Over the last few days auctioneers Sotheby’s held what could be described as “the sale of the century” – the collection of the late British rock music icon Freddie Mercury.

Rarely has auction captured the public imagination so powerfully. Sotheby’s dedicated their entire New Bond Street galleries to a month-long preview of the sale, aptly titled ‘Freddie Mercury: A World of His Own’.

The demand has been unprecedented. Almost 150,000 people of all ages and nationalities visited the saleroom to attend the preview, often patiently queuing for over two hours. For many the viewing appeared to be a pilgrimage to pay tribute to Freddie and his career, for others a chance to see a blockbuster event at the intersection of art and celebrity. Freddie’s influence goes far beyond the boundaries of music, he has become a cultural cornerstone, style idol, and one of the definitive figures in British music history.

Freddie left his entire collection (as well as his home Garden Lodge) to his dear friend Mary Austin. Mary has carefully preserved these pieces since Freddie’s untimely death in 1991.

Mary has described having taken the “difficult decision” to sell the collection this year. Due to Freddie’s appreciation for Sotheby’s, the company was chosen as the sale venue. Freddie famously said (as quoted in the book accompanying the sale) “The one thing I would really miss if I left Britain would be Sotheby’s”. Those who knew him speak of Freddie continuing to visit Sotheby’s until a few days prior to his tragic passing.

The sale offered a genuinely unique insight into the private life of the star. The auction of over 1,400 lots was held over six separate sale days. The sessions were arranged to reflect both Freddie’s public career and private collection. Freddie was an avid collector with a keen eye, the different sale days aimed to reveal this. Freddie’s love of Japan, his devotion to his cats, flamboyant wardrobe, appreciation for antiques, dedication to his craft of song writing and success as a member of Queen were all apparent.

The work of instantly recognisable artists and manufacturers were included throughout: Cartier, Tiffany, Lalique, Faberge, Dali, Picasso, Miro to name but a few. Those pieces closely associated with Queen and Freddie Mercury’s career as a singer and songwriter generated some of the strongest prices.

Bidding was fierce during every day and across all areas of the sale – with buyers from across the globe clamouring to own a piece of the Freddie “magic”. Almost all the pre-sale estimates were far exceeded and on some occasions by over a hundred-fold!

I will now take the opportunity to give an overview of each sale day and its highlights.

Day One: The Evening Sale

The Evening Sale was a microcosm of the collection – some fifty-nine lots including major highlights in art, design, jewellery, lyrics, instruments, and stage costume. The atmosphere unlike a typical Sotheby’s evening sale – the packed saleroom crowd seemed there to celebrate Freddie’s life.

The auction started as it meant to go on – Lot 1, the door to Freddie Mercury’s home the Garden Lodge took almost 25 minutes to sell. The green painted door was a London landmark – the exterior entrance to Freddie’s private residence. Now more like a piece of contemporary art having been heavily graffitied by visiting fans. The reverse in contrast was cleanly painted in jade green. The pre-sale estimate of £15,000 – 25,000 was quickly surpassed. The hammer eventually fell at £325,000 (including buyer’s premium £412,750).

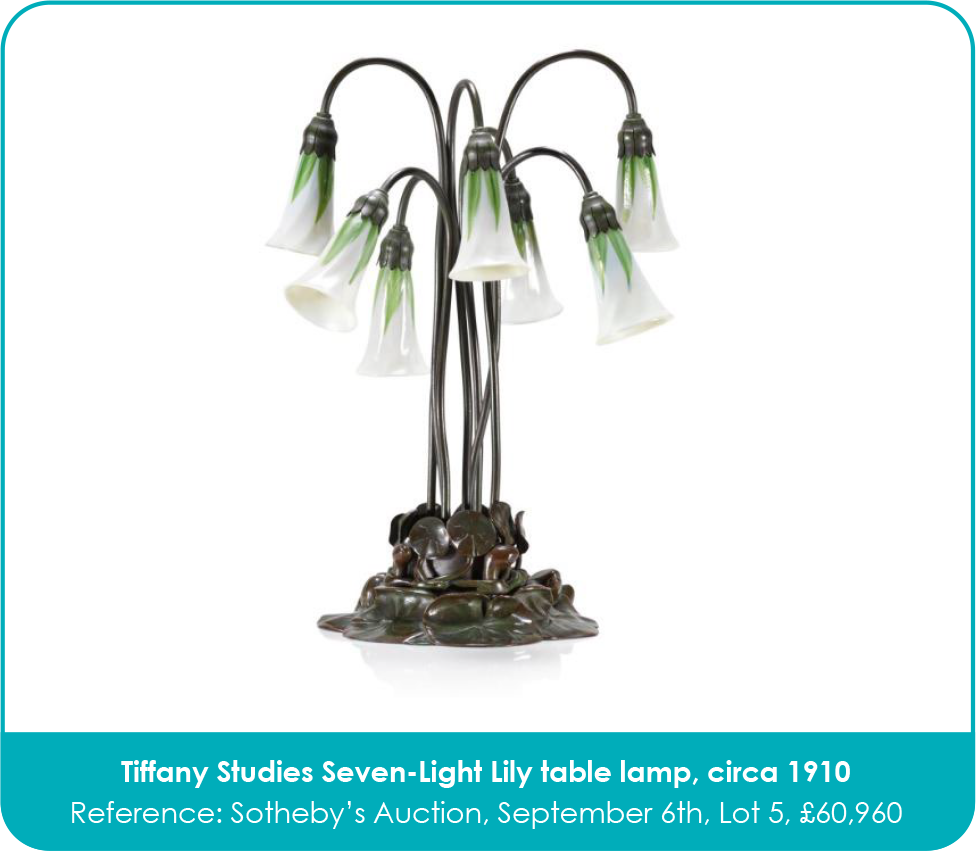

Several important pieces reflecting Freddie’s appreciation of Art Nouveau were offered. One of the most striking was the Tiffany Studios seven-light Lily table lamp. Designed circa 1910, it showcased the skill of Louis Comfort Tiffany in producing beautiful products using relatively new technology. The piece was offered with a pre-sale estimate of £8,000 – 12,000 – the final sale price including buyers premium £60,960.

Another Art Nouveau piece of note was lot 6, a gold and jewel mounted agate vesta case created by Faberge. The vesta had been purchased by Freddie from an auction held at Sotheby’s Geneva in May 1991. It sold for a total of £95,250 (including BP, estimate £6,000 – 8,000).

Freddie’s appreciation for Japanese art and design is well known and Sotheby’s dedicated an entire day to this element of the collection. The key piece of Japanese art within the Evening Sale was a woodblock print ‘Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohasi Bridge and Atake’ by Utagawa Hiroshige. The catalogue detailed how Freddie and Mary Austin had sourced the woodblock during a visit to Japan in the 1970s. The estimate of £30,000 – 50,000 indicated the importance of the work, it sold for a total of £292,100 (inc BP).

Jewellery from Freddie’s personal collection generated some of the strongest bidding of the evening. The German silver snake bangle, notably worn by Freddie in the Bohemian Rhapsody music video (as well as numerous other appearances in the 1970s) was estimated at £7,000 – 9,000. Arguably one of the most iconic lots offered in the sale, the hammer eventually fell at £500,000 (£698,500 inc. BP). Another piece of note was Lot 32 an onyx and diamond ring by Cartier. The jewel, reputedly a gift from Elton John to his close friend Freddie, was sold with an estimate of £4,000 – 6,000. The total selling price (inc BP) was £273,050 with 100% of the hammer price being donated to the Elton John Aids Foundation.

Many of Freddie’s biggest fans and most passionate collectors awaited the lots closely associated with his craft as a song writer. Lot 42 was the extremely important signed eight-page manuscript lyrics for ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. Queen’s most ground-breaking and recognisable song is now a standard of popular music. The manuscript offers a deep insight into Freddie’s process in writing it. The importance of the work was indicated by the pre-sale estimate of £800,000 – 1,200,000. The total selling price was £1,379,000. Lot 44 Freddie’s Yamaha grand piano had been acquired by the star in 1975. The treasured instrument was used to composed many of Queen’s most famous songs and entertain guests at his home. With an estimate of £2m – 3m, prior to the auction Sotheby’s announced it would be offered without reserve. It eventually sold for slightly below the low estimate at £1,742,000.

Lot 57 was perhaps the most recognisable of the stage costumes available. Freddie’s crown and cloak worn on the ‘Magic’ tour during June – August 1986. The outfit had featured in much of the advertising and publicity for the auction. This regalia fit for a king achieved £635,000 (inc. BP – est. £60,000 – 80,000).

The final evening sale total was over £12 million.

Day Two: ‘On Stage’

The second day of the auction concentrated on Freddie Mercury’s professional career as a performer and musician. Costumes, awards (including Gold Discs), rare vinyl and lyrics were all on offer. This area of the sale had been a clear draw with fans during the sale viewing.

Lot 240 a military style jacket created for Freddie and worn at his 39th birthday party in September 1985 (and again worn later the same year at the finale of Fashion Aid) garnered much advanced bidding online. Against an estimate of £12,000 – 16,000 the final total selling price was £457,200.

Gold Discs Sales Awards are always in high demand with collectors, especially when the recipient is the composor. Freddie’s disc collection was a major feature of the auction viewing layout and all sold well. The RIAA Gold Disc presented to Freddie for sales of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ sold for £114,300 (est £4,000 – 6,000).

Lot 110 was one of the most important lots in Queen’s iconography – a collection of Freddie’s pen and ink designs for the band’s logo. The group of drawings included the final version of the iconic insignia. The lot achieved £190,500 (est £8,000 – 12,000).

The total realised for the second day was over £9.4m

Day Three: ‘At Home’

The third day of the sale was comprised of over 250 lots. ‘At Home’ offered the clearest indicated as to Freddie’s interior design style and passion as a collector. The auction resulted in a World Record price for the work of artist Rudi Patterson (British-Jamaican, 1933-2013). Whilst German porcelain, French glass, Chinoiserie inspired objects and furniture, works by Erte, and Icart all featured in number.

Lot 501 was probably one of the most surprising. A 20th century Chinese armchair carved with a dragon motif was estimated at an affordable £300 – 500. The piece was one of Freddie’s first acquisitions – it eventually sold for an astonishing £44,450.

One of the most stylish musical instruments offered during the six days was lot 524 Freddie’s grand piano (and matching stool) by John Broadwood & Sons. The piano in elegant Chinoiserie case was manufactured circa 1934 and purchased by Freddie during the 1970s. Considering the price realised for Yamaha piano sold during the Evening Sale, the estimate of £40,000 – 60,000 for the Broadwood appeared rather modest. Bidders agreed and the final sale total here was £444,500.

Within the Lalique collection, lot 571 the stunning blue Perruches vase, was a highpoint. Designed in 1919 it sold for £34,290 (est £4,000 – 6,000).

The humble auction catalogue was also highly prized. Lot 665 being one such example -the collection of annotated Sotheby’s, Christies and Bonhams 1991 sale catalogues (with invoices) sold for £12,700 (estimate £200 – 300).

Several items of furniture designed by Robin Moore Ede, who worked closely Freddie on the interior of Garden Lodge, were highly desirable. Indicative of Freddie Mercury as host, lot 650 Freddie’s D-shaped bar sold for £120,650 (est. £6,000 – 9,000).

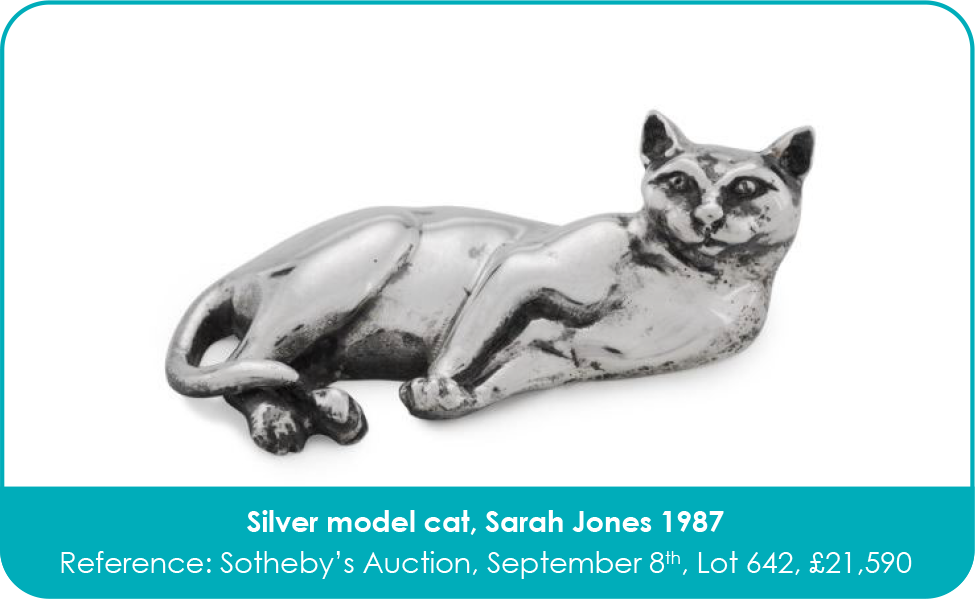

Finally for feline fans lot 642, a silver model of a cat by Sarah Jones, dated 1987 had a pre-sale estimate of just £100 – 150. The lot sold for £21,590.

The eventual total for the third day was just over £5.3 million.

Day Four: ‘In Love with Japan’

The fourth day focused entirely on Freddie’s Japanese collection. His love affair with the Japan began in 1975 and continued throughout his life. The sale of 200 lots, included 37 lots of woodblock prints, 56 lots of kimonos, as well as decorative ceramics, silver, lacquer work and cloisonne.

Within the woodblocks Lot 1029 Ito Shinsui’s ‘Woman Wearing an Undersash’ reflected both Freddie’s love of kimono and Japanese prints. The beautiful scene sold for £38,100 (est. £1,000 – 1,500).

Several decorative boxes were included, part of the collection of traditional crafts or kôgei that Freddie treasured. The highest priced piece here was for lot 1056, a Taisho period document box by Wajim Keizuka selling for £76,200 (the estimate £4,000 – 6,000).

Lot 1063 an Ando style vase was one of the most desirable pieces of cloisonne. Decorated with koi carp and produced during the Meiji / Taisho period it was estimated at £1,500 – 2,000 but eventually sold for £57,100.

Freddie wore kimono at home and on stage and they served as presents for friends. The leading kimono in the collection (lot 1162) had been displayed prominently in the galleries. This decorative garment was offered at £1,200 – 1,800 with the final sales price reaching £27,940.

The Japanese collection final total was over £2.6 million.

Day Five & Six: Crazy Little Things 1 & 2

Potentially the most affordable lots of the sale were the offered during two online auctions titled ‘Crazy Little Things’. Bidding was available for over a month allowing interested spectators to see prices creep higher and higher.

Almost 700 lots were sold during these two auctions. Several items were estimated at levels almost unheard of for Sotheby’s since the 1980s. However, Freddie fever had now taken hold and bidding was not for the faint hearted.

Part 1 contained additional property from Freddie’s home. Cats featured heavily. Lot 1502 was described humorously as ‘a motley group of feline ornaments’. The clowder included twenty-nine in total and appeared to have been amassed by Freddie over several years.

They had been estimated at £300 – 500, a low estimate of a little over £10 each. The collection sold for £30,480! Similarly, lot 1513 a dish in the form of a cat was estimated at a meagre £40 – 60. Manufactured by Americn company N.S. Gustin the online bidding ended at £12,065 (inc. BP).

Lot 1782 Freddie’s 1982 BT red plastic rotary phone my well have been a world record price. Against an estimate of £1,000 – 2,000 it achieved £8,890.

Freddie’s decorative shower door, emblazoned with his initials was sold as lot 1794. The striking bathroom accessory reached £12,700 (est. £500 – 700).

Part 2 focussed on Freddie as a performer, with most of the lots being awards, ephemera and clothing.

Again, awards relating to ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ were amongst the most esteemed. Lot 2039 the British BPI Award for sales of over 500,000 copies sold for £152,400 (est. £3,000 – 5,000).

Freddie’s aviator sunglasses had been offered with a guide of £2,000 – 3,000. However, such a recognisable piece would always be prized. The selling price here was £40,040.

Finally, to (possibly) the most talked about lot of the auction – the penultimate item in the sale lot 2348 Freddie Mercury’s silver Tiffany & Co. moustache comb. A replica or Freddie’s famous moustache had hung above the entrance way to Sotheby’s London headquarters for over a month – a symbol of the star. With an estimate of only £400 – 600 the virtual hammer fell at £152,400.

The combined total for ‘Crazy Little Things’ was over £10.3million bringing the total for the entire event (including buyer’s premium) to just under £40 million.

Rachel Doerr spoke with Mike Moran, English musician, songwriter, composer and record producer, following the auction who said ‘Wonderful but strange experience to see many of these treasures somewhere other than beautiful Garden Lodge. Spotted a couple of presents I’d given Freddie as Christmas and birthday presents plus some of my scribbled music and lyrics for the Barcelona lots which went for a bit over £157,500.(wish I’d kept a couple!)’- Mike Moran Sept 15, 2023

Mike Moran studied at the Royal College of Music in London prior to becoming a session musician and a composer and arranger. Moran has worked with many musicians, including Ozzy Osbourne, George Harrison and various members of Queen. He was co-producer, arranger, keyboards performer and co-author of all the tracks on the album Barcelona, the classical crossover collaboration between Freddie Mercury and opera singer Montserrat Caballé, released in 1988.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

In the mid-15th Century cutters designed the table cut diamond, they used the same polishing methods and simply removed the top point of the octahedral shape to produce a table.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

After developing and perfecting table and rose cuts, European cutters started to experiment with new cuts and styles. Cardinal Jules Mazarin requested that cutters in Europe designed a faceted diamond. The result was a cushion shaped diamond with 34 facets called the Mazarin cut, also known as the double cut.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The mid-17th century saw the introduction of the single cuts. Like the point and table cut, the single cut resembled the shape of the octahedral rough. It also displayed more potential for brilliance than the table cut because it had more facets. This cut served as the basis for the modern brilliant cut and even today, the single cut is still used on smaller diamonds.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.

The new rough from Brazil was used to create the first old mine cut also known as the Peruzzi Cut; this has the same number of facets as the round brilliant, but with a high pavilion it resembles a cushion shape. In 1750, a London jeweller called the new style of cut a passing fad and said the classic rose cut would outlast them all.