Two tiaras, remarkably similar in design and created by Cartier for two society sisters are on display and sale in London this week.

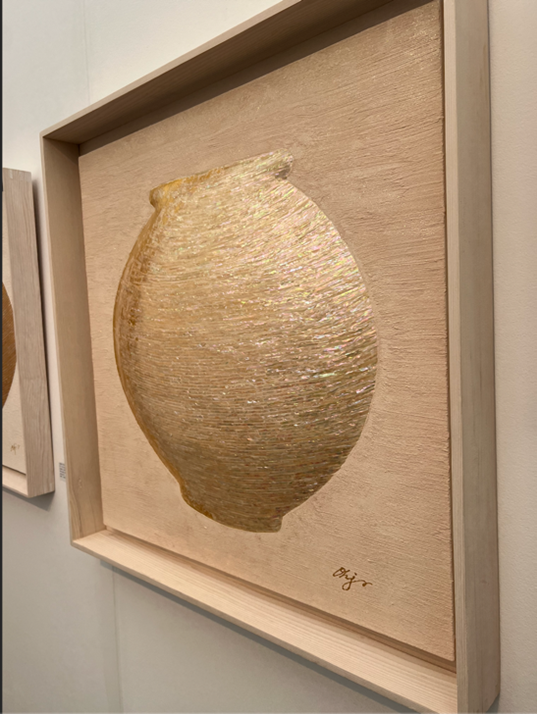

A hotly anticipated lot in Bonhams’ 5th June London Jewels Sale is the Astor turquoise and diamond tiara, owned by Nancy, Viscountess Astor. Estimated at £250,000-300,000, this incredibly rare piece dating from 1930 is seen on the market for the first time since it was sold to Lord Astor by Cartier London. The Astor Tiara comprises an earlier bandeau, circa 1915, that was adapted by Cartier using these beautiful turquoise carvings. The order for these carvings’ dates to 1929 and the finished piece was purchased soon after completion in 1930.

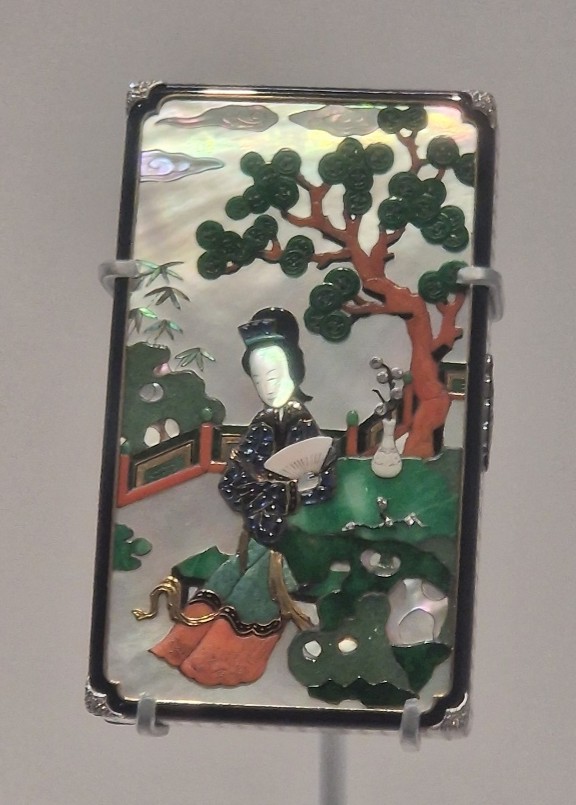

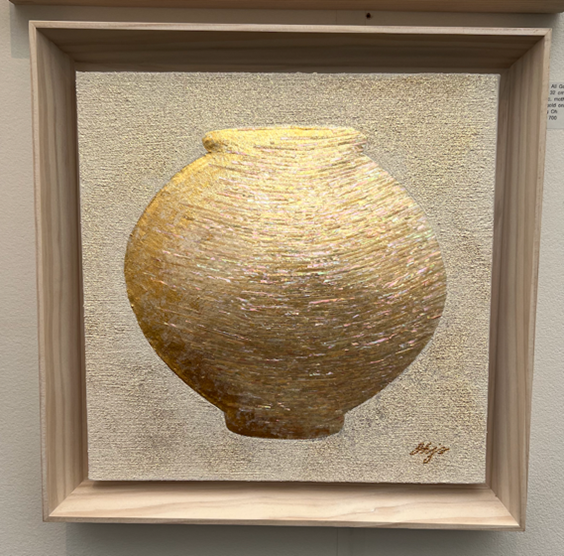

Incredibly, and reunited once more in London, is a second tiara, commissioned six years later for Nancy’s sister, Phyllis. Part of Cartier’s permanent collection, this remarkable reiteration and commissioned piece is on display as part of the Cartier exhibition at the V&A until November.

In the early 1930s, Lady Nancy Astor loaned the tiara to her sister, Phyllis Langhorne Brand for a court presentation at Buckingham Palace. Inspired by this exquisite Cartier jewel, Nancy’s brother-in-law, the Hon. Robert Henry Brand (1878-1963), commissioned Cartier to produce a similar turquoise and diamond tiara in 1935.

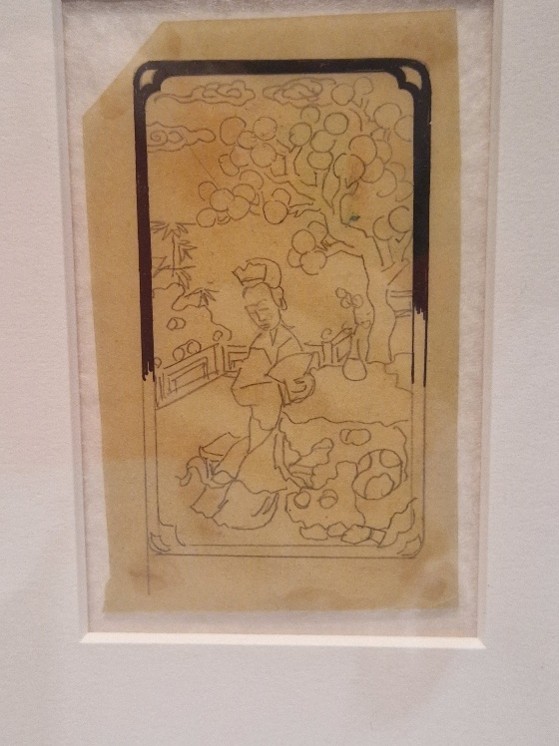

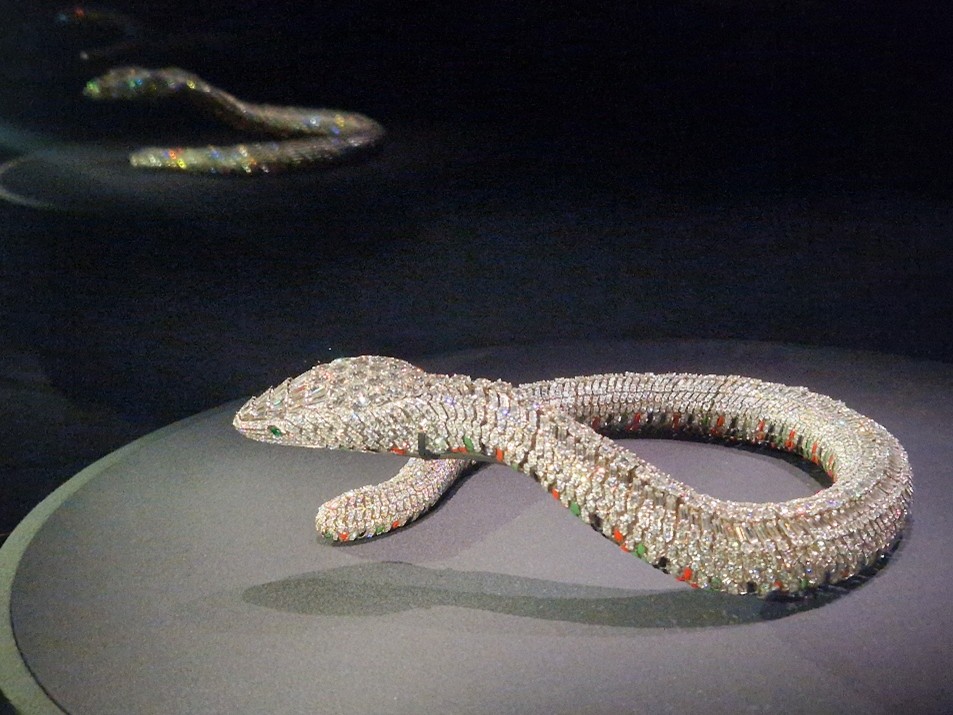

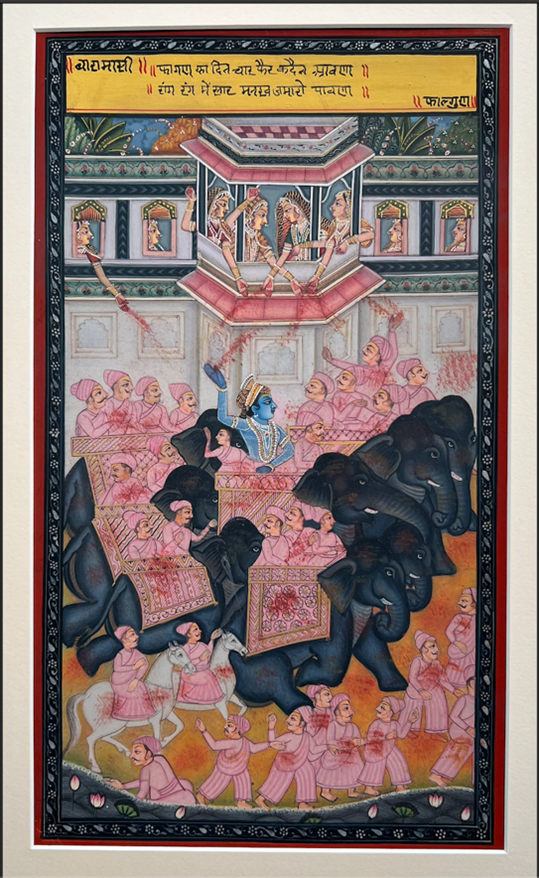

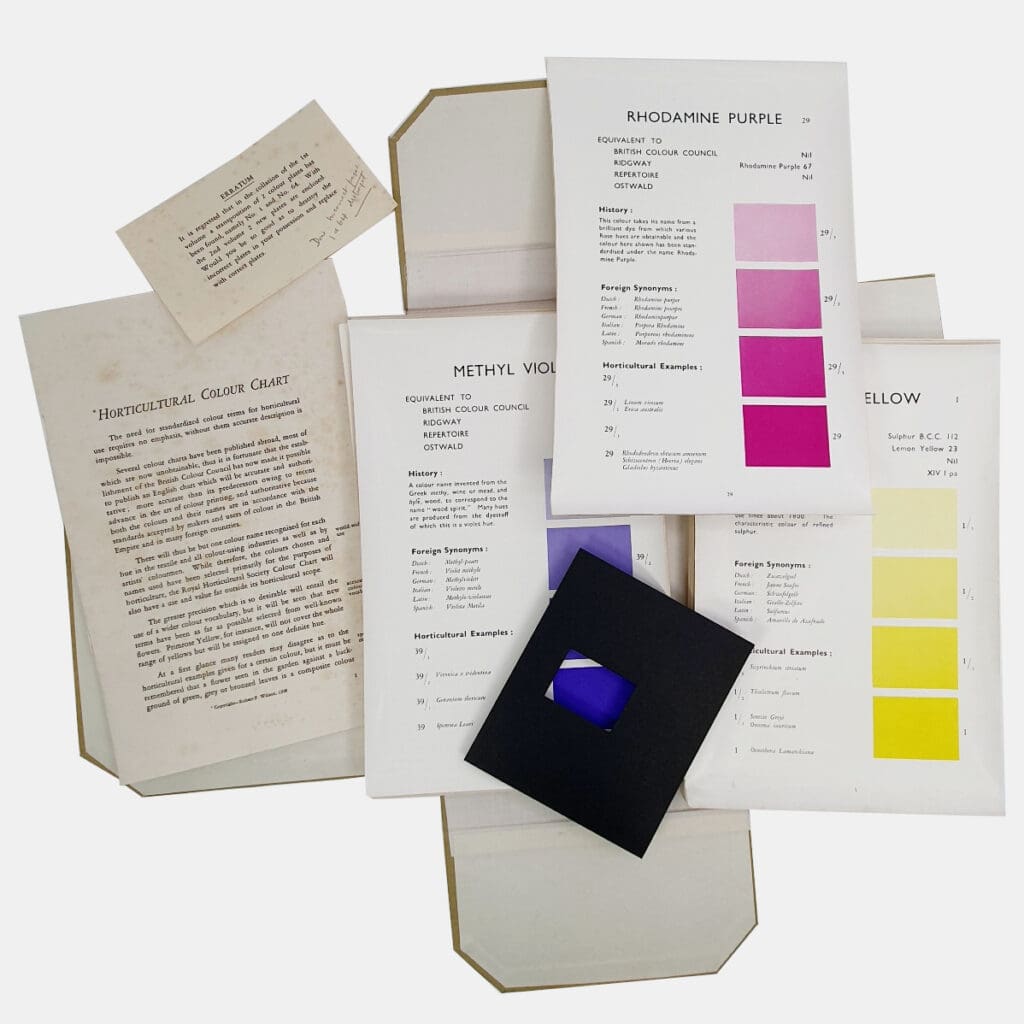

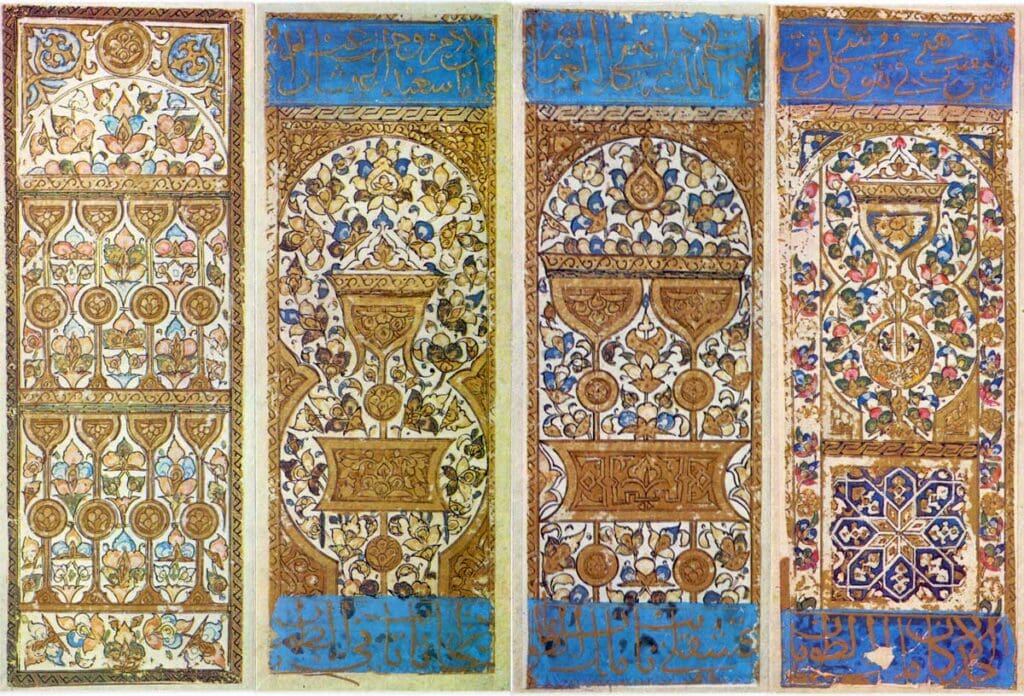

There are differences between the Astor and Brand tiaras, commissioned within six years of one another, yet both display the international influences in Cartier’s jewels of the time. The Astor tiara is detailed with carved turquoise plumes, leaves and scrolls that were drawn from Egyptian, Indian and Persian motifs. Similarly, the Brand Tiara features a teardrop shaped Boteh motif that originates to Iran, where turquoise was originally mined. The scrolling terminals on each were likely influenced by traditional headdresses worn in Thailand and Cambodia (V&A, 2025).

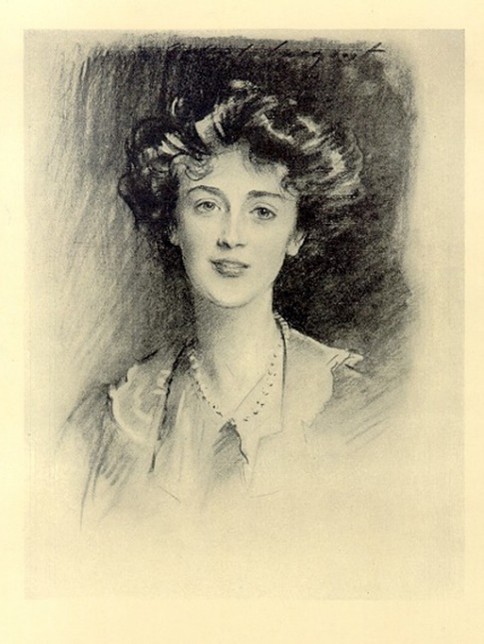

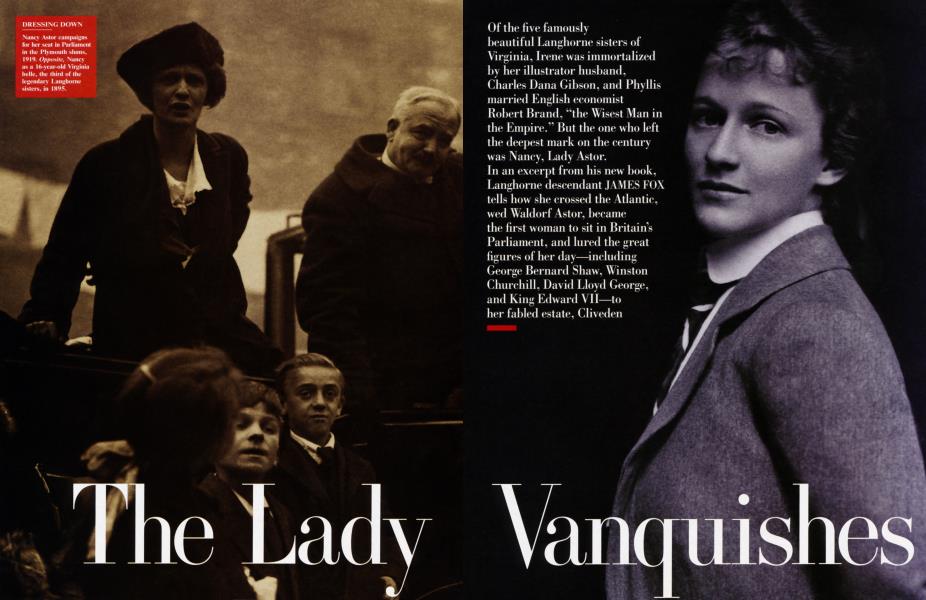

Sisters coveting one another’s clothing, jewellery – and tiaras – is a tale as old as time. Nancy and Phyllis were two of the five famously beautiful Langhorne sisters, born in Danville, Virginia, and four of whom found exciting and covetable lives in British Society. Nancy Astor met and married the 2nd Viscount Astor in 1906 and moved into Cliveden, Buckinghamshire. She quickly became a prominent part of the British social elite, and through her advocating for temperance, welfare, education reform and women’s rights in parliament she became the first woman to take her seat in Parliament, serving from 1919 to 1945.

Phyllis moved to London in 1913 and married English economist Robert Brand, “the Wisest Man in the Empire” in 1917. The two sisters were incredibly close – I would recommend further reading of their letters in Vanity Fair’s The Lady Vanquishes feature, written by James Fox in 2020.

These two tiaras not only display Cartier’s height of creativity and society commissions of the early 20th century, reflecting an international flair for design and a commitment to excellence. They also represent the tale of the two Langhorne sisters, their bond and shared – impeccable – taste.

Update: As expected, the Astor Tiara attracted a huge amount of interest from across the globe and was fiercely contested at Bonhams 5th June London Jewels Auction. Exceeding its pre-sale estimate three times over, this exceptional piece sold for a hammer of £700,000, totalling £889,400 inclusive of fees.

The Brand Tiara will be on display at the V&A Cartier Exhibition until November 2025.