stay?

Although the online affect could diminish as the post-pandemic era progresses, thousands of new collectors and buyers are now hooked as auction houses have demystified the process of an auction.

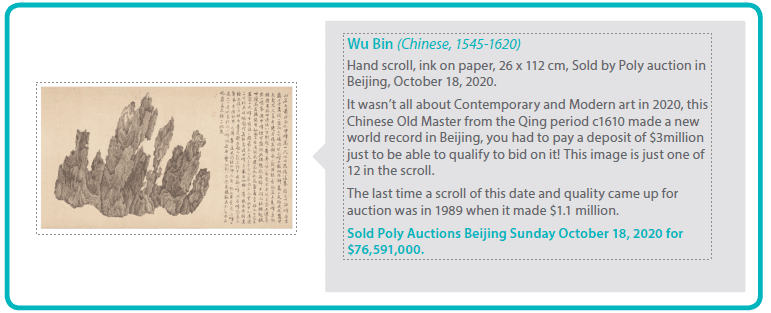

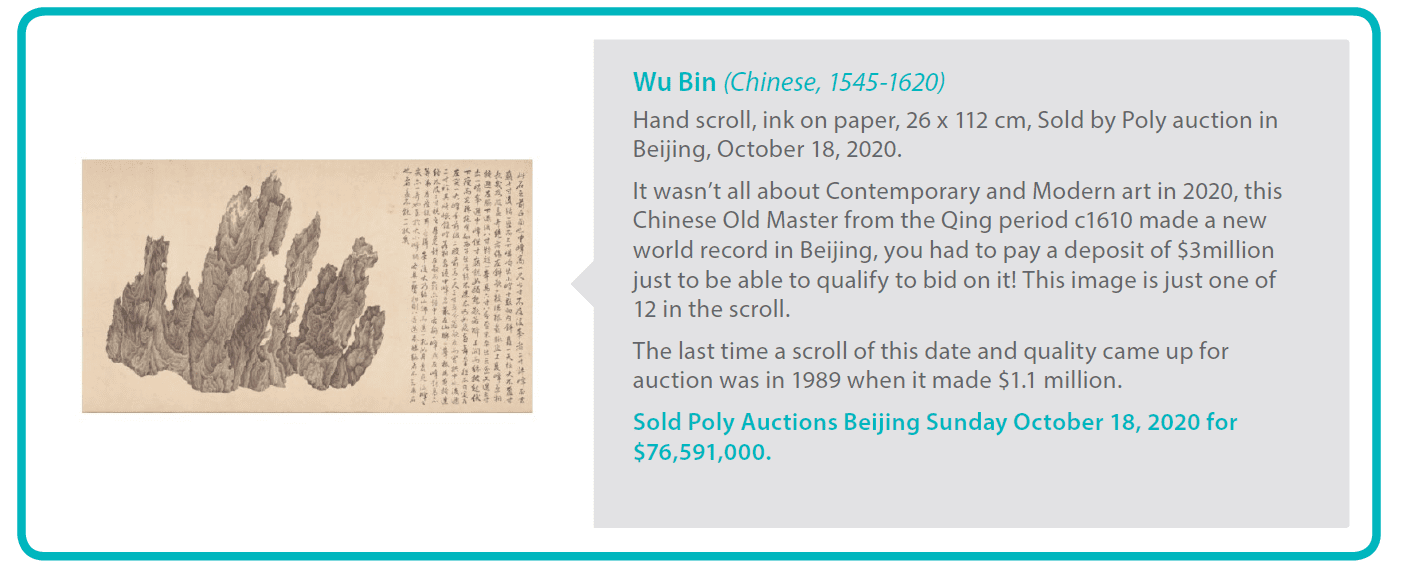

I can see that it’s happened by accident and not design. We’re entering into a new era with contemporary art auctions still growing, Old Masters are doing well especially Prints. Jewellery, Watches and Design are still strong but the focus is heavily on masterworks or special pieces.

How are auction houses evolving?

New ways of selling are now starting to emerge thanks to the new owner of Sotheby’s Patrick Drahi who bought the business pre-lockdown. He has quite logically seen his brand is much more able to penetrate into new areas. Yes Sotheby’s is an auction house but it’s also a luxury shop selling branded goods.

Christie’s ‘One’ live auction held all one day July 10th 2020, it was one very long auction broadcast from four locations starting in Hong Kong,

then switching seamlessly to Paris, London and finally New York

New auctioning ideas are appearing all the time with the most recent being the Las Vegas MGM Grand live auction of works by Picasso from the Casino Picasso Dining room this October. Only 11 pictures, all by Picasso were in the auction, and raised a staggering total of $110,000,000 from what is only a selection of works the Casino owns.

The next day luxury items, sneakers, handbags, watches and the like all did equally well in a smaller MGM Casino downtown. This was truly an event auction and I think it will set the trend for the years to come.

I think we can all be encouraged by the fact that more people than ever before are taking an active interest in auctions both as buyers and sellers.

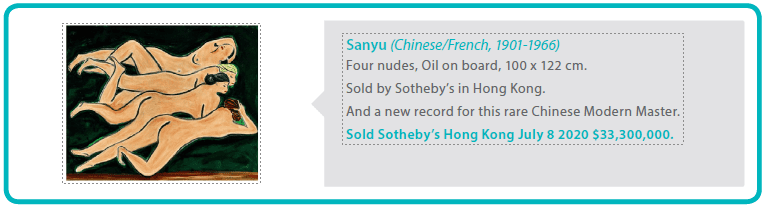

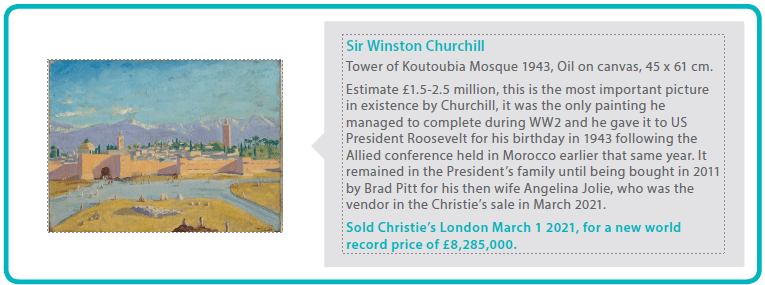

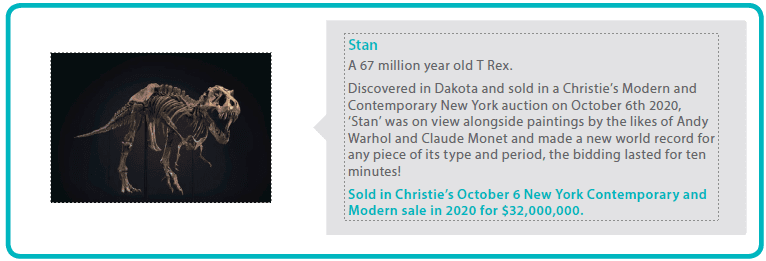

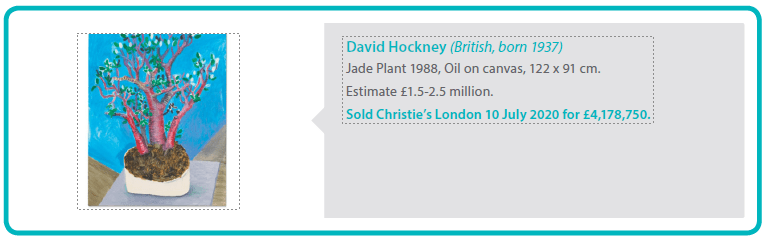

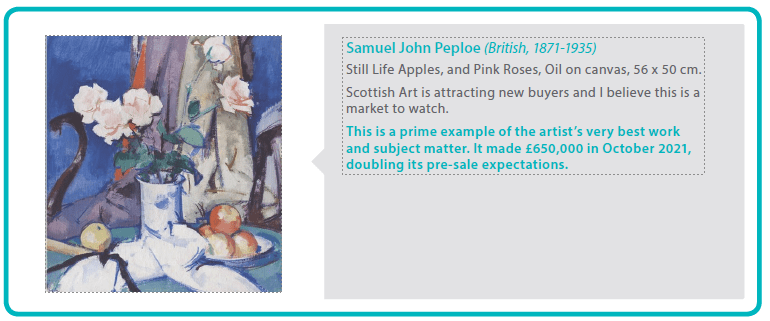

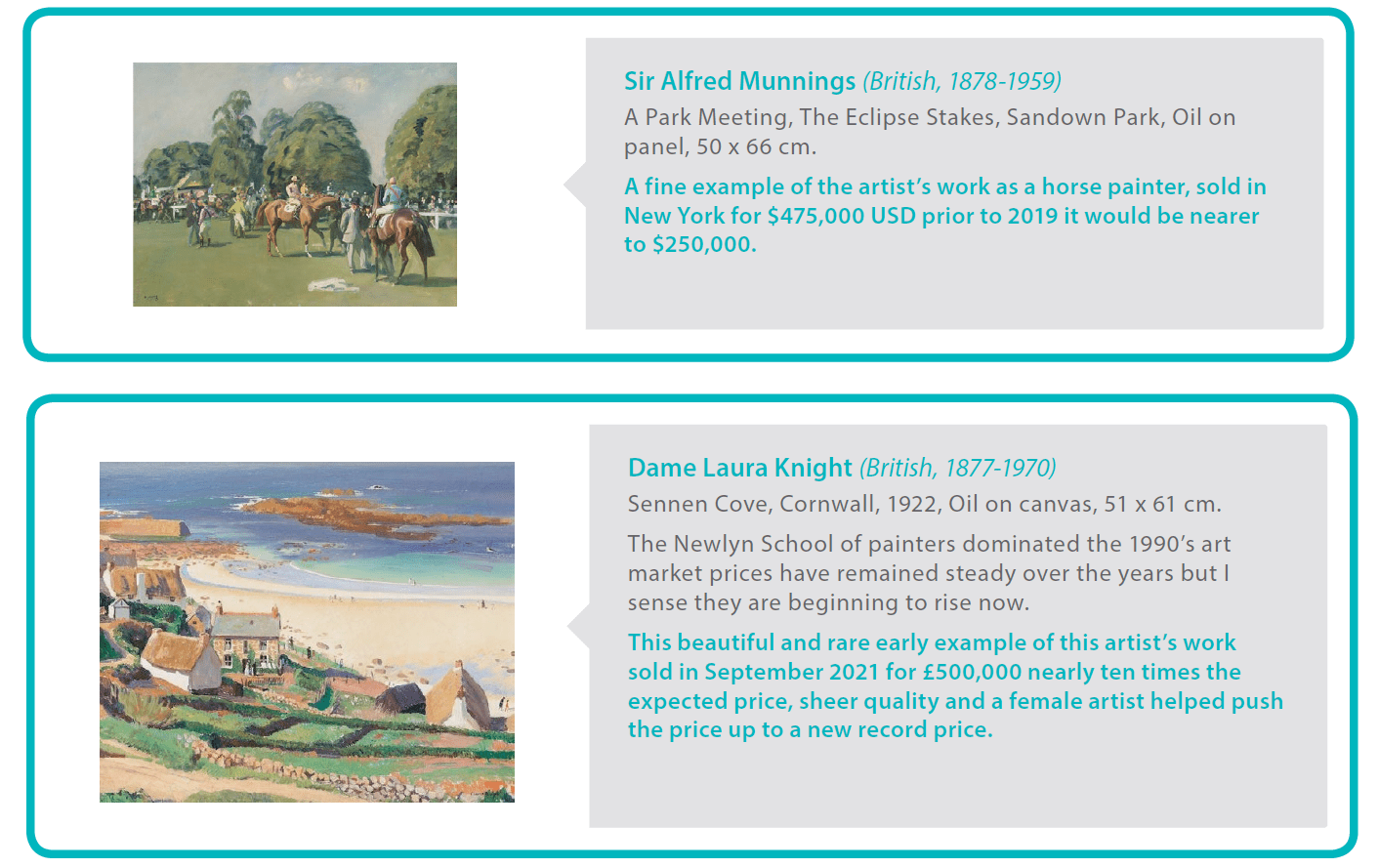

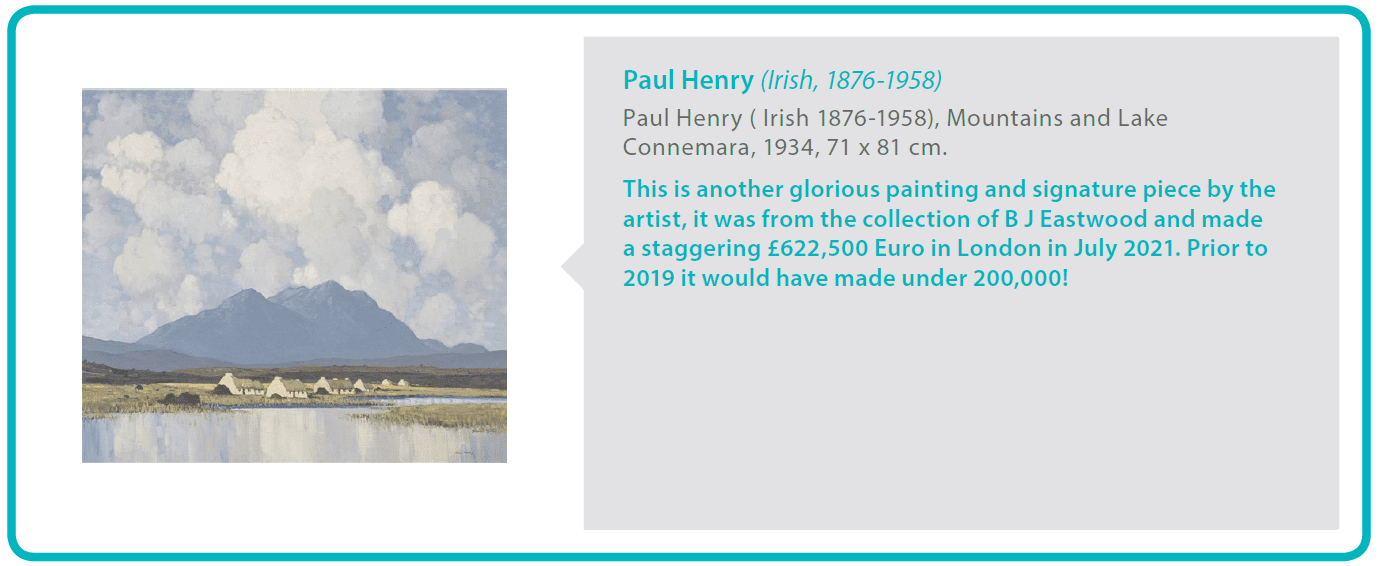

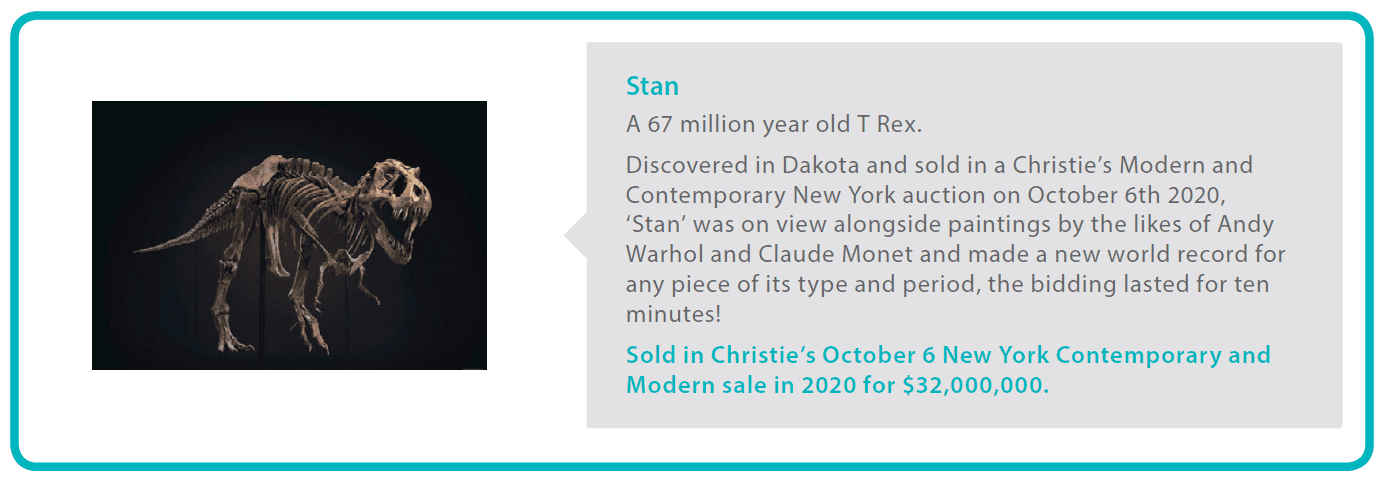

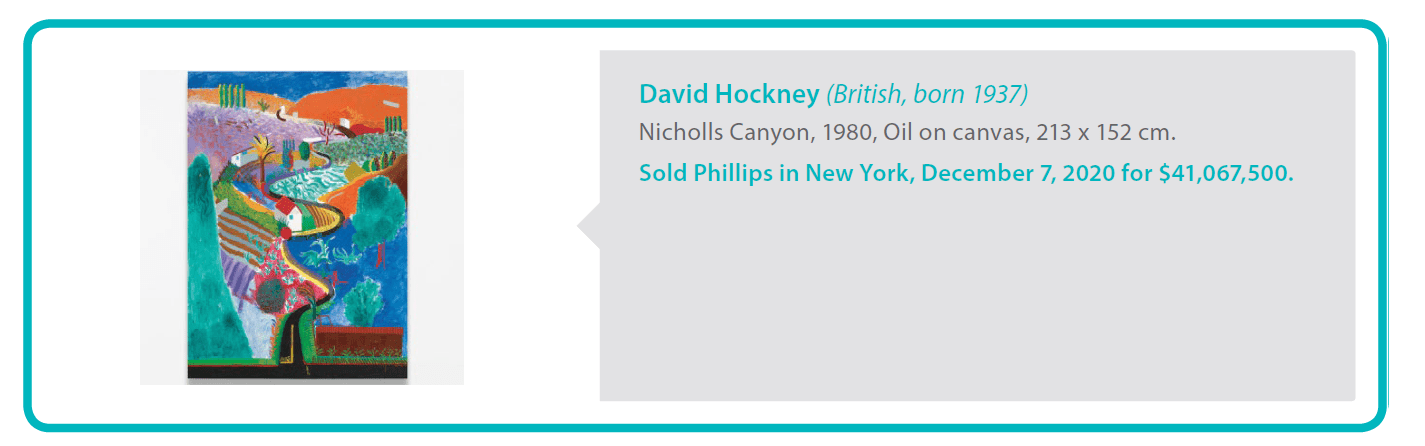

Here are some fine art pieces sold highlighting what an extraordinary year 2021 has been.

In 1974 I worked for Alex Postan Fine Art and was entrusted with getting publicity for the show of etchings, which included watercolours and acrylics as well as prints. It was the easiest job I have ever had. Marina Vaizey wrote a half page review of it in The Telegraph, Bill Packer, a half page in the Financial Times and it was in the list of the 10 best things to do this Christmas in London in the Daily Express. Rod Stewart came to the private view. Oxtoby went on to exhibit with the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street in the 70s where the private views would sell out. Elton John bought Oxtoby’s canvases in vast numbers, for prices that were somewhere between Hockney and Picasso. He is still with the Redfern.

In 1974 I worked for Alex Postan Fine Art and was entrusted with getting publicity for the show of etchings, which included watercolours and acrylics as well as prints. It was the easiest job I have ever had. Marina Vaizey wrote a half page review of it in The Telegraph, Bill Packer, a half page in the Financial Times and it was in the list of the 10 best things to do this Christmas in London in the Daily Express. Rod Stewart came to the private view. Oxtoby went on to exhibit with the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street in the 70s where the private views would sell out. Elton John bought Oxtoby’s canvases in vast numbers, for prices that were somewhere between Hockney and Picasso. He is still with the Redfern.