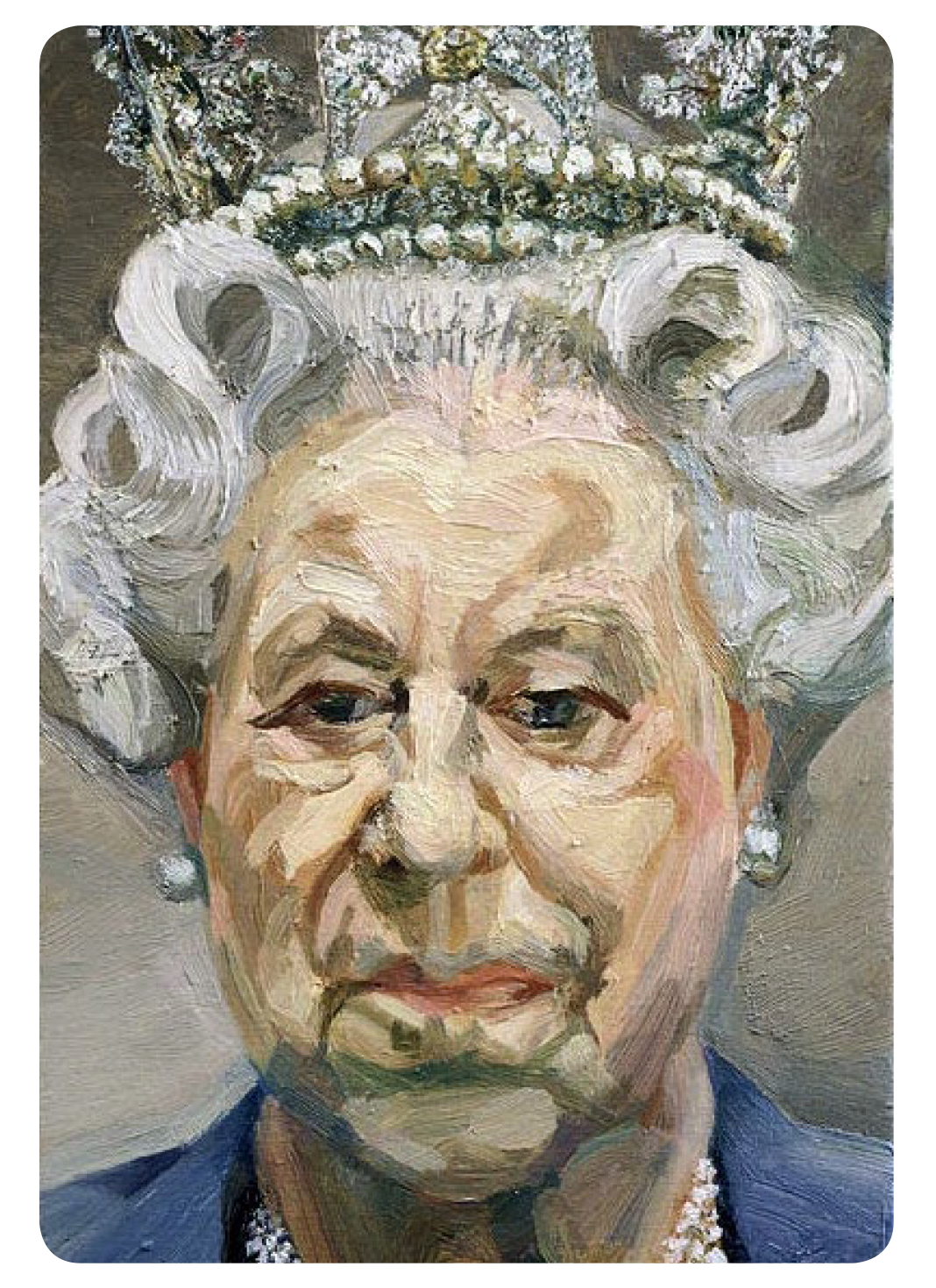

If one wants a glimpse of The Imperial State Crown, it is on display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London, as it has been for the last 600 years. But on the 19th September 2022, this most unique and priceless item of jewellery laid on her Majesty The Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin for her final farewell.

During her reign, Queen Elizabeth II would wear it annually for the State Opening of Parliament, sharing in 2018 that “You can’t look down to read the speech, you have to take the speech up, because if you did your neck would break”. The crown weighs 1.06kgs.

Monarchs wear the Imperial State Crown when departing from the Abbey after the coronation, and for all other occasions requiring crown-wearing thereafter.

Originally made by Rundell and Bridge in 1838 for the coronation of Queen Victoria. It was commissioned for the coronation of the Queen’s father, King George VI in 1937 from Garrard & Co.

The crown is set with historical gems with nearly 3,000 stones – including 2,868 diamonds, 273 pearls, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds, and five rubies.

The Culinan II, or Second Star of Africa, weighs 317.4 carats, with 66 facets.

Cullinan produced 9 major stones of 1,055.89 carats in total, including the Cullinan II, plus 96 smaller brilliant and some unpolished fragments weighing 19.5 carats. The Cullinan diamond was found in 1905 in South Africa’s Premier Mine at Cullinan, named after Sir Thomas Cullinan, who opened the mine in 1902. It is believed the diamond surfaced 1.18 billion years ago. Originally thought to be some priceless crystal, the mine’s manager did not give another look when the miner found it. He persevered, and it then became the largest diamond to be found.

It was sent to London in a plain box via registered post and presented to King Edward VII. It remained unsold until 1907.

The Transvaal Colony government bought the diamond on 17 October 1907 for £150,000, the equivalent of £18 million. It was presented to the King on his 66th birthday at Sandringham House.

He accepted the gift “for myself and my successors” and ensured that “this great and unique diamond be kept and preserved among the historic jewels which form the heirlooms of the Crown”

The king chose Joseph Asscher & Co. of Amsterdam to cleave and polish the rough stone into brilliant gems of various cuts and sizes.

Cutters here in Amsterdam plan how the stone should be cut. It took 8 ½ months to cleave and cut.

The images above show Joseph Asscher cleaving the Cullinan.

On the first blow, Asscher’s hammer blew off. It was on the second attempt that the diamond shattered into 9 pieces.

Cullinan I is set in the sceptre, which also laid on the Queen’s coffin.

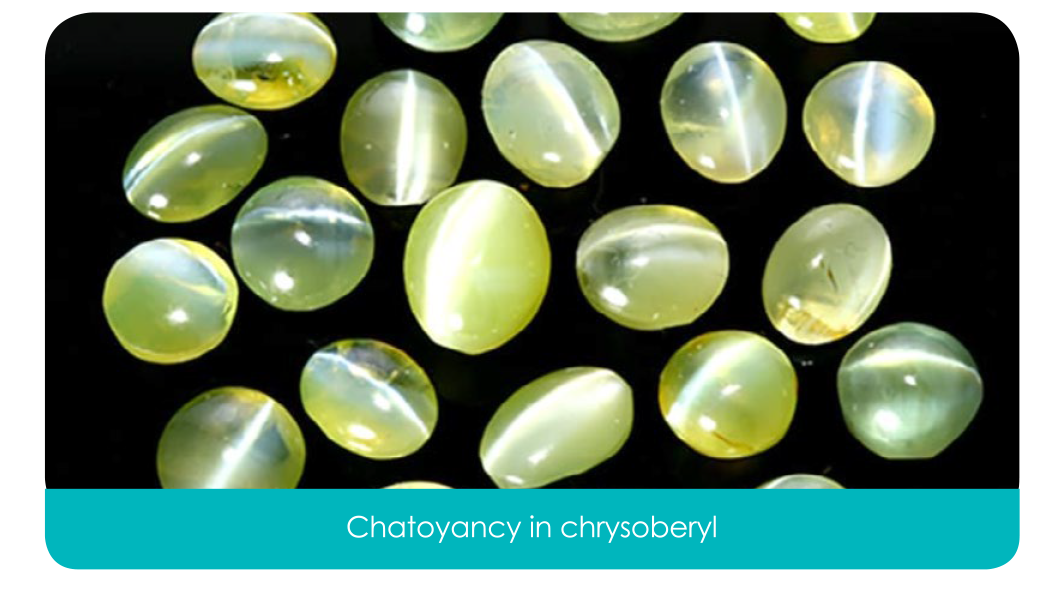

The Black Prince’s ruby, in its prominent place on the crown, is in fact a spinel. It was only in 1783 that spinels were differentiated from rubies. They share many chemical properties, such as aluminium, oxygen, and chromium but spinels also have magnesium.

This “ruby” is said to have been in English royal hands since the 1360s.

It was probably discovered in the Himalayan mountains of central Asia, in the Badakhshan (Balascia) region that was famed for its spinels. It drilled at some point to be worn as a pendant. The hole was later filled with a smaller cabochon ruby edged in gold.

It was supposedly worn by King Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 and saved him from an axe blow to the head, struck by the Duke of Alençon. Henry survived, as did the ruby, and the English were victorious.

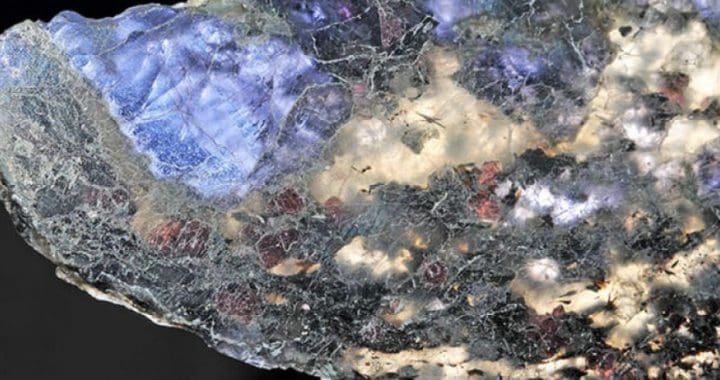

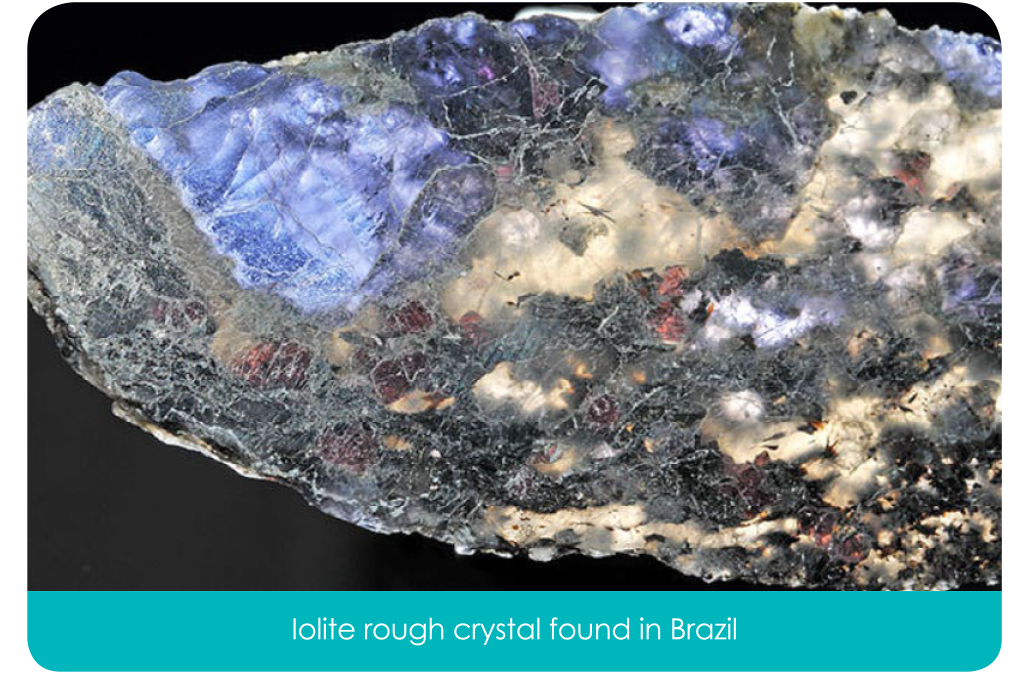

The Stuart Sapphire is set at the back of the crown and weighs approximately 104 carats.

In Youngblood and Davenport “The Crown Jewels of England”, they describe the stone as follows: “oval in shape, about one and a half inches in length, by one inch in breadth, and is set in a gold brooch. It has one or two blemishes, but is of good colour, and was evidently deemed of high value by the Stuarts. At one end has been drilled a hole, probably to introduce some attachment by which the stone could be worn as a pendant.”

Queen Victoria, was the first monarch to have the sapphire set in her state crown. During Victoria’s reign, the sapphire was set at the front of the crown, just below the Black Prince’s Ruby.

After the discovery of the Cullinan diamond, the sapphire was relocated to the back. There is still some mystery as to whether the Stuart sapphire in The Imperial State Crown has been the same gem since it was first used in royal jewels in 1660 but it certainly has been in the collection for over two centuries.

These priceless gems, the Cullinan II, the Black Prince’s Ruby and the Stuart Sapphire are a reminder of majesty, sovereignty and tradition embodied in the institution. Following tradition, King Charles III will wear the St Edward’s Crown for his coronation, but will put on the Imperial State Crown to leave Westminster Abbey at the end of the ceremony.

God Save the Queen, Long Live the King.