(From COIN Private Finance working in conjunction with Doerr Dallas Valuations)

If you own a piece of fine art, it can be a financial asset as well as an object of pleasure. You can raise capital without selling your artwork, thanks to art lending.

Detail from Untitled (1982) by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Photograph: Sotheby’s/EPA

In this article we have worked together with COIN Private Finance to explain exactly what art lending is, who uses it and why, and the kinds of art that can be used for loans. We also talk you through how it works, step by step. If you have artworks and want to release capital without selling them, read on to find out how.

What is art lending?

Art lending is when a work of art is used as collateral for a loan. This form of lending is becoming increasingly popular as it allows art collectors to release liquidity from a painting or print, without having to sell it. The market for art-secured loans has grown consistently over the past decade and there are now an estimated US$24 billion of outstanding loans against art (according to the Deloitte Art & Finance Report 2019).

Art Finance is traditionally associated with ultra-wealthy collectors being offered loans by big private banks or auction houses. However, the market has expanded and diversified over recent years, and collectors at all levels are using their art as collateral. Anyone who owns a valuable work of art can raise finance through a boutique, specialised art lender.

Why use art lending?

Detail from Untitled (1982) by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Photograph: Sotheby’s/EPA

There are two main reasons why collectors take out a loan against a work of fine art. The first is if a collector needs to raise finance quickly, whether to inject cash into a business or settle unexpected bills. Selling art can be a lengthy and complicated process, whereas art loans can be arranged in a matter of days. The second reason for choosing to borrow against art is to release capital for other investment opportunities, whether that’s another work of art, property or a business venture.

With the economic uncertainty brought about by Covid-19 and Brexit, taking out a loan against art has become an even more appealing proposition to collectors. A loan allows collectors to leverage their artwork while waiting for the optimum time to sell; it offers a fast route to capital, whether that’s needed to cope with unforeseen events, or to be strategically redeployed into higher-yield investments.

What kinds of art can be used for loans?

Any artwork that is likely to fare well at auction can be considered for a loan. Post-War and Contemporary works are particularly attractive as they have performed particularly well in auctions in the last few years.

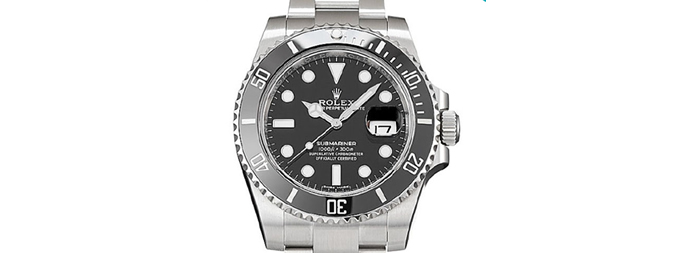

Substantial loans have been taken out against works by superstars of the contemporary art scene, including a $10 million painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The New York prodigy received huge acclaim in the 80s, and has posthumously set auction records: in 2017, Untitled (1982) was sold at Sotheby’s for a staggering $110.5 million.

Works by the elusive British artist Banksy are also reliable assets for art-secured loans. The world’s most infamous graffiti artist has become an art market phenomenon, and his works regularly exceed auction estimates. Commercial works, such as editions of screen prints, can be authenticated with a certificate from “Pest Control” – the body set up by Banksy to verify genuine works.

At Coin, we consider fine art from all periods, from Old Masters to Contemporary. Our experts are qualified to appraise a range of works, including paintings and prints, sculpture and ceramics.

How does it work?

As experienced art lenders, we ensure that our process is simple, transparent and discreet.

First, our art market specialists will appraise the work, and any accompanying documentation relating to its provenance, such as invoices and purchase histories.

Once the artwork has been valued, we’ll liaise with you to create a loan agreement that suits your needs and circumstances. Our typical Loan To Value (LTR) is 50-70% and we can offer terms to suit you, from just one month to one year. As we offer non-recourse loans, only the work of art itself is used as collateral and we do not run any credit checks. Once the terms are finalised, you will receive a secure loan agreement, laid out in clear terms with no hidden fees.

Following receipt of the signed agreement, we will arrange a convenient time for collection. Your artwork will be professionally handled at all times and stored in our climate-controlled facility for the duration of the loan.

Upon repayment of the loan, the artwork will be safely and securely returned to you.

Coin case studies

Damien Hirst artworks

Detail of Noble Path from Mandalas (2019) by Damien Hirst. Photograph: Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. DACS 2019.

We were approached by an Art Advisor whose client was looking to finance a property deal. The client had a private collection of Damien Hirst artworks, which is an ideal asset for raising capital quickly.

Our art experts valued the pieces and we offered the client a loan within 72 hours. The open market value of the collection was £400,000, and we were able to offer a loan value of £210,000. We agreed terms with the client: a 2% fee and 2% per month for a 3-month period. The loan was completed in just six days.

Thanks to the speed and simplicity of our process, the client was able to seize liquidity, make the property deal, and hold on to their precious Damien Hirst collection.

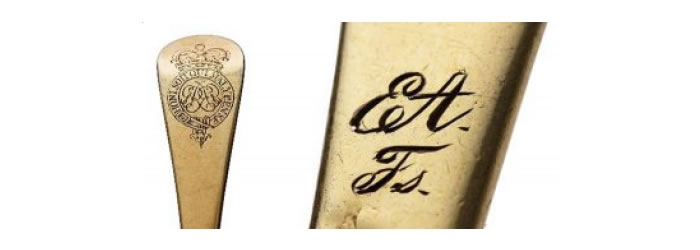

Charles Rennie Mackintosh furniture

Willow Chair by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Photograph from https://www.thereviewmag.co.uk/charles-rennie-mackintosh/.

A client approached us with a piece of vintage furniture by Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The item was due to be sold at a prestigious auction house – however the sale was not due to take place for another five months.

The client needed liquidity right away, which is why they came to Coin. We organised a sale advance on the item, funding 50% of the auction mid-estimate, over the five-month period until the sale. The furniture was valued at £125,000, and we offered a loan of £60,000, charging the client 1% per month and a 10% hammer fee.

The client was able to raise instant finance while waiting for the right moment to get the best price for the piece at auction.

Apply for an art loan

To apply for a secured loan against your art, please complete the online form on our website, or email [email protected] with details and images of your assets. We’ll aim to respond within 2 hours.