Recently two of our specialists have been exploring some of the London art exhibitions – Photo London 2025 and the Affordable Art Fair. Here is their experiences in their own words:

Ashley Crawford, Asian Art Specialist

Recently, I attended the annual Affordable Art Fair in Hampstead (one location of several worldwide taking place throughout the year) to explore artworks by Contemporary Asian artists, both living in Asia and throughout the diaspora. The Affordable Art Fair generally sells works up to approximately 7,500 GBP and often below 1,000 GBP. This event is not only a great way to support living artists, but is also an opportunity to observe wider art market trends and discover up-and-coming artists locally and from around the world.

My first stop was TNB Gallery, a Korean Contemporary art gallery. I was immediately drawn to a series by Jeong Oh, who is known for her mixed media depictions of traditional antique Korean moon jars. Her series Holds All Good Things uses mother-of-pearl to depict the smooth, white glaze of moon jars with touches of color in a way that makes the jars particularly contemporary, while paying homage to their antique Korean heritage. Mother-of-pearl has also long been used in various Korean art forms. The three dimensionality and presence of mother-of-pearl means that these works appear different when viewed from various angles. The addition of gold creates a touch of drama that is otherwise absent from traditional moon jars. Oh’s larger works have recently been offered for roughly 7,500 GBP – 20,000 GBP, but her smaller objects on display at the Affordable Art Fair were all listed at about 1,000 GBP or under. For collectors searching for actual ceramic moon jars, they will be spoiled for choice; this ceramic form dates from the late 17th century, with many contemporary renderings and antiques from the centuries in between. The most famous Contemporary moon jar artist is Young-Sook Park. Although his works are not the most affordable, there is ample modern-day production of this beloved Korean art form to suit a wide range of budgets.

Next, I visited Hanoi Art House, which specializes in Contemporary Vietnamese art. Contemporary Southeast Asian artists have typically been underrepresented in London (especially compared to Paris), even within Asian art circles, but the Affordable Art Fairs in Battersea and Hampstead have consistently showcased living Vietnamese artists over the past several years. My favorite works at Hanoi Art House were lacquer-on-wood paintings by Bui Trong Du, who is best known for his depictions of Vietnamese women in traditional dress, often in nature and amongst birds. The ladies’ dresses are intricately decorated. Like Jeong Oh, Bui Trong Du draws on his cultural heritage to inspire his Contemporary renderings, as Vietnamese lacquer dates to at least the 4th century BCE. His works are typically offered for 500 GBP – 9,000 GBP. The works on display at the fair were within his more affordable range.

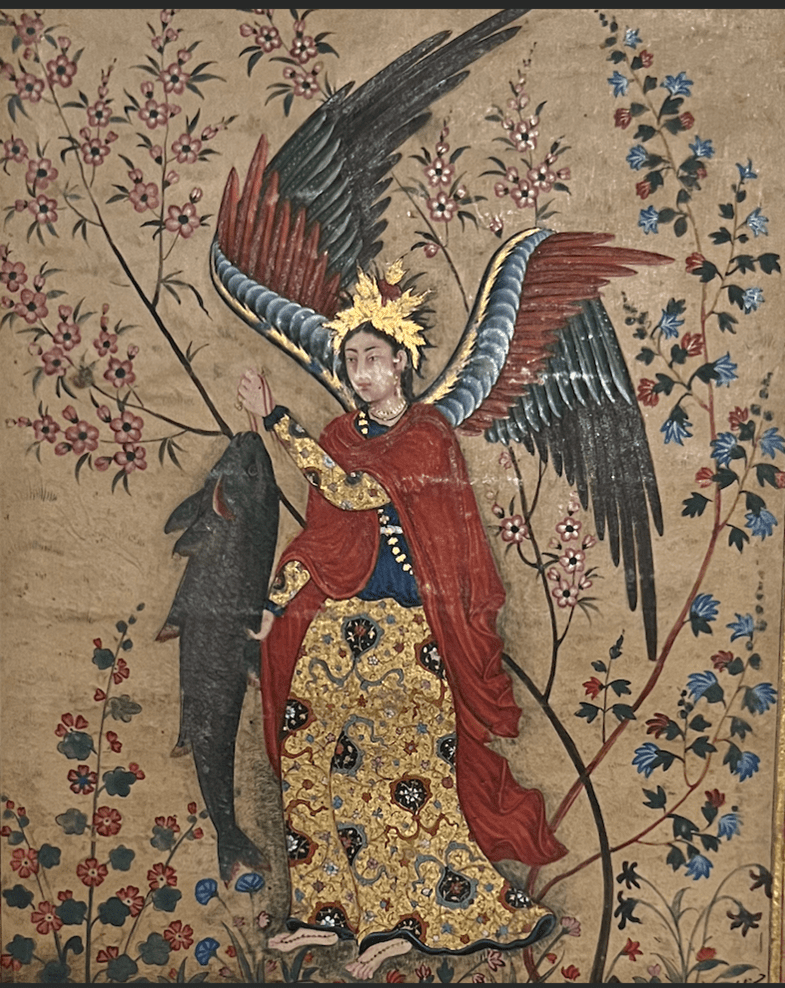

Lastly, I visited the UK-based Anrad Gallery, which showcased South Asian artists. The highlight of this exhibit was a series of Pichwai paintings by Contemporary artist Sushil Soni. Pichwai is an antique Indian tradition of painting on cloth, depicting Krishna’s Leelas (divine exploits) on temple walls. This practice dates back four centuries. As with the artists at the other galleries discussed here, Soni takes a beloved artistic tradition and breathes new life into it. Anrad Gallery displayed twelve paintings from Soni’s series Baraah Maas (Twelve Months) (2022). Each individual work was listed for 975 GBP. His larger works can be offered for around 1,000 GBP, so these fall within his typical range.

Pictured above is a vibrant scene of a Holi celebration, again, emphasizing and celebrating India’s cultural heritage.

There is something at the Affordable Art Fair for everyone. I was pleased this year with the continued presence of Asian artists and look forward to returning to the next fair in Battersea this October!

Contemporary Art Specialist Ben Hanly:

The first two weeks of May are busy ones in the London art scene, with 2 very different fairs opening their doors to London’s art loving audiences.

The first fair to open from 7th-11th May, is the Affordable Art Fair, which first launched in London’s Battersea Park back in October 1999. The founding philosophy of the fair was, and still is, to democratise the buying of art – to make the experience easy, accessible and affordable to the general public who often assume that buying art is for ‘other’ people and not themselves. The fair has been roaring success and has now grown into a veritable leviathan with fairs in 13 cities worldwide, including 3 in London at Battersea Park (October and March) and 1 at Hampstead in May.

The May edition in Hampstead Heath had everything one comes to expect from the AAF, with 106 galleries exhibiting and displaying works of art starting at £100 and maxing out at £10,000. Turner prize-nominated David Shrigley was among those showing work, with 106 galleries showcasing contemporary paintings, prints, ceramics, sculpture and photography.

This year the Fair invited artist Claire Knill (represented by Lara Bowen Contemporary) to be the fair’s official installation artist. Knill’s large-scale geometric work, Willow Tree, which took centre stage in the main atrium, transforming the space with movement, light, and reflection. The work focusses on the connection between art and mental well-being.

Sessions this year include Summer Lates, where ticket holders can enjoy live DJ sets with a drink in hand while browsing the fair for new art pieces, and family mornings with free activities from painting workshops to face painting.

There is no denying the huge impact that the AAF has had on the international Art Fair landscape. More prestigious fairs may judge it as being too entry level and decorative, however, none can knock its enduring appeal. Similarly, all international art fairs have taken a leaf out of the AAF’s book and put increasing effort and money into developing exciting engagement programs and talks with the aim of appealing to new collectors.

Photo London, which ran from 15th-18th May, is London’s premier photographic fair which brings the finest international photography to the British capital every year. Staged at Somerset House the home of the Courtauld Galleries, the Fair presents the best historic and vintage works while also spotlighting fresh perspectives in photography. Along with a selection of the world’s leading photography dealers and galleries Photo London’s Discovery is dedicated to the most exciting emerging galleries and artists. In addition, each edition sees a unique Public Programme including special exhibitions and installations; and several Awards announced, headlined by the Photo London Master of Photography Award.

Beyond the Fair, Photo London regularly hosts Pre-Fair Talks engaging with the craft, market and knowledge of photography and acts as a catalyst for London’s dynamic photography community, with major institutions, auction houses, galleries and the burgeoning creative communities in the East End and South London presenting a series of Satellite Events.

This year the Fair marks its 10th anniversary in the capital, and with it, a new direction under the newly appointed Director, Sophie Parker, who was determined to move away from the clichés of pretty pictures of supermodels, artful murmurations of birds and majestic beasts and present something more serious, international and inclusive culturally.

By and large Sophie Parker has begun to achieve this. 100 galleries took stands in the Fair, ranging from small to large operations, all showing their finest works. At least half the exhibitors this year were foreign galleries, with an increasing presence from Asia. Well established galleries such a the Grob Gallery, showed superb examples by European greats such as Billy Brandt, Brassai and Brancussi; whilst GBS Gallery showed a strong selection of contemporary photography including ethereal landscapes by Harry Cory Wright and figure studies by the Canadian artist Laura Jane Petelko. There was a strong presence of Paris based galleries, including Galerie Bendana-Pinel who showed the work of Niccolo Montesei – one of the short-listed photographers of the Nikon Emerging Photographer Award, and Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière who showed beautiful nocturnal landscapes by the Paris based artist, Juliette Agnel.

The price pointing at Photo London was naturally higher than at the Affordable Art Fair, with prices starting at about £1,500 and reaching over £200,000 for a rare Brancusi photograph. Having said that, many wonderful things could be bought under the AAF’s top limit of £10,000, meaning that both fairs give new or modestly funded collectors the scope to start their own art collecting journey.

Today, as the fair marks a decade of operations, photography is firmly entrenched in the art world mainstream. Blue-chip galleries now routinely display photographic works alongside painting and sculpture at art fairs like Frieze and Art Basel. This shift was exemplified by mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth’s decision to represent Cindy Sherman in 2021—a bellwether event for photography’s ascent. Sherman, who began her career in the 1970s, was long overlooked by major art fairs but now shares gallery representation with icons like Louise Bourgeois and Philip Guston. In 2023, fellow mega-gallery Gagosian announced its representation of Nan Goldin and brought original prints by Francesca Woodman to Art Basel, alongside personal works by the fashion photographer Richard Avedon.

Together, the Affordable Art Fair and Photo London highlight the breadth and depth of London’s art scene this May – from accessible, playful pieces to museum-quality photography. Whether you’re starting your collection or expanding it, there’s no shortage of opportunity to engage with art that resonates, challenges or simply brings joy.

To arrange a valuation of your art or photographs, give us a call on 01883 722736 or email us at [email protected].