With the final phase of Brexit looming ever nearer and no defined solution yet emerging, all sectors of the UK economy are thinking ahead nervously to discern what effect this messy divorce with Europe will mean for them – this is no less the case than with the UK Art Market.

The British art and antiques market is the third largest of its kind in the world with a global share of 22%, and a 65% share of the European Union’s art and antiques market. It represents total sales of over £10 billion annually and it is comprised of 7,850 businesses, providing direct employment for 41,420. The British art market is defined as being a ‘entrepot market’ in that it serves as a conduit for sales of artwork which are often imported into the UK solely to be sold here and then re-exported out of the country – one only has to look at the main Impressionist, Contemporary and Russian sales to demonstrate this, together with the top tier of international art fairs such as Frieze, Frieze Masters, Masterpiece and PAD. The Art Market is therefore particularly active and dependent upon cross-border trade.

Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, originally predicted that Britain would probably suffer a moderate Post Brexit downturn in the economy; this prediction now seems to be highly conservative with current estimates ranging from post-Apocalyptic melt down to a simple short-term realignment of the UK economy.

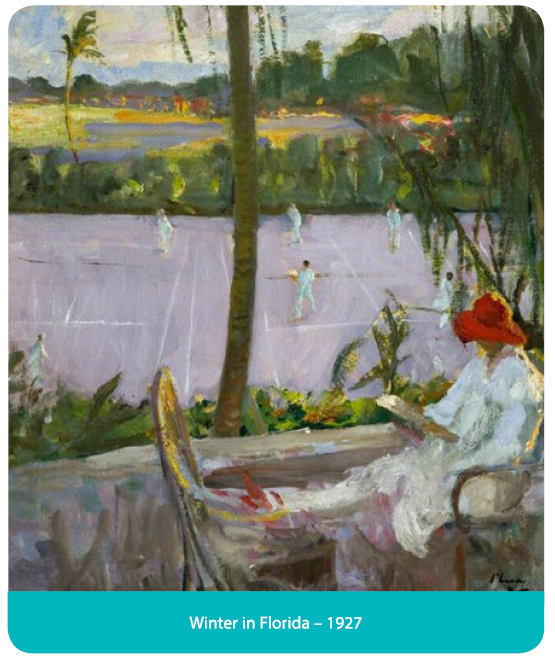

What is certain is that the strength of the Pound will continue to fall until clarity has finally emerged. This, in itself, is not universally bad for the UK Art Market as it makes purchasing UK goods cheaper for foreign investors – UK collectors, however, find it more expensive to buy internationally in the short term. The one category of high-value secondary art that will be affected negatively post-Brexit is art where the primary market is British buyers. Consignors may choose to wait for the Pound to stabilize and uncertainty to decline. The obvious category is Modern British Art of the 20th century. It is also possible that he Old Master market will be similarly hit in the short term as UK buyers make up a small but significant portion of the collector base.

Having said this, it is not all doom and gloom for the UK market, typically UK collectors only represent between 10% of the total turnover at the main London Auctions – this figure includes purchases by foreigners living in the UK. Many Eastern European and Middle Eastern buyers will still prefer London over New York. Although it is true that some consignors may prefer to offer their works in New York rather than in London.

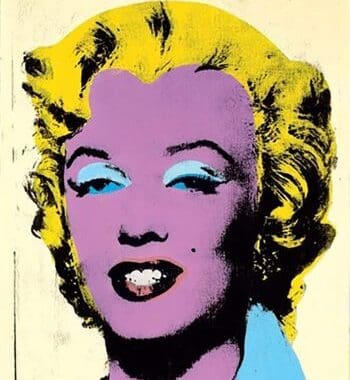

Post Brexit, London may indeed even emerge to be a stronger auction market compared to Paris and the rest of Europe as it should be free of EU regulations, particularly the Artist’s Resale Rights levy (ARR). This had final implementation in the U.K. in 2012, after six years of strong resistance by the government. ARR entitles creators of original works of art to a royalty each time a work is resold through an auction house or dealer for more than €1,000. It is levied at 4% on sales between €1,000 and €50,000, declining to 0.25% on sales at more than €500,000. ARR continues for 70 years after the artist’s death.

ARR has put the U.K. at a distinct disadvantage for art sales compared to dealers and auction houses in New York, Switzerland, or Hong Kong, which do not levy the charge. It has been suggested that the UK’s global art market share in post-war and contemporary (the sector most affected by ARR) fell from 35% to 15% from 2008 to 2013, due mainly to the implementation of ARR in 2006.

Brexit or not, London will continue to be the preferred choice of residence for international Non-Dom Billionaires, many of whom are major art purchasers, and it is doubtful that a new government will do nothing to make the city or its tax advantages less attractive. London is a major centre for professional and financial services because of the rule of law, and attractive because of its cultural life and quality of infrastructure. The Brexit vote did not change any of this.

The uncertainty surrounding the whole Brexit negotiations has led to a great deal of money being transferred around the money markets to gold, US Treasuries and similar investments deemed a safe store of wealth. Historically, when financial markets are in turmoil, art is seen as a good store of long-term value, and a hedge against inflation and changes in the relative value of currencies. For iconic works, there’s a chance to to peg the purchase price against the future value of the US Dollar. The new financial fragility of the EU means that investors will be concerned about high-debt, high-risk member countries—notably Greece and Portugal, but also Spain and Italy. Borrowing for art purchases against assets in these countries may become more problematic and expensive so it is reasonable to expect that these national art markets will experience a downturn and will languish for a while.

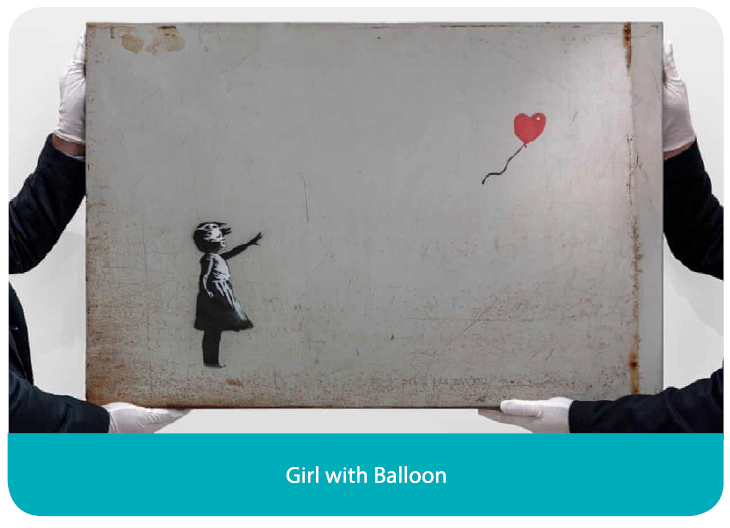

In periods of uncertainly such as Brexit, art investors tend to moderate risk by investing in works by Blue Chip artists and more established genres rather than emerging artists since Blue-Chip artist are believed to be safer stores of value, even if the upside profit potential is less. Undoubtedly this will strengthen the high-end Impressionist and Modern markets, which are already the main players of the total market. This same trend will no doubt be experienced at the top end of the Jewellery and collectors watch markets. There is a consensus in the art market that this ‘flight to the better-known’ will be the case at least over the next year or two.

In conclusion, as with everything surrounding Brexit, no certainly exists about how it will play out and the affect it will have on the UK Art and Antiques market – but in fairness, why would we expect there to be certainly following the messiest and most expensive divorce in world history? One thing is clear, in the medium to long term the Art Market will survive and adapt to any and all challenges thrown at it, but in the short term the domestic market will undoubtedly show signs of significant market contraction – but this, in itself, will potentially create new investing opportunities for collectors in the medium term.

As ever, it is the top end of the market which will weather the storm best with top examples by established artists attracting attention and achieving strong prices as investors diversify into these Blue-Chip works. Paradoxically, the strong prices that this alternative investing produce will no doubt inadvertently do much to help bolster global confidence in the art market in the medium to long-term.

Call us today to enquire about an appointment on 01883 722736 or email [email protected] or visit our website www.doerrvaluations.co.uk