- OpenSea.io

- Rarible

- Foundation

Boucheron, a brief history

The luxurious brand’s story starts when Frédéric Boucheron became an apprentice jeweller to Jules Chaise at the young age of 14 in 1844. Descendant from a family of drapers, he seemed to already have a thorough understanding of how to work with delicate fabrics like silk and lace.

He opened his first boutique in 1858 at Palais Royal, in Paris, next to the Louvre. A decade later, he won gold medal at the Exposition Universelle. He partnered with Paul Legrand for several years as chief designer. During their collaboration, Boucheron won the Grand Prix for Outstanding Innovation in a jewellery collection in 1889.

After winning this prize, Frédéric Boucheron opened the first boutique in 1893, Place Vendome in the heart of Paris. He was the first jeweller to take up space in this exquisite location, at n.26 where it is said that it was the sunniest part of the square and “the diamonds would sparkle all the more brilliantly”.

In 1900 he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur for his display at the Exposition Universelle, encapsulating the Art Nouveau style. He died two years later and left the Maison to his son Louis.

Outstanding and Unique Innovation

In 1879, Boucheron created a clasp-less necklace, named the “Point d’Interrogation” (the question mark). It was the first time a jeweller had created a piece of jewellery which women could place on themselves without any assistance if they so wished. Throughout the 164 years the Maison Boucheron has reinvented the style and adapted it to different styles with more or less foliate detail or a more contemporary look. It is its “stylistic approach, featuring asymmetry and curved lines” which make this necklace a signature piece for the jeweller, synonym of freedom and outstanding innovation.

Carat, 159 carat to be exact

Boucheron is synonymous of luxurious jewellery and “drapes” Royalty such as Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Rania of Jordan and some of the most famous women. One of these famous women of the 19th century was Marie-Louise MacKay, married to John MacKay who made his fortune through silver mining in the USA. She was intent on building one of the most important jewellery collections and Boucheron was her go-to jeweller. In 1878, Boucheron was entrusted with setting what was said to be the most beautiful Kashmir sapphire in the world, weighing 159 carats, of oval shape. It was valued at over Francs 700,000.

Hotel de Nocé

The Boucheron store is located in the grand Hotel de Nocé, built in 1717 and named after Charles de Nocé. The building has passed to numerous owners, including Jean-Baptiste-Francois Gigot d’Orcy, who had a passion for minerology. Sometimes the Hotel is called Hotel d’Orcy. The Hotel was home to some of the most famous people such as Marquis de la Baume, the “most expensive boot maker in the world” Yantorny and Countess Castiglione, also known as Virginia Oldoini, ex-mistress to Napoleon III. When Boucheron moved in to the building in 1893, “the most beautiful woman of her century” refused to move out until 1894. Two portraits of the Countess still look down on the boutique to this day.

Boucheron was the first jeweller to take up space on Place Vendome.

When Boucheron was bought in 2016 by the Kering group, they undertook a full restoration of the Hotel.

The façade of the building is listed which means that if Boucheron were to move out, it would be impossible for the new owners to make any changes. The inside was restored to its glorious state, with attention to detail such as Chinese wallpaper restored by Atelier Mériguet-Carrière.

With the renovation came the creation of hotel rooms, where guests come to spend a night within the Boucheron boutique at the heart of Paris.

Princess Eugenie

In 2018, on her wedding day, Princess Eugénie wore the Greville emerald and diamond tiara, initially created by Boucheron in 1900 and set with a 93.70 carat cabochon emerald, mounted in platinum.

The tiara in 1921 after modifications to include the centre emerald and a more geometric style, contemporary of Art Déco jewellery.

The Hon. Mrs Greville, who lived at Polesden Lacey, was a friend of Prince Albert and Elizabeth, Queen Mother. After they were married, the couple spent their honeymoon in Mrs Greville’s home.

In her will, Mrs Greville bequeathed the tiara to the Queen, who in turn lent it to Princess Eugénie for her wedding. It was the first time in over a century, that the Boucheron tiara had been seen in public.

Reflet wristwatch

In 1947, Boucheron created the Reflet wristwatch with interchangeable bracelets. The collection has a rectangular dial with baton hourmarkers and Roman numerals.

The watch comes in stainless steel or gold, with or without diamonds.

Not only was Boucheron the first jewellery to introduce this system, it has also added extra sparkle. Its sapphire glass is particularly magic: a breadth on the glass and the Place Vendome column appears for a brief instant.

Each watch is engraved to the reverse “Je ne sonne que les heures heureuses” (I only ring the happiest hours).

Only women

Traditionally, the jewellery industry has been male-led, but in 2015, Boucheron appointed Hélène Poulit-Duquesne as CEO and Claire Choisne, as Creative Director.

Hélène Poulit-Duquesne graduated from l’ESSEC, one of the most prestigious business school. She began her career in 1998 when she joined LVMH. Later she would join Cartier, where in 2014 she became Director of International Business and Client Development.

Claire Choisne also began her career in 1998. In 2001 she joined Lorenz Baumer as Creative Studio Manager. Over a decade ago, she moved to Boucheron, where she oversees all the jewellery and watches designs.

Boucheron has paved the way, once more, by handing the direction of a leading jeweller to two women, and has created resplendent new collections.

Nagaur necklace

In 2015, Claire Choisne integrated sand from the Thar desert in Rajasthan to include in the new Boucheron collection, the Nagaur necklace.

It is inspired by the Nagaur fortress.

The necklace is set with multiple strings of pearls with the sand encased in the rock crystal pendant, overlaid with diamonds.

The necklace is part of the Bleu de Jodhpur collection which comprises of 105 designs. Claire Choisne, says, “The aim was to create an image of India far from all clichés and stereotypes with the innovation of unused materials. The city of Jodhpur covered with the blue façades of its houses became a strong inspiration. Bold blue represents audacity because of the innovations behind the creations. The link between Jodhpur, the ‘Sun City’, and Boucheron, a jeweller in the ‘City of Light’, made the inspiration more obvious. India has always been an important concept in Boucheron’s creative history with its rich and vibrant heritage, the architecture of its palaces and the colours of its towns and cities. I believe that through audacity and maintaining a clear link between heritage and modernity, one is able to create figurative designs and thus translate this into contemporary high jewellery.”

A revival of the Plume de Paon is now set with marble and diamonds on white gold.

Boucheron is synonymous of luxury and exquisite craftsmanship. Throughout the centuries, the Maison has invented, innovated and reinvented its timeless pieces, moving through the fashions and adapting to contemporary designs. It undoubtedly has the “je ne sais quoi” that great and unrivalled French jewellers have.

This week marks the long awaited (for me at least) release of The House of Gucci on streaming services around the world. The Cinema release was of course one of those impacted by the pandemic, but thankfully not to the same degree as No Time to Die but realistically, nothing could be that delayed.

The film tells the story of Patrizia Reggiani and her downfall as the long-suffering wife of Maurizio Gucci, part of the much fabled and respected fashion house. Whilst the film takes some interesting turns and slight elaborations on history, what cannot be debated is the importance the house has in the world of fashion – be that in couture, handbags and even jewellery.

There are some things the Italians just do better; fashion, wine, and arguably cars (if you have read my article on Alfa Romeo, then you will understand my thoughts on this subject) and some of the classic designs in the handbag world have evolved from the house.

My personal favourite must be the 1947 Bamboo model, with perfect proportions and the daintiest outline. In a tan calf leather, it can be matched with anything, be it dressed up or down – as comfortable at dinner, as it is at the polo.

The great thing about Gucci, is that it sits at an affordable level, it doesn’t try to be Hermes, nor would it want to, the pieces are unique and instantly identifiable whilst maintaining a mid-level price, and for years have been very affordable, this however has changed in the last three years when the inevitable price increases have hit every fashion house, with Gucci being amongst Chanel, Hermes and Louis Vuitton seeing an almost 25% uplift

in replacement values.

The jewellery that Gucci produces is always bombastic and designed to create (and usually divide) opinions, its sits in a position that knows its place – whilst not high end it is good quality and more about design than its components, and over the years they have produced some stunning pieces, again my favourite pieces are a pair of 1970s silver cufflinks that are simply the definition of Milan in the era, not subtle but with enough flair to

get away with it.

With a lot of ‘fashion jewellery’ it sometimes is relegated to the bottom of the jewellery box along with Chanel and Dior pieces, however again with the price increases we are constantly seeing, perhaps it needs to be looked at in more depth – with the respect it deserves.

Nothing says I Love You more on Valentine’s Day than a big red heart – so if you’re the romantic type with deep pockets and a love of Urban art, why don’t you pop down to Sotheby’s on 2nd March and buy a belated Valentine’s gift for your better half?

Robbie Williams, the former Take That singer and one of the UK’s most successful pop star of the past 30 years, has decided to sell three major works by Banksy from his personal collection at Sotheby’s London contemporary sale. No doubt hoping to capitalise on the strong prices original works by Banksy have achieved in the last couple of years, Williams is offering a strong selection of iconic works for sale.

‘These works unite the cultural legacies of two of Britain’s biggest stars: Robbie Williams and Banksy,’ said Hugo Cobb of Sotheby’s. ‘Like their creator and like their owner, they are acerbic, iconic, irreverent and unique.’

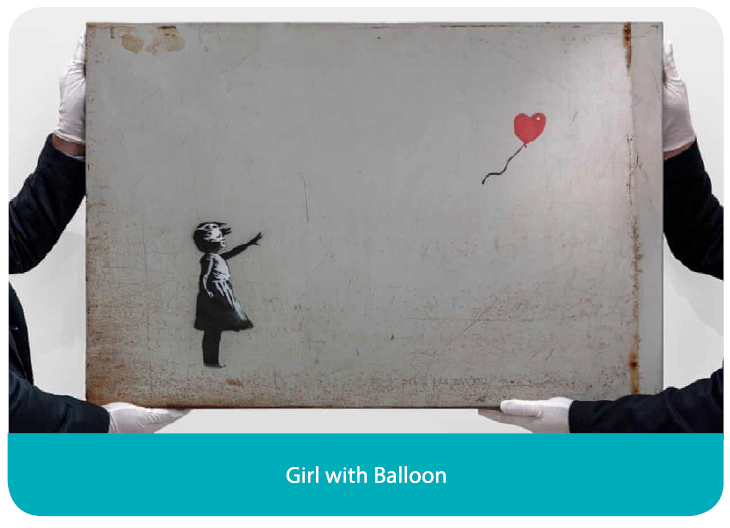

The earliest work of the group is a 2002 unique version of Banksy’s famous Girl with Balloon, painted on a metal sheeting. This work is earlier than the infamous 2006 version which was shredded live during a Sotheby’s auction in 2018, and which subsequently sold again last year at Sotheby’s under the new titled of Love is in the Bin, making £18,500,000 – a world record for the artist. The Williams version might not have the notoriety of the shredded work, but its strong rock ‘n roll provenance, and the fact that it is the only version painted on metal to come to auction, will no doubt ensure a strong result. The work is estimated at £2m-3m.

Also up for sale is a 2005 version of Kissing Coppers, which depicts two male British police officers in a passionate embrace.

This image first appeared on the outside wall of the Prince Albert pub in Brighton in 2004 and was a very public demonstration for Banksy’s support for acceptance of homosexuality. The original mural was removed in 2014 after being repeatedly vandalised, but you can buy the Williams version at Sotheby’s, which is estimated at £2.5m-3.5m.

The third and final work being offered is a strong example of Banksy’s Vandalised Oil series, in which Banksy has superimposed a stencil of two military helicopters flying over and disrupting a serene pastoral landscape. It is part of a series of works the artist made in which he superimposes graffiti and stencilled images on top of traditional paintings. Flying Chopper, carries a pre-sale estimate of £2.5m-3.5m, but it will no doubt attract strong interest from buyers.

The three works were available for viewing at Sotheby’s New York between January 22nd-27th, Hong Kong between February 8th-9th, and are now heading back to London for the final public viewing from February 22nd before being sold on 2nd March.

Of course, if your Valentine’s Day budget is a little too modest to allow you to buy the famous big red heart for your loved one, I’m sure a box of chocolates will do just fine!

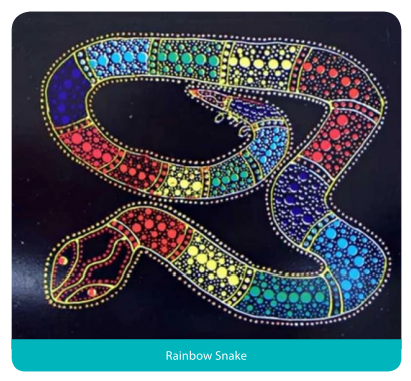

According to Aboriginal legend a giant rainbow snake formed the main rivers throughout Australia when he slithered across the land in search of water. The water in Australia is said to be blessed by the Rainbow Serpent, as water is one of the necessities of life. Without the Great Artisian Basin, a body of water under the Australian Earth, opal would not have been formed. There are therefore great connections between the Rainbow Serpent and the opals of Australia.

Opals are truly mesmerizing treasures of the earth, the way their vibrant colours dance with the light. Australia has been the main producer of opals since the 19th century. Opal is a hardened silica gel composed of tiny silica spheres and the stunning iridescence seen in opal is caused by the way these little spheres interact and diffract light. The larger the spheres the greater the range of colours.

Many people believe opals to be unlucky because it is quite common for opal stones to fall out of their setting and be lost. However, this is not because of some great curse, it is due to the fact that opals are composed of 5-10% water and over time they can dry out and shrink and therefore become loose and fall out of jewellery settings.

The major mines in Australia can be found in Queensland, New South Wales, and South Australia. When valuing and grading an opal it needs to be assessed under the correct light source. It needs to be examined holistically – face up but also underneath, if the setting allows, so that any defects, holes, and fractures can be taken into consideration. The following factors determine the value: the opal type – i.e. solid black, grey, white, crystal type, The origin, body tone, play of colour, colour depth percentage, colour pattern, shape, cut, polish, weight, dimensions, visual inclusions, condition, and provenance.

One of the most famous Australian opals is The Aurora Australis. It was discovered in 1938 in Lighting Ridge (NSW) in an old seabed. Its body colour is black which highlights the dramatic play of colour of intense blues, greens, and reds. It got its name because it resembled the brightness of the Southern Lights. It weighs 180cts and has been cut and polished into an oval shape. It is said to be worth an estimated $1,000,000 AUD.

Opal can also be found in other countries such as Ethiopia, USA and Mexico, however Australian opal is considered the finest. As with most gemstones there are many synthetic opals and opals that have been artificially enhanced on the market. Slocum stone is a man-made glass that imitates the play of colour in opal. Gilson imitation opal has a very defined mosaic pattern which can be detected under magnification that is said to resemble chicken wire.

Black opal is the most highly prized and valuable, however before purchasing the consumer should be aware of treatments such as ‘smoking’. The opal is wrapped in paper and the paper is heated to a temperature that makes it smoulder. The smouldering paper then releases fine black particles of soot that enter the pores of the opal and darken its body colour.

The darker body colour contrasts with the opal’s play-of-colour, making it appear stronger and more obvious. Many Ethiopian opals are smoked and consequently are less valuable. The question is can you tell the difference?

“In precious opals there might be a dash of red here, a seductive swirl of blue there, and in the center, perhaps, a flirtatious glance of green. But each stone flickers with a unique fire and a good opal is one with an opinion of its own.” Victoria Finlay

History is crawling with jewellery depicting bugs and minibeasts. Our preoccupation with insects and mini-reptiles is thousands of years old. Mankind has always made jewellery to be beautiful, but also often talismanic. In the case of bugs and minibeasts it was believed the jewellery would bring to the wearer the attributes associated with creatures themselves.

Ancient Egyptian scarab images are familiar to most of us. The Egyptians saw the beetle as a symbol of renewal and rebirth. It was believed to be a manifestation of Ra, God of the sun, and the connection was thought to be so powerful that the sun god was considered to be reborn each morning in the form of a winged scarab beetle. This connection with renewal, rebirth, hope and good luck makes it easy to understand why the scarab has such a prominent place in jewellery from ancient times and remains a potent and popular motif to this day.

The interest in all things Egyptian reached a crescendo with the Egyptian Revival, a movement centred around archaeological discoveries in the 19th century, the translation of the Rosetta stone; the construction of the Suez Canal and later, importantly, the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun; in which there was, of course, much jewellery, including gold and carved lapis lazuli scarab jewellery which was put into the tomb to help with the transition to the next life.

These events provoked a huge wave of popularity in all things Egyptian; including an interest in snakes which became hugely commercial in the Victorian period. This trend was undoubtedly encouraged by the engagement ring presented to Queen Victoria by Prince Albert in the earlier part of the century. The ring, in the form of a coiled snake, symbolised eternal love with its endless coil. Victoria’s ring was set with an emerald to the head, this being Victora’s birthstone. Known as an ouroboros, the emblematic snake or serpent with its tail in its mouth represents eternity and rebirth. It is a motif which occurs frequently in jewellery, not only in rings but also necklaces and often suspending a heart locket.

The bee was also an important symbol in some early civilisations. It was considered to be sacred and was believed to be a bridge between the natural world and the underworld. The Mayans thought that the bee was a symbol of goodness and would bring life and abundance. Ancient Greeks saw bees as characterising wealth and well-being. The hierarchy of the hive with its Queen and workers as well associations with hard work and individuals working together for communal good added to the imagery. It is easy to see why humankind has been drawn to the bee as a powerful symbol.

The fascination with insects and minibeasts arguably reached its zenith in 19th century. The rise of industrialisation and with it rapid urbanisation meant a large migration to town and city dwelling. This gave rise to a nostalgia for the countryside and nature. People felt that they were falling out of step with nature, and they sought to reconnect through jewellery depicting birds and insects.

It’s easy to see why butterflies, lady birds, and dragon flies lend themselves to beautiful and inspirational jewellery. However, the Victorians embraced all insects, including flies which symbolised secrets and secret keeping; as well as the fly on the wall which hears all but does not divulge. Spiders, similarly, were related to intrigue and secrets and remain a perennially popular motif. You may remember Baroness Hale wore a substantial spider brooch when delivering the verdict on the legitimacy of Boris Johnson’s prorogation of parliament. There was much speculation about what she might have intended to convey. Retrospectively, she said that had she known that people would be looking to interpret the brooch she might have chosen innocuous bunch of flowers. However, the episode serves to show the power of the symbolism. Politicians started to wear spider brooch tee-shirts and the late Ruth Bader-Ginsburg described the stylish arachnid as ‘a symbol of swashbuckling womanhood’. Not bad for a costume piece that had cost £12 from Cards Galore.

We are drawn to wear insect jewellery for its symbolism and meaning, but that is not the whole story. The other side of the equation is how well the subject matter lends itself to interpretation in so many of the media associated with jewellery making; from fine pavé set pieces with emeralds, diamonds, rubies and sapphires, to enamel work, glass, carved stones and pearls. The interpretations are almost limitless, as is the appetite for this jewellery. Although not every interpretation is easy to stomach. Now considered in questionable taste we have also used the body parts of insects themselves as part of the jewels, including butterfly wings and scarab shells. Even this, however, is not as distasteful as the practice of late 19th century Britain, and still current in some parts of South America, of wearing live insects, sometimes caged and occasionally even with jewel encrusted shells.

Notwithstanding the huge influence of the 19th century, insect jewellery continued to be popular in the early 20th century. René Lalique produced some exquisite plique-a-jour butterfly and dragonfly pieces. Child and Child produced realistically designed butterfly pieces in shaded enamels; Boucheron is known for its bee pins and many other important ateliers produced fine gem-set pieces in this genre. These are always in high demand when they come up at auction.

Hello magazine recently announced, ‘Butterfly jewellery is making a comeback’. Good to know, but it’s never really gone away. The Duchess of Sussex often wears a pair of butterfly earrings which used to belong to Princess Diana and other celebrities are pictured with butterfly jewellery; but the truth is that this jewellery has never gone out of fashion. Prices at auction are strong with huge demand for good pieces; but more modest offerings do well too. Whether antique or modern where demand is great, price matches demand. As I have been writing this two of the pieces illustrated, the snake necklace and the costume butterfly brooch went under the hammer. Both realised twice their higher end estimates. Proof, if proof were needed that the world of insects is indeed buzzing – sorry, I couldn’t help myself!

2022 is not a year that anyone except the most reclusive could possibly claim not to have heard of the Australian Tennis Open – the high profile legal wranglings between the Australian Government and Novak Djokovic over his entry visa, covid vaccinations and his deportation, have made the already famous sports tournament front page news worldwide. Founded in 1905, the Australian Open, or the ‘happy slam’ as it is affectionately known, is the first of the 4 grand slam tournaments worldwide, which takes place in Melbourne every year. Although it is not the highest paid tournament (the prize money is only A$75m!), the Australian Open is by far the most popular in terms of attendance numbers, with 812,000 spectators attending the 2020 tournament.

Notwithstanding our current fascination with the dramas playing out in Oz, we, the public, have always had a fondness and affection for the game of tennis, one which is totally different to that of other sports, and one which goes back centuries to its origins. The racket sport we now call tennis, is the direct descendant of ‘real’ tennis or ‘royal‘ tennis, which continues to be played today as a separate sport with more complex rules. Most historians believe that tennis originated in the monastic cloisters in northern France in the 12th century, but the ball was then struck with the palm of the hand; hence, the name jeu de paume (game of the palm). It was not until the 16th century when rackets came into use, and the game as we know it emerged. The roots of the game are firmly linked to the royal courts of France and England, with Henry VIII of England being one of the most avid players of his day – his luxurious tennis courts still remain to this day at Hampton Court Palace. In France the sport was so firmly associated with the Court and Nobility that during the Revolution many of the tennis courts we deliberately destroyed as a sign of a new era emerging.

Subliminally these Aristocratic links and associations have remained with us into modern times. Tennis still has the perception of being a genteel sport, one which is played out on immaculate lawns on sunny summer afternoons, with players dressed in immaculate tennis whites. One only has to look at Wimbledon to confirm this – the tournament is so much more than simply a sporting occasion, it has become a firm part of London’s social season, with its Royal Box, champagne, strawberries and cream! Without doubt this image belies the seriousness of the sport, and the huge financials at stake in modern tennis, however, it is also this je ne sais quoi that also adds to its modern success.

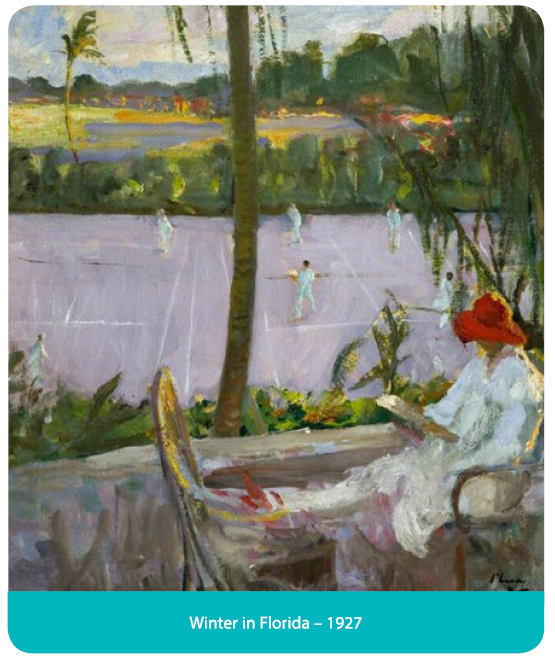

Depictions of tennis in western art very much follow the image of tennis as a jolly, social pastime played by the leisured classes and gilded youth. The summer is always eternal, and the player are carefree without a worry in the world! One of the most brilliant and prolific painters of this subject is the Victorian artist Sir John Lavery, who is more usually associated with the glamorous and elegant society portraits he produced throughout his life. Tennis, however, fascinated him and he returned to paint the theme on a number of occasions, producing both informal studies and highly complicated compositions.

One of the earliest depictions is Lavery’s 1885 painting, Played!! which captures the movement and drama of an exciting new sport, as a young woman lunges to return serve. In the early 1880s, Lavery had returned from Paris, where he was studying at the prestigious Academie Julian, and was quickly taken by the game. In the summer of 1885, he visited the home of a friend in the suburbs of Glasgow, where a tennis court had been set up. The painting was inspired by this visit, and marked a new direction for the artist, away from his more usual society portraits towards depictions of ‘modern’ life – no doubt influenced by the Impressionist works he would have seen during his stay in Paris. His choice of the subject and naturalistic portrayal was considered extremely avant-garde at the time. Lawn tennis was then at an interesting stage in its development as a modern sport. It had emerged in the 1870s and had been inaugurated at Wimbledon as recently as 1877, when the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club introduced men’s singles championships. Ladies’ singles and men’s doubles had not been incorporated until 1884. The process by which women arrived on court was a gradual one, then, and mixed doubles matches were yet to come.

Played!! turned out to be a mere prelude to Lavery’s undoubted masterpiece on the subject which painted the same year. The Tennis Party, which is in the collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, is an absolute tour de force of a painting, showing huge sophistication of composition, movement and bravura brushwork. In spite of its apparent spontaneity the picture is not merely an arbitrary slice of life, rather it is highly constructed work aimed at giving the illusion of spontaneity. The depiction of both male and female players in the same game, which seems uneventful to a modern viewer, would have been the height of modernism at the time, where casual, real-time depictions of the opposite sexes cavorting together was very rare at the time.

Throughout his career Lavery, returned often to the subject of tennis, which more than any other sport held his fascination. Although Lavery’s first depictions of tennis might have been painted in Scotland, his later works were increasingly international showing the growing popularity of the sport. The paintings Lavery produced in the first quarter of the 20th century whilst on the French Riviera and in America are some of the most spontaneous and evocative depictions ever produced on the subject. Whether they were painted at the famous courts at the Hôtel Beau Site in Cannes – then ‘the’ place to go for well healed British holiday makers, or at the courts of the Breakers Hotel in Florida or in the private residences of Palm Beach, these paintings have a freshness and sense of movement which still have the power mesmerise to this day.

Lavery’s 1885 The Tennis Party remains, however, his most accomplished and monumental depiction of the sport, an image which, more than any other artwork has influenced our vision of what we feel tennis ‘should’ be, and it remains to this day the quintessential image of the sport.

It’s fantastic to see so many new artists’ work coming to the fore all over the globe, and how the role of buying and selling fine art is evolving to attract new audiences.

Somehow the art world has managed to fast forward thanks to technological advances brought in as a matter of necessity during the pandemic, removing many or all of the old barriers that were putting first time buyers off auctions, or more positively pulling them in!

As an auctions career ‘lifer’ myself, I have always believed it’s a numbers game. The more active bidders you have in any auction the better it will perform.

Thanks to technology – Christie’s managed, in a heartbeat, to get from an average 8-1,200 hundred online bidders to 50,000, which is what happened at their global ‘one’ event in 2020. There were so many bidders that when I tried logging on, it bounced me out!

Although the online affect could diminish as the post-pandemic era progresses, thousands of new collectors and buyers are now hooked as auction houses have demystified the process of an auction.

I can see that it’s happened by accident and not design. We’re entering into a new era with contemporary art auctions still growing, Old Masters are doing well especially Prints. Jewellery, Watches and Design are still strong but the focus is heavily on masterworks or special pieces.

New ways of selling are now starting to emerge thanks to the new owner of Sotheby’s Patrick Drahi who bought the business pre-lockdown. He has quite logically seen his brand is much more able to penetrate into new areas. Yes Sotheby’s is an auction house but it’s also a luxury shop selling branded goods.

Christie’s ‘One’ live auction held all one day July 10th 2020, it was one very long auction broadcast from four locations starting in Hong Kong,

then switching seamlessly to Paris, London and finally New York

New auctioning ideas are appearing all the time with the most recent being the Las Vegas MGM Grand live auction of works by Picasso from the Casino Picasso Dining room this October. Only 11 pictures, all by Picasso were in the auction, and raised a staggering total of $110,000,000 from what is only a selection of works the Casino owns.

The next day luxury items, sneakers, handbags, watches and the like all did equally well in a smaller MGM Casino downtown. This was truly an event auction and I think it will set the trend for the years to come.

I think we can all be encouraged by the fact that more people than ever before are taking an active interest in auctions both as buyers and sellers.

Here are some fine art pieces sold highlighting what an extraordinary year 2021 has been.

“There are too many auctions and not enough collectors”, that is how Scott Reyburn’s article in the Art Newspaper in December 2021 began. It makes rather gloomy reading for any fan of Old Masters, but it is, sadly, the truth. Sotheby’s and Christie’s sales were down 20% on the year before the pandemic (2019). If a good Old Master in excellent state comes on to the market after an absence of several decades, it will make a strong price but there are simply not enough of them.

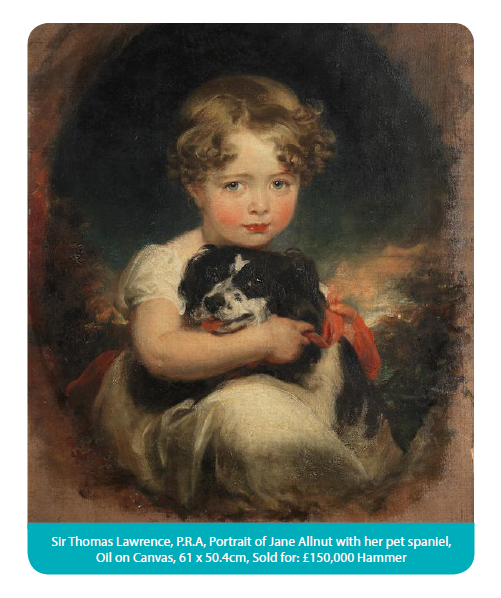

For those of you lucky enough to have come to our champagne private view at Bonhams, you might be interested to hear what happened to the paintings we examined there. The beautiful unlined, unrestored Lawrence of Jane Allnutt with her spaniel made £150,000 hammer, which I think is less than it deserved. The early Turner watercolour of North Wales, painted in rather muted tones made £40,000 which was twice the bottom estimate. The famous racehorse, Flying Childers, however, did not fly and is still under starter’s orders.

Rather than dwell on what were basically mediocre paintings making mediocre prices, I’d like to draw your attention to a couple of surprises. There was a very fine portrait of a man attributed to Frans Hals by Sotheby’s, which they offered with a very cagey estimate of £80,000-£120,000. The reason for their caution was that the two main experts on Frans Hals disagreed about its authenticity and the more recent of the scholars suggested it was by his son.

Not knowing what his son’s work looks like, I thought it looked like Frans himself. I was not alone in this as it made £1.95 million!

Sotheby’s also had, like Bonhams, an early Turner, theirs too was also Welsh, but this one was in oil and South Walian. It was a view of Cilgerran Castle dated 1799 and made £1 million against an estimate of £300,000-£500,000 proving once again the magic of the Turner name. The Constables on offer had a more varied outcome mostly due to the erratic estimating.

I am into my 6th decade of looking at Old Masters professionally and I am feeling the icy blast of change. The storm of interest in NFTs is going to have a detrimental effect on the way all collectors perceive art. The young are tech-savvy and non-materialistic, so is there a subtler way of collecting than virtually? Will the virtual supersede the real?

We all know at this time of year Santa is extremely busy, up against a very tight deadline. I’ve not come across Santa myself, but in my imagination, he surely must be wearing a pocket watch so he can keep on top of his schedule and targets in good time. And let’s not forget he has a lot to do in just 24 hours so time is of the essence.

In my mind, the pocket watch is mounted in yellow gold, with delicate floral chasing. Chasing is a technique where the jeweller outlines a design by pushing back the gold around the edges to define the motif. I would imagine the watch to be old, dating from the late 19th century, and so it would also be decorated with some guilloché enamel, perhaps blue or pink; Santa is dapper and I am sure he appreciates a touch of colour outside of his red and white suit. Guilloché is one of my favourite techniques of applying enamel. It creates all sorts of highly elaborate patterns which adds elegance to any piece of jewellery. Perhaps the watch has both pink and blue enamel: a pink guilloché enamel bezel overlaid with blue enamelled Arabic numerals. The hands would be discreet, also made of gold. It is most likely suspended by a fine pinchbeck chain, terminating in a barrel clasp decorated with turquoise cabochons.

Pinchbeck chains are named after an 18th century London clockmaker, who used a combination of copper and zinc to make it resemble gold. Gold only came in 18ct at the time and was expensive. This new technique allowed people to purchase gold-like jewellery.

The pocket watch might look something like this:

To the reverse, the pocket watch would enclose a photograph of his wife Mary.

Santa probably has family heirlooms too such as a signet ring set with a stone. That stone could be lapis lazuli (blue with specks of “gold” pyrite), onyx (black) or carnelian (red) for example. The ring could be set with a carnelian intaglio mounted in gold. Intaglio is the technique of carving into the stone to depict a portrait for example. Santa’s intaglio would be carved with a cherub to represent all the children of the world.

He most likely also has another signet ring set with a bloodstone: green jasper with specks of red hematite, the stone of courage. It is engraved with his initials “SC”, the motto “No child to far to reach” and a family crest depicting his reindeers and helpers. Santa can then seal all his letters, replying to the children who have written to him throughout the year.

Santa also wears cufflinks under his red suit. One might be able to get a glance at them when he is in his workshop perhaps, when he is not wearing his red jacket. The cufflinks are by Cartier, from the Santos line. They are square plaques set with malachite, a green stone, set in palladium. They are chic and timeless, Cartier’s signature.

I believe Santa also wears a necklace, a gold box chain.

It suspends the very important keys to his sleigh but also several small pendants which represent all the faiths of the world, throughout time.

Lastly, I think Santa wears a bracelet symbolising his reindeers. It is of chevron design, mounted in rubber and silver. Here an example of what it might look like by David Yurman.

It echoes ancient jewellery that used strands of braided human hair set as bracelets.

The same technique was used with elephant hair.

These are the jewels I imagine Santa to be wearing, but I’m sure whatever he wears he looks dashing! Here’s hoping I might finally get a glimpse of him this Christmas. Wishing you all Happy Holidays.