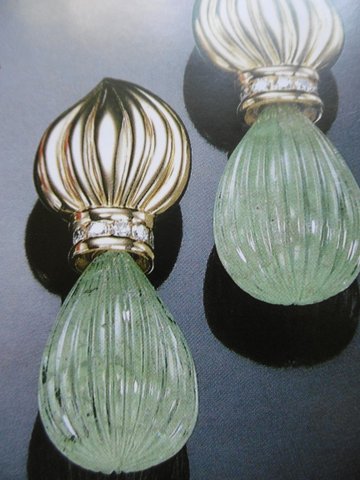

These luscious green stones are first mentioned around 3500 BC – and were treasured for their beauty and have over the years been attributed with bringing good health, love and romance and were considered the gem most close to the Deities. An early believer and emerald hoarder was Cleopatra who started two emerald mines in her native Egypt on the slopes of Mount Smaragous (from which we eventually get the word ‘emerald’). The Romans preferred them to diamonds and in the 17th century the Indian Moguls carved prayers and blessings on large flat cut emeralds.

A fine emerald exhibiting all the required qualities, and is in addition, over 12 carat

After the Egyptian mines were exhausted smaller deposits were exploited in India and Austria, but it was in the mid 1500’s when Spain started colonising South America and Columbia in particular, that they became far more readily available and they were and still are considered to be the best real gem quality stones. Columbia alone supplies about 60% of the world’s supply but since the 1950’s small quantity of good quality stones has been coming from Brazil, Zambia and the very sought after Sandawana emeralds from Zimbabwe. Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Madagascar also have reasonable reserves but supply from all these countries is spasmodic due to political grief and wars.

Emerald of a poor colour and heavily flawed stone

Their comparative rarity has maintained their popularity over the years and in 2011 Elizabeth Taylor’s emerald collection was sold for about $25 million and more recently an 18 carat emerald and diamond ring belonging to Angelina Jolie sold for over $5.5 million – setting a record of over $300,000 per carat.

So what are emeralds? They are members of the Beryl family which includes the pale blue Aquamarine and the pale pink Morganite amongst others. They are a relatively ‘soft’ stone measuring 7.5 on the gem hardness scale as opposed to a diamond at 10, so they fracture, chip and scratch quite readily. With a diamond it is both good colour and clarity that enhance value – with emerald it is mostly about colour as it is virtually unheard of to find a totally ‘flawless’ stone. The most prized emeralds are those with a rich dark to medium green tone and preferably with good even ‘saturation’ of colour and translucence throughout the stone.

The palest green that would still be classified as emerald

The first photograph shows a fine emerald exhibiting all the required qualities and is in addition a whopper at over 12 carat. The second photograph shows a poor colour and heavily flawed stone, and the third photograph shows the palest green that would still be classified as emerald.

In the fourth photograph the stone on the left is about 3 carats and good colour and decent clarity, the one on the right is over 4 carats and pretty pale and noticeably flawed. The ring on the left fetched twice as much as the other one at auction recently. That’s the difference, both visually and value wise between a ‘good un’ and a ‘bad un’.

Left: about 3 carats and good colour and decent clarity

Right: over 4 carats and pretty pale and noticeably flawed.

Pale green stones do not achieve the title of emerald and are called green beryls and are of relatively small value. For centuries, surface scratches and fissures which nearly all emeralds suffer have been ‘oiled’ which fills the cracks and because the oil is colourless it ‘evens up’ the colour. More recently polymers and resin have been used instead of oils and because they are often coloured green they are considered to represent unfair and unethical enhancement. This is described as ‘modern’ treatment and should be avoided. The long established methods are described as ‘traditional’ and as long as it is not excessive, is nowadays acceptable. Because of this, any proposed purchase of a serious emerald should only be considered if the stone has a laboratory certificate grading the extent and type of enhancement. There are generally four grades of enhancement – none (very rare), insignificant (desirable), minor (acceptable) and moderate )just about ok)) and significant (to be avoided).

Internal inclusions, called ‘jardins’ in the trade, are expected and accepted as normal. They range from feathery/mossy looking gas or liquid filled ones to internal fractures and fissures. The range and type of inclusion can be interpreted by a laboratory test and they can ascertain from which area and country the stone originates. The techniques now available to remove or reduce inclusions in a diamond involving laser beams and high temperature treatments cannot be used on an emerald due to its comparative softness and different crystal structure, so whatever defects get moulded in to the emerald at the time of formation remain with it.

A fine quality and colour emerald of decent size – say 3 carats and over – is far rarer than a quality diamond of the same size, so, in my opinion, should be of higher value. That’s not the case, however, and although Angelina Jolie’s stone fetch over $300,000 per carat, there are plenty of diamonds around priced at over $500,000 per carat. £5000 per carat would buy you on the retail front a very presentable emerald but the same carat price would get you a diamond pretty far down the scale in colour and clarity.

So with that in mind, could an emerald be a good investment? As with most categories of speculative investment always go for the best you can afford – go for colour firstly, clarity secondly and size thirdly, and bearing in mind its comparative fragility, treat it gently and have the stone and its mount checked by a jeweller regularly.