There are six types of precious coral from deepest red to porcelain white and none are endangered.

Did you know that Mediterranean Rubrum coral is still dived for by hand by around 50 licenced divers at a depth of 50 metres? Japanese and Taiwanese coral is even deeper; at a depth of 80 metres to 300 metres and can only be harvested by a submersible with strict quotas.

It is reef and shallow water coral, such as golden and black coral, that are endangered. These are known as common coral and reside on the global CITES protection list.

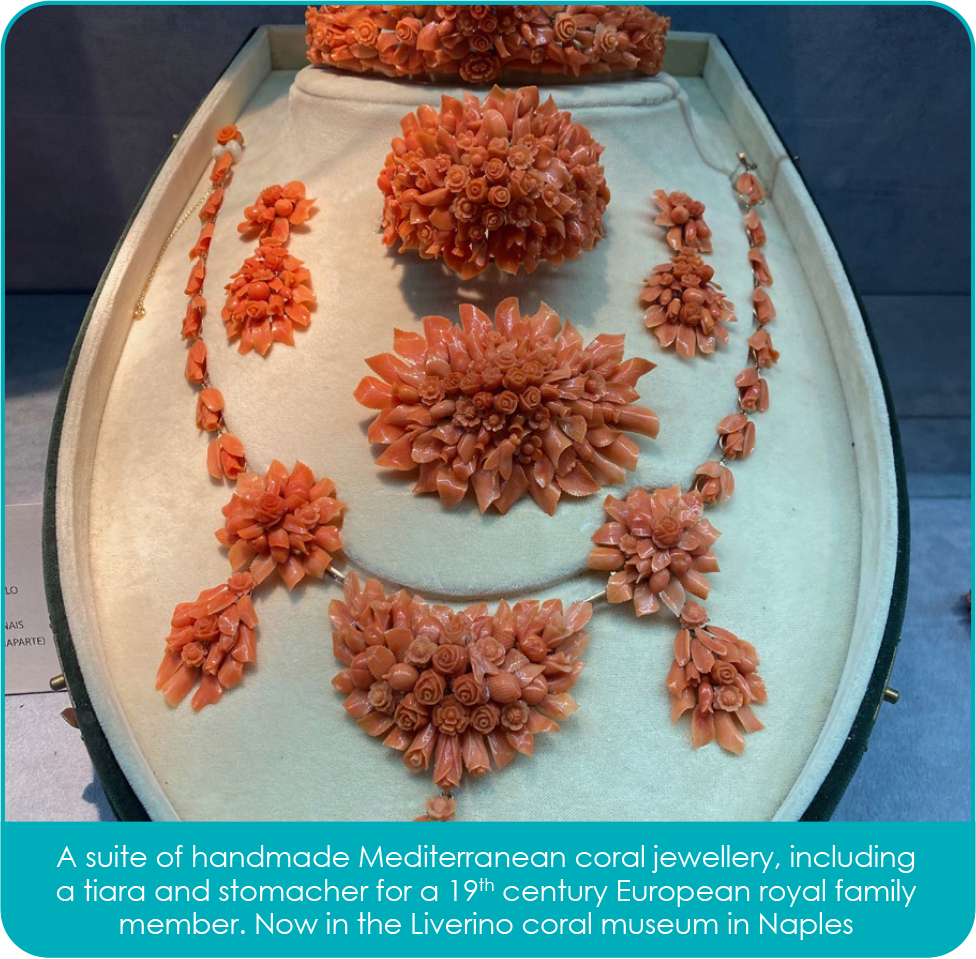

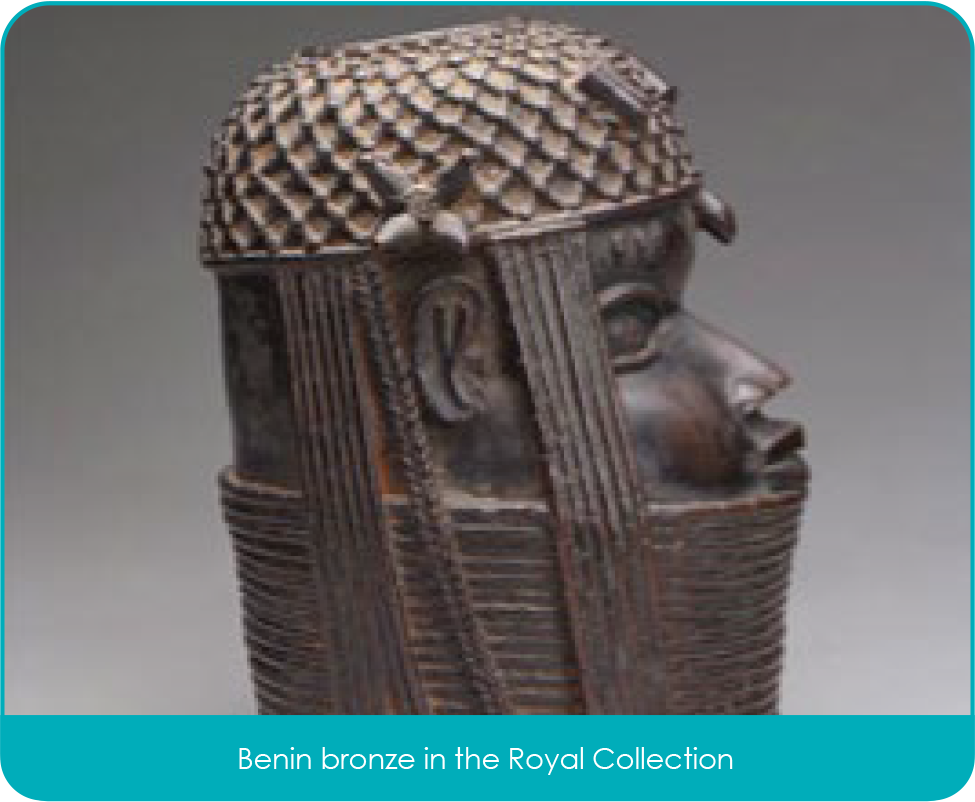

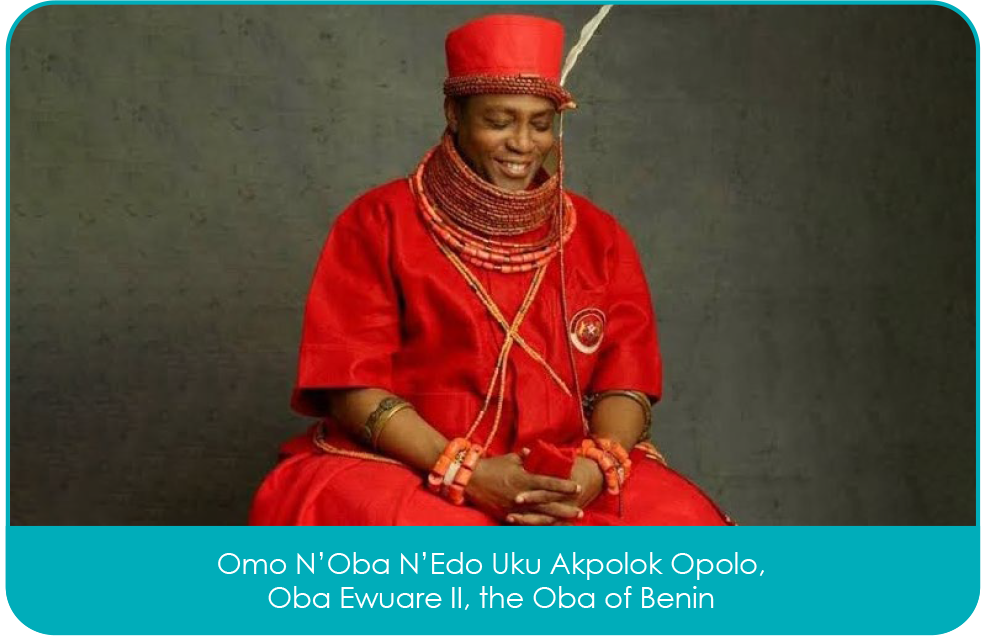

Did you know that coral was used in Rome as early as 1500 BC? It has been used as amulets in the Catholic faith for centuries and revered in Buddhism. To this day it is an expression of status and wealth in Benin in Africa, Poland and Ukraine and it has been used as currency across the world.

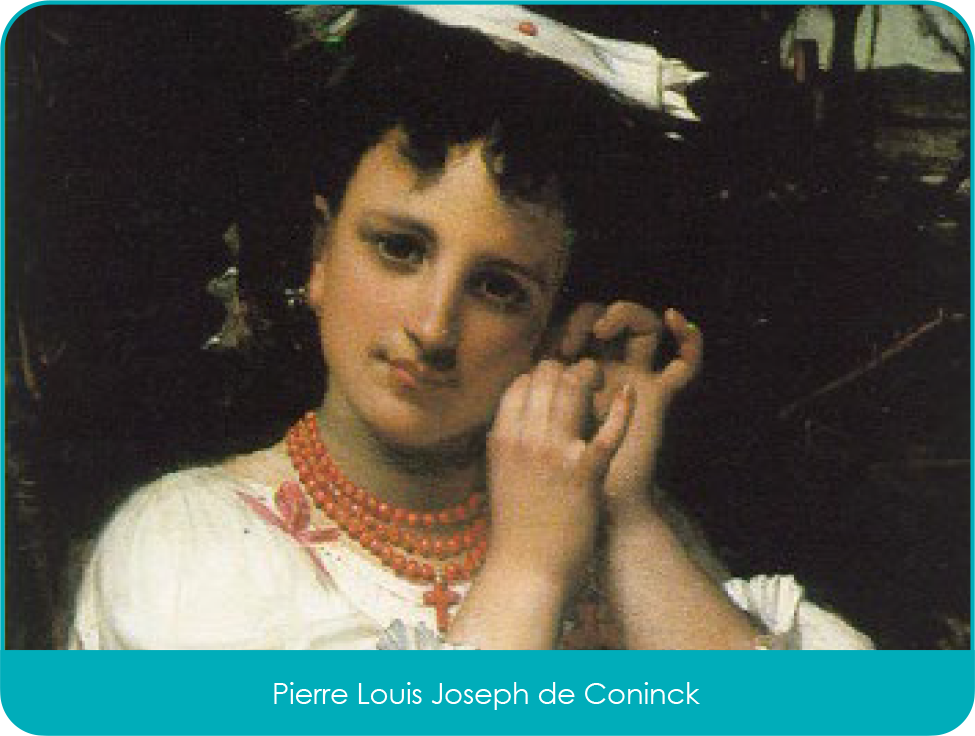

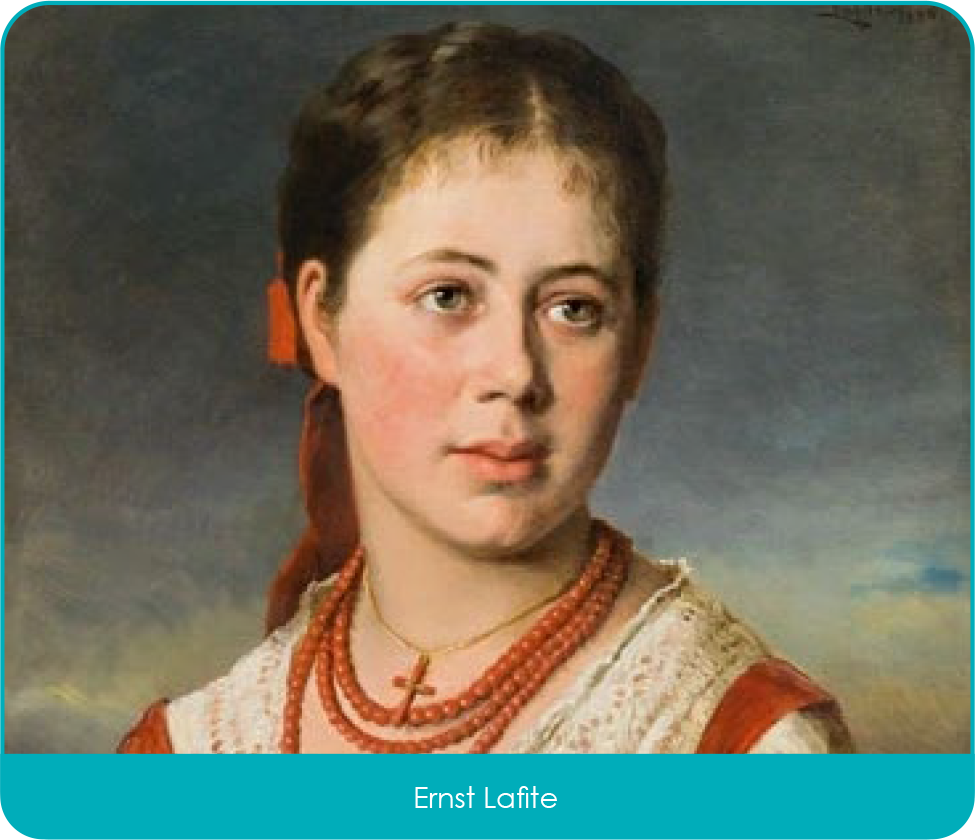

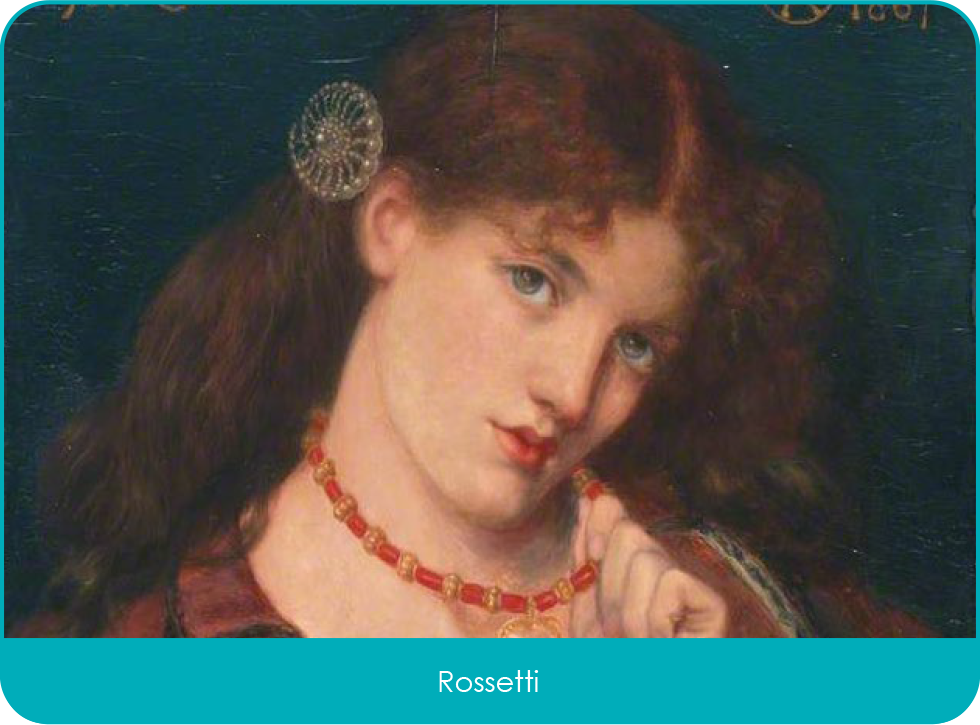

In the Mediterranean, coral harvesting has been documented since the 15th century and its secrets and systems were passed down through each generation of a family. This industry was particularly buoyant at Torre Del Greco, a beautiful fishing village on the slopes of Vesuvius. Which for decades in the 1800’s saw almost every local family involved in the coral trade in some form from diving to forming the beads to selling the strings of coral. This development and success of the coral industry at Torre del Greco was arguably thanks to Ferdinand IV of Bourbon, who worked to regulate the fishing of coral from this area of Naples and protect local jobs. He recognised the huge demand for beautiful coral jewellery and religious accessories, the ownership of which was seen as a status symbol across Spain, Italy, Poland and Ukraine, which lasts to this day. Look through several Old Master paintings and you may well find coral pieces to denote protection and wealth.

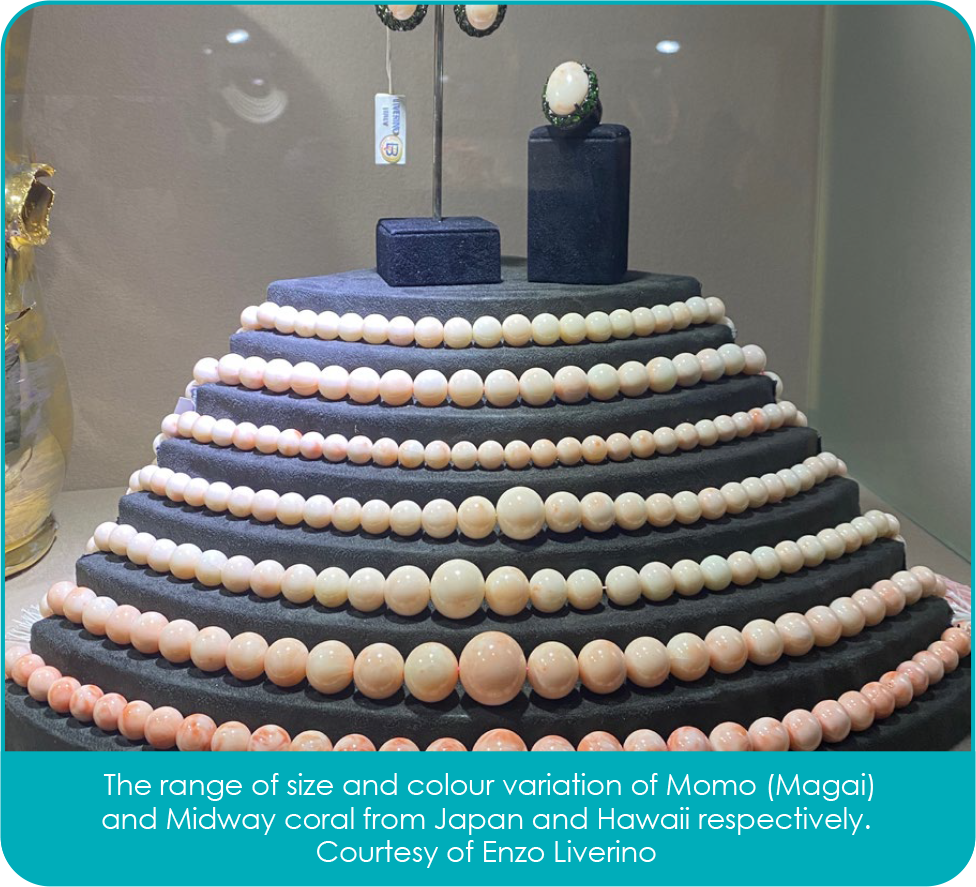

Even good things come to an end and the Mediterranean monopoly on coral supply was to change in the 1870’s when a different species of coral, ‘Momo’ coral was discovered in Japan and later in Taiwan and Hawaii. These finds would open up coral appreciation to the world and the largest market for coral is now the Far Eastern market.

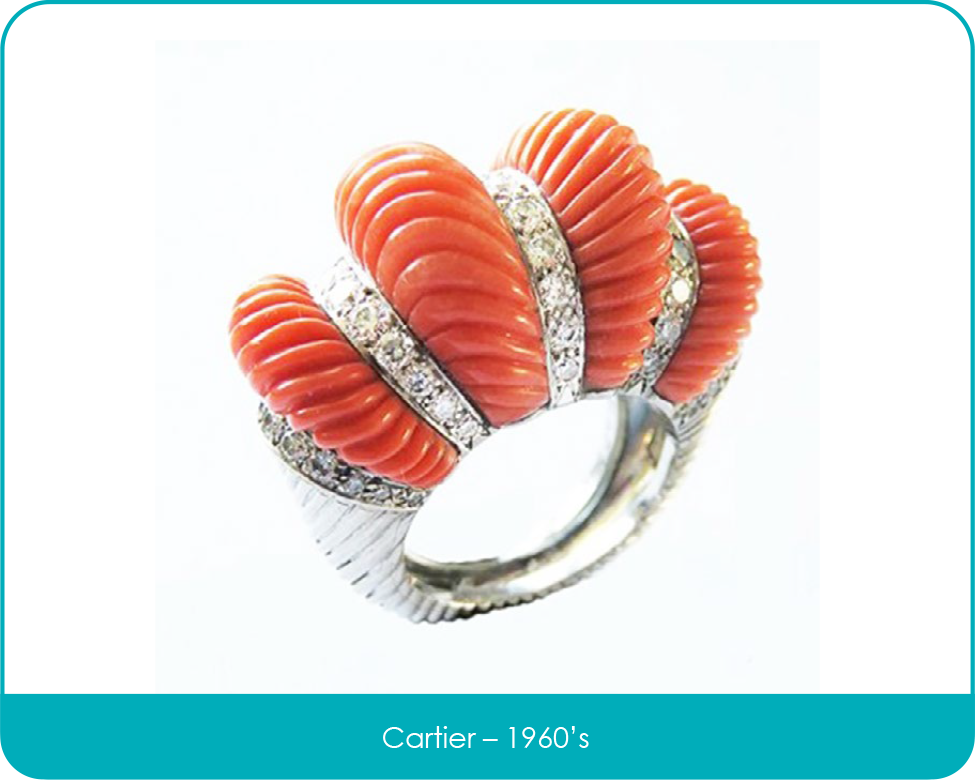

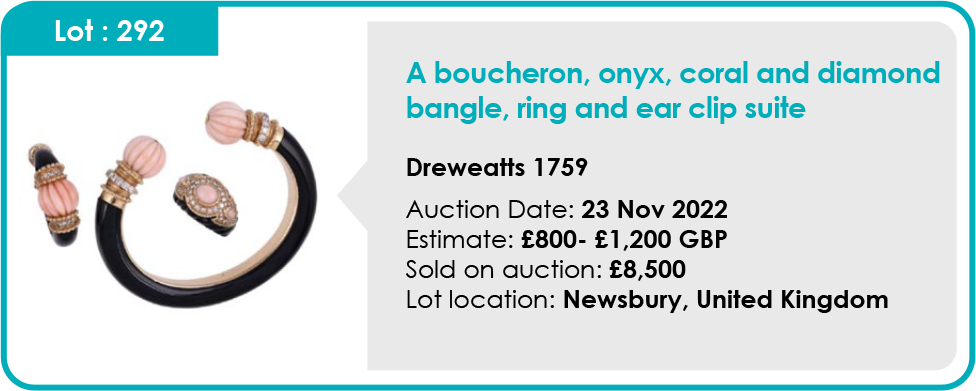

Collectors are starting to wake up to the beauty of coral that Cartier and Van Cleef and Arpels have been giving to their high net worth clients for over a century.

Precious coral, particularly antique and vintage pieces, are becoming very sought after and gaining good prices at European auctions. Keep an eye out for depth of colour and condition, and a smattering of diamonds is always nice too.

Did you know that the size of coral necklaces depend on the type and size of coral branch? Mediterranean coral can grow up to eight millimetres in diameter, however Midway coral from Hawaii up to 20 millimetres. Each piece of harvested coral from deep in the ocean is cleaned, divided and polished by hand into perfect beads, then matched into earrings and necklaces. It can take over a year to make a larger sized necklace.

There is a huge market in China and the Far East for the top quality Oxblood and Momo coral pieces. So much of the finest coral will make it’s way there and prices rival that of fine jade.

However, you may well have vintage pieces in your jewellery box and I strongly suggest you review their value. It may just surprise you.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.