Next time you’re watching the Antiques Roadshow, look carefully to see what each of the different specialists do when they first examine a new item.

The jewellery specialists will get out their ‘loop’ (a small high magnification eye glass) and examine the setting, the stone its colour, light reflection, hallmarks and all the other little details of interest to them; the furniture specialists will crouch down on hands and knees to look underneath or pull out the drawers to rummage inside; the ceramic specialist will pick up the piece, turn it upside down and go straight for the base to look for marks and stamps and other clues.

The picture specialists have a similar routine. First a glance at the front and then flip it over to look at the back (size allowing). To the uninitiated it may look like they have hardly glanced at the front. So, what are picture specialists looking for? Well, there could be a whole host of things back there such as: if a picture has been re-framed there might be a sticker or a note left by the framer saying what was done and when. In some cases, it may have been exhibited and there may be exhibition labels pasted on the back of the picture. As dates and locations are usually included, this can help lead to identifying whether or not it is a more or less important work. It may have been bought from a commercial gallery and the quality or value may depend on the gallery it came from. There could have been restoration work carried out on the picture and or notes or labels that may give a hint or indication of where and it when it might have been repaired.

I have often heard the phrase ‘it’s got a very good back’ said about a picture with lots of labels. Certainly something attached to the back of a picture will rarely be removed once there, so it often feels like walking through history when looking at the back of a well labelled picture. It probably doesn’t make any sense if you’re not used to it, but it makes perfect sense if you spend your days looking at pictures. I have even seen specialists look at a photograph of a picture and then out of habit, turn the snap over to look at the back for anything interesting!

I thought it might be helpful just to share a few examples of the backs (and fronts) of some pictures and works on paper that I have seen myself. I also try to explain a little bit more about what I’m looking for, what we are seeing and what conclusions if any, we are able to draw.

L S Lowry (British, 1887-1976)

Children Walking up steps

Oil on board, 25 x 35 cm

Estimate, £150-250,000

From the Artist’s estate

Not signed or dated

Sold £137,000, March ‘21

Reverse of Children Walking up steps

Showing top left exhibition label for Crane Kalman London top left. Bottom centre, loan label for The Lowry Salford

L S Lowry (British, 1887-1976)

Broken Shop Window, 1950

Signed, Pastel, 27 x 37 cm

Estimate £35-55,000

Sold £50,000, March ‘21

Backboard of Broken Shop Window; the green label says NAN, code for Christies Cheshire office, and has Christie’s London address, it shows the work was consigned for sale from an owner in or near Cheshire. In white chalk a previous Christie’s sale date, lot 301 8/Jun/90. Black stencil KKS69, this is unique to Christies, London

Victor Pasmore ( British, 1908-1998)

Abstract, 1951-52, 68 x 83 cm, Oil on board

Estimate £60-80,000

Sold £72,750, Nov ‘20

Photo showing the back of above picture

Magnification of labels on the back see this label for an exhibition at a Jonathan Clark’s London Gallery…. No date probably circa 1990- 2000

Owner’s own label, Sir Martyn Becket’s

Carriers label name on label

Rob Oakden

Not significant

Arthur Tooth, a major London gallery label date, circa 1950’s stock no Cl 686

Arts Council 1980 exhibition label catalogue no 22

David Bomberg ( British, 1890-1957)

Old City and Cathedral, Ronda. 1935, signed lower left, oil on canvas, 64 x 76 cm

£400-600,000

Provenance Asa Lingard, Bradford

Sold £790,750

View of the back of Old City and Cathedral, Ronda, it’s all very original with its original canvas no labels evident so look for any writing on the canvas or wooden stretcher

Spotted some writing top left hand corneron the wood , it says ‘ Ronda, David Bomberg, Spain 1935. Possibly the artist’s hand writing or maybe a previous owner?

More writing top centre , it says ‘Richard Cork says Cuenca‘.

Richard Cork is the authority on Bomberg. This is in biro circa 1980’s so not the artist. Cork changed his mind to Ronda near Malaga.

Centre right, ‘Property of Mrs Nimmo‘ a previous owner again in biro so not Bomberg.

William Roberts (British, 1895-1980)

Women playing with Cats

1919, Signed. Pen ink and watercolour, 29 x 20 cm

£150-250,000

Sold £325,250, Nov ‘20

Back of Women playing with Cats; a great looking back.

Top a label for a show at Tate Britain in 1956, catalogue no 186, it then toured the UK.

Also showing the owners name at the time, Michael Tachmindji.

Hamet Gallery label, Feb 1971, very well known and respected gallery, sold by them to another owner. Arts Council label, they organised the Tate Show and its tour around the UK.

The cut out in the backboard shows the title inscribed on the back of the work itself, written by the artist ‘Women Playing with cats’

Ben Nicholson (British, 1894-1982)

Two Forms

Oil on board, 23.8 x 21.6 cm

Estimate £70-100,000

Sold June ‘18, £193,750

Back of Two Forms. See shipping label and owners name Mr Wright Luddington, who bought the work at the Lefevre Gallery London. See Lefevre gallery label underneath. See writing in pencil top centre, Two Forms, Ben Nicholson 1947, this is all the artist’s writing.

RELATED ARTICLES

The Back of Pictures

Patrick Heron

LS Lowry

Modern British Sculpture

Henry Moore Market

The Art Market and Brexit

Andy Warhol

MORE ARTICLES

Modern Art and Sculpture

Contemporary Art and Sculpture

Old Master Paintings

Jewellery

Watches

Books, Manuscripts and Written Material

Objects of Virtue

Clothing and Accessories

Insurance Articles

Furniture

Arms and Militaria

Wine and Whisky

Miscellaneous Articles

In 1974 I worked for Alex Postan Fine Art and was entrusted with getting publicity for the show of etchings, which included watercolours and acrylics as well as prints. It was the easiest job I have ever had. Marina Vaizey wrote a half page review of it in The Telegraph, Bill Packer, a half page in the Financial Times and it was in the list of the 10 best things to do this Christmas in London in the Daily Express. Rod Stewart came to the private view. Oxtoby went on to exhibit with the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street in the 70s where the private views would sell out. Elton John bought Oxtoby’s canvases in vast numbers, for prices that were somewhere between Hockney and Picasso. He is still with the Redfern.

In 1974 I worked for Alex Postan Fine Art and was entrusted with getting publicity for the show of etchings, which included watercolours and acrylics as well as prints. It was the easiest job I have ever had. Marina Vaizey wrote a half page review of it in The Telegraph, Bill Packer, a half page in the Financial Times and it was in the list of the 10 best things to do this Christmas in London in the Daily Express. Rod Stewart came to the private view. Oxtoby went on to exhibit with the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street in the 70s where the private views would sell out. Elton John bought Oxtoby’s canvases in vast numbers, for prices that were somewhere between Hockney and Picasso. He is still with the Redfern.

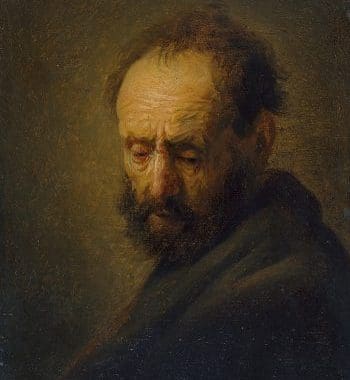

The pick of the bunch were definitely at Christie’s where the evening sale made £45M as opposed to Sotheby’s comparatively paltry £17.2M. In fact, the tiny pen and ink study of the Head of a Bear by Leonardo da Vinci, which sold at Christies for £8.857M made half the whole of the Sotheby’s evening sale on it’s own. My stand-out lots at Christie’s were first the exquisite Music Lesson by Frans van Mieris, on panel made out from a small arched-top painting to a larger rectangle by the artist himself, which, at £3.5M indicated that no-one was put off by the alteration to its shape. Second was the magnificent large View of Verona by Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, which took £10.575M. My third choice was the very rare canvas of Saint Andrew by the French follower of Caravaggio, Georges de la Tour.

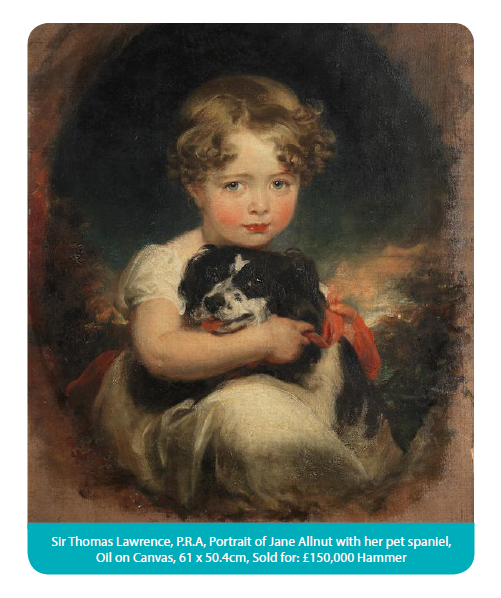

The pick of the bunch were definitely at Christie’s where the evening sale made £45M as opposed to Sotheby’s comparatively paltry £17.2M. In fact, the tiny pen and ink study of the Head of a Bear by Leonardo da Vinci, which sold at Christies for £8.857M made half the whole of the Sotheby’s evening sale on it’s own. My stand-out lots at Christie’s were first the exquisite Music Lesson by Frans van Mieris, on panel made out from a small arched-top painting to a larger rectangle by the artist himself, which, at £3.5M indicated that no-one was put off by the alteration to its shape. Second was the magnificent large View of Verona by Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, which took £10.575M. My third choice was the very rare canvas of Saint Andrew by the French follower of Caravaggio, Georges de la Tour.  This made a very respectable £4M. I don’t know how many paintings by this rare master are still in private hands, but it will be a tiny number. The only disappointment to my mind was the beautiful Lawrence portrait of Richard Meade, which sold for £598K, within the estimate but not a true reflection of its worth.

This made a very respectable £4M. I don’t know how many paintings by this rare master are still in private hands, but it will be a tiny number. The only disappointment to my mind was the beautiful Lawrence portrait of Richard Meade, which sold for £598K, within the estimate but not a true reflection of its worth.