The King James Bible first appeared in 1611. No special tribute was paid to it then, yet it became the ‘Authorised Version’ for English-speaking Protestants, universally read or listened to from the mid-18th century onwards.

Perhaps the secret of its success lay in its secure foundation in the work of William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale. Tyndale’s New Testament of 1525, the first English translation of the Bible ever printed, survives in one imperfect copy. Tyndale was burned at the stake in 1536. But all subsequent translations owed much to him, and ‘nine-tenths’ of the King James New Testament is said to be his work (David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography, 1994, p. 1).

Whereas Tyndale worked in isolation, the making of the King James Bible involved a massive collaborative and consultative effort. Some fifty translators were divided into six committees in the three locations of Westminster, Cambridge and Oxford. Each committee was allotted a different part of the Bible to work on, and given the same rules or guide-lines to follow.

Every translator but one was ordained and therefore familiar with Holy Scripture. Some were to gain rich benefices as a reward for their scholarly work.

James I played more than a nominal part in the Bible named after him. The son of Mary Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley, he became James VI of Scotland at the age of one in 1567, when his mother abdicated. He succeeded Elizabeth I thirty-three years later on 24 March 1603, becoming head of the Anglican church while already head of the Presbyterian church in Scotland.

The new king of England had hardly left his palace of Holyrood in Edinburgh on the journey to London before he received a Millenary Petition from a delegation of English puritans, this urged him to hold a conference in order to discuss religious abuses. The idea met with his approval, and the conference was convened at the Presence Chamber, Hampton Court Palace, on 14 January 1604. John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, seven bishops and five cathedral deans all came fully robed. A smaller group of four moderate puritans represented the opposition.

When John Rainolds, leader of the puritans, used the conference to stand up and make an unexpected petition for a new Bible translation, Richard Bancroft, bishop of London, argued that the Bishops’ Bible was sufficient for the Church’s needs and should remain in use. The Bishops’ Bible of 1568 was a revisal of the Great Bible of 1539, so called because a group of Elizabethan bishops had responsibility for it. Despite the wish of the church hierarchy to keep on using it, James’s imagination caught light at the thought of a new Bible dedicated to himself. He soon agreed to the proposal and actively involved himself in management of the project.

The fifteen ‘rules to be observed in translation’, surviving in several manuscripts, were drawn up by Bancroft in probable consultation with the king. Rule 1 expressed the precedence to be granted to the Bishops’ Bible. ‘The ordinary Bible read in Church commonly called the Bishops’ Bible’ was the text ‘to be followed, and as little altered as the Truth of the Original [Hebrew or Greek Septuagint texts] will permit’. However, in practice rule 1 tended to be ignored by the translators who freely ‘absorbed, copied, and adapted from any source they wanted’ (Adam Nicolson, Power and Glory, 2004, p.73). This was allowed by rule 14.

The Geneva Bible of 1560, familiarly known as the ‘Breeches Bible’, was an English translation by William Whittingham, Miles Coverdale, Anthony Gilby and other protestant exiles strongly influenced by John Calvin. Over 150 editions were published, illustrated with woodcuts. It was first published in England in 1575-1576, and became the first Bible printed in Scotland in 1579, where it proved highly popular. James I, who felt threatened by its anti-authoritarian marginal glosses, ordered a stop to further printings shortly after first publication of the King James Version (KJV). Robert Barker, the king’s printer, nevertheless continued to print the Geneva version surreptitiously, using the false date of 1599 for copies printed from 1616 to 1625.

The rules made no other attempt to exclude the Geneva version as a source. It was the first English Bible to be divided into chapters and verses, and the KJV followed the same divisions. Use of the Geneva text was actually encouraged under rule 14 which allowed all the earlier Protestant versions to be made use of ‘when they agree better with the [Hebrew and Greek] text than the Bishops’ Bible’; in practice its influence was ‘very considerable’ (Herbert p. 131).

One memorable turn of phrase which the KJV borrowed from it was St Paul’s ‘For now we see through a glass darkly’ (I Corinthians 13.12). On the other hand, there was no compromise on the issue of the hated marginal annotations. Rule 6 expressly forbad their use, allowing only short philological notes.

The six companies chosen for the translation did painstaking work through the years 1604 to 1608. The First Westminster Company, led by Lancelot Andrewes, dean of Westminster, a scholar of outstanding abilities, was given responsibility for Genesis up to the Second Book of Kings. John Overall, William Bedwell and Richard Thomson were all members of the same company. The dean of St Paul’s, Overall had taken part in the Hampton Court conference. Bedwell had become the country’s leading specialist in Arabic, a language which he rightly regarded as an aid to the understanding of Hebrew; he was vicar of All Hallows, Tottenham, from 1607. ‘Dutch Thomson’, so called because he was born in the Netherlands, was known for his drinking but also considered ‘a most admirable philologer’, equally at ease translating the Bible or the obscene epigrams of the Roman poet, Martial; Andrewes rewarded him with the living of Snailwell, Cambridgeshire.

for Genesis up to the Second Book of Kings. John Overall, William Bedwell and Richard Thomson were all members of the same company. The dean of St Paul’s, Overall had taken part in the Hampton Court conference. Bedwell had become the country’s leading specialist in Arabic, a language which he rightly regarded as an aid to the understanding of Hebrew; he was vicar of All Hallows, Tottenham, from 1607. ‘Dutch Thomson’, so called because he was born in the Netherlands, was known for his drinking but also considered ‘a most admirable philologer’, equally at ease translating the Bible or the obscene epigrams of the Roman poet, Martial; Andrewes rewarded him with the living of Snailwell, Cambridgeshire.

The task of translating some of the Bible’s finest poetry — the Book of Job, the Song of Solomon, and the Psalms — went to the First Cambridge Company. The first line of Psalm 23 had been translated as ‘The Lord is my shepherd: therefore can I lack nothing’ by Coverdale. The Company changed the line to ‘The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want’ with simple but profound effect. Its leader was Laurence Chaderton, the first Master of Emmanuel College, and one of the four puritans who had attended the Hampton Court Conference. Thomas Harrison, its most learned member, had studied Hebrew at Merchant Taylor’s School like Lancelot Andrewes but had much greater sympathy for the puritan cause.

Having been the person to propose the new translation, John Rainolds, President of Corpus Christi College, became the effective leader of the First Oxford Company. Entrusted with the final third of the Old Testament from Isaiah to Malachi, ‘this was the only company whose collective expertise rivalled Andrewes’s First Westminster Company’ (Gordon Campbell, Bible. The Story of the King James Version 1611-2011, Oxford, 2011, p. 52). Thomas Holland knew rabbinical as well as biblical Hebrew. Richard Brett’s languages were Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic and Ethiopic. Richard Kilbye ‘had an incomparable command of Hebrew sources’. Miles Smith, a scholar with no current university affiliation, possessed an extraordinary knowledge of Jewish exegesis and ancient languages.

Smith’s appointment as Bishop of Gloucester in 1612 suggests that his work was highly appreciated. Besides fulfilling his role for the First Oxford Company, he also sat on the Committee of Two, with Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester, the two acting as the Bible’s final revisers at proof stage. He contributed an anonymous preface to the KJV entitled ‘The Translators to the Reader,’ in which he declared that Bibles in all languages were consulted in the revisal process: ‘Neither did we think much to consult the Translators or Commentators, Chaldee [Aramaic], Hebrew,

Syrian, Greek or Latin, nor the Spanish, French, Italian or Dutch [i.e. German], neither did we disdain to revise that which we had done, and to bring back to the anvil that which

we had hammered’.

The Second Oxford Company, responsible for a large proportion of the New Testament, met in the rooms of Sir Henry Savile, the Warden of Merton College. Savile has been described as ‘the most glamorous of the translators’ (Nicolson, p. 163). The only one not to take holy orders, he combined the roles of courtier, astronomer and translator. He had a love of mathematics, was England’s foremost astronomer, and the possessor of an eminent knowledge of patristic Greek. To join the company of translators, he broke off work on his 8-volume edition of the works of St John

Chrysostom (eventually published at ruinous cost).

The translators were traditionalists ‘content to leave in place the language of earlier generations that was embodied in previous translations’ (Campbell p. 73). The KJV shows a consistent bias towards older linguistic forms, and a preference for plain language and monosyllabic words. Its use of language is conservative for the time, even archaic in key respects. The pronouns ‘ye’ and ‘thou’ and ‘thee’, and the ‘-eth’ endings used for singular verbs had already ceased to be standard English by 1611.

Rules 3-4 concerned the avoidance of puritan terminology (e.g. ‘Congregation’ for ‘Church’, ‘Washing’ for ‘Baptism’) and, closely related to this, the necessity to stick to traditional

usage when a word had more than one possible meaning. Yet the solemn cadenced quality of the language was not the product of prescriptive rules but a readiness to efface differences in personality in order to achieve an enduring and consistent style of biblical English.

In 1608 the work of the companies was presented at the ‘General Meeting’ or revisal committee referred to under rule 10. Two more years, 1609 and 1610, were spent in review by the six members of the revisal committee sitting in London, then by the Committee of Two who saw the book through the press. The following year the King James Bible was printed for the first time by Robert Barker.

‘The quality of the first edition of KJV, judged purely as a printed book, comfortably exceeded that of any other book printed in the seventeenth century’ (Campbell p. 107). It is of deeply impressive size befitting its place on a church lectern, the 74 preliminary pages add to its weight, the black letter typeface in double columns suits the solemnity of the text, and the margins are uncluttered by extensive notes.

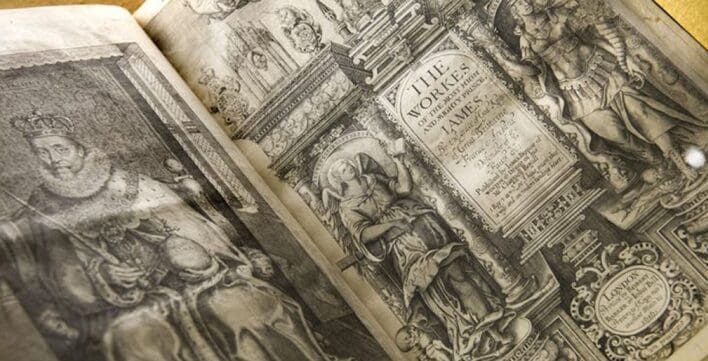

The leaf after the title carries a dedicatory epistle to James I who is revered as ‘the principal mover and author of the work’. Surprisingly though, there is no royal portrait in the first edition. None of the translators are named. The principal decorative features are the engraved general title by Cornelis Boel (see illustration), a woodcut title to the New Testament, and a double-page engraved map of Canaan after John Speed. Woodcut illustrations are restricted to the genealogical tables, and nothing impresses so much as the spacious columns of Holy Scripture, divided into chapters and verses.

There are two issues of the first edition, known as the Great ‘He’ and Great ‘She’ Bibles, one with the incorrect reading ‘and he went into the city’ (Ruth iii 15), the other with the pronoun

corrected to ‘she’. Though both are dated 1611, the ‘He’ Bible is the recognised first issue.

The folio editions published within the first few years are not very rare but, after decades or even centuries of church use, they tend to be in poor condition with pages missing and other imperfections. The $52,500 paid for a first edition, first issue, at a Chicago auction last year was an impressive sum for a defective copy — this was rebound and lacked the title-page, map, last leaf, and six other leaves; 31 leaves at the beginning and end were frayed or torn with loss of text and repaired (Hindman, May 2021). Even single leaves are traded. But complete copies of an early edition are rarely met with.

Of special historical note is the Houghton copy, last seen at auction in 1989. Copies of the first edition do not get better than this one. In place of the usual engraved title, it has a very rare woodcut title previously used for the Bishops’ Bible. The natural assumption is that the earliest copies came from the press before the engraved title was ready, the woodcut title was used as a substitute for advance copies. The Houghton copy also possesses a stunning red morocco binding with a central lozenge built of small gilt tools around the insignia of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (see illustration). In 1979, this copy realised £17,000 in Arthur Houghton’s celebrated single owner sale at Christie’s.

In the ‘Garden sale’ ten years later, competition for it had grown to such an extent that it sold for £143,000 (Sotheby’s, November 1989). If re-offered at auction today when high spots are in such strong demand, £400,000 hammer would certainly be a fair expectation.

Currently, the $396,500 given for the Moore – Silver – Newberry Library copy at the Pyrie sale (Sotheby’s New York, December 2016) is the highest price paid for a first edition. Although this was a record amount, the winning bid of $320,000 (before the addition of premium) was under the ambitious pre-sale estimate of $400,000- 600,000. The Pyrie copy satisfied the demand that a

bibliophile copy be complete. It was also an impressively tall copy, according to the catalogue ‘the tallest copy known’; though rebacked it had kept its contemporary blind-tooled calf covers; and it had belonged to Louis H.

Silver (1902-1963), the great Chicago book collector. Two other first edition copies made big prices at the same period, they were complete but had the disadvantage of being rebound. One made £173,000 (Bonham’s, April 2015), the other the almost identical sum of £167,000 (Christie’s, July 2017). Although a folio size seems integral to the KJV’s character, smaller formats were printed for the benefit of family devotions and private study. The earliest separate edition of the New Testament was a 12mo printed in 1611. The first quarto and first octavo edition of both parts appeared in 1612, printed in roman type. The first black letter quarto edition then followed in 1613. The second folio edition is dated 1613-1611. An apparently rushed response to the quick sale of the first edition, some copies of the second are a mixture of pages from both. A third distinct folio edition, printed in large black letters, made its appearance in 1617.

To add to the possible confusion, there were also small folio editions distinct from the large ones. Up to 1629 all English Bibles were printed by Robert Barker in partnership with Bonham Norton and John Bill. In 1630 Bill’s death and Norton’s imprisonment restored Barker to full control. However, the king’s printer was in financial difficulties which only deepened when a 1631 octavo edition of the KJV omitted the ‘not’ from the seventh commandment in Exodus 20. Adultery was recommended to all. Matters were made even worse because some copies printed the beginning of

Deuteronomy 5:24 as ‘The Lord our God hath shewed us his glory, and his great asse’ (instead of ‘greatnesse’).

As a result ‘the whole Impression was called in, and the printers deeply fined [said to be 300 pounds]’ (Peter Heylyn, Cyprianus Anglicus, 1668). Barker spent the rest of his life in debtor’s prison, and the offending Bible became ‘rare and valuable’ to collectors. The Pyrie copy of the ‘Wicked Bible’ made $47,500 when first sold in 2016, and advanced a little on this figure when resold in 2018. Its big plus was the contemporary blindpanelled calf binding, however the text was not complete.

In Charles I’s reign the monopoly of the king’s printer was ended by the printing of the KJV in Cambridge. The first Cambridge folio, dated 1629, carries the imprint of the university printers, Thomas and John Buck, for the first time. With over 200 changes to the text, it more than compensated for the ‘declining standards’ of the king’s printer. Still more editorial improvements were made in the second Cambridge folio of 1638. Oxford too won the right to print Bibles, eventually exercised in a 1673 New Testament and a complete King James Bible in 1675. The second Oxford quarto (1679) introduced a biblical chronology with dates ‘anno mundi’ rather than ‘anno domini’. The Nativity is dated 4000 years after the Creation.

In the early eighteenth century Bible imprints are dominated by one man, John Baskett, who fought hard to secure a Bible monopoly, partly achieved though leasing the right to print Bibles for Oxford University. Baskett published twelve folio editions of the KJV, the first of which, dated 1717-1716, is the most sought after. Red rules circumscribe its half-page engravings by Vandergucht and text in double columns.

Grades of paper varied and three copies were even printed on vellum at astonishing expense. However, there were failings not in magnificence but in textual accuracy, leading one reviewer to refer to Baskett’s Bible as ‘a Baskett-ful of Errors’. After it got noticed that his version of Luke 20 was headed ‘the parable of the vinegar’ instead of ‘the parable of the vineyard’, it became the ‘Vinegar Bible’.

The folio King James Bible printed in Cambridge in 1763 was also an impressive undertaking. It too was printed on huge sheets of imperial paper but without the adornment of engravings. It strove to attract the reader through the serif typeface designed by its printer, John Baskerville. Despite its relatively late date, the Baskerville connection makes it a valuable Bible today. An average copy will sell at auction for £3000-5000 hammer. The Wardington copy, in contemporary Irish red morocco, still holds the auction record, selling for as much as £18,000, with premium added, sixteen years ago (Sotheby’s, 2006).

Two folio Bibles with eminent editors were published in the 1760s. The Cambridge University Press Bible, edited by F.S. Parris, appeared in 1762, to be followed by the Oxford edition of 1769, edited by Benjamin Blayney. Blayney had incorporated most of Parris’s improvements into his edition which became the standard text for the mass printings of the 19th century.

F.S. Parris, appeared in 1762, to be followed by the Oxford edition of 1769, edited by Benjamin Blayney. Blayney had incorporated most of Parris’s improvements into his edition which became the standard text for the mass printings of the 19th century.

Of great renown in the United States is the Bible printed by Robert Aitken in Philadelphia, 1782-1781. This was the first complete English Bible actually printed in America. A 12mo reprint of the KJV, it became known as the ‘Bible of the Revolution’ and was small enough for Washington’s soldiers to fit into their coat pockets. A worn condition is almost obligatory for it, as it evokes the hard-fought war of American Independence. As many as 10,000 copies may have been printed but a bedraggled copy sold last year for $94,500 (Sotheby’s New York, April 2021). This fell slightly

short of the $118,750 given for a copy with minor losses and edge wear to pages sold a few years earlier (Christie’s New York, June 2018).

It took time for the KJV to become the predominant, and most loved Protestant Bible in English, its use of our language almost mystically linked with patriotism and love of one’s country. As Peter McCullough and Valentine Cunningham point out, the translators themselves were reluctant to give up earlier versions whose use was habitual to them (see ‘After Lives of the King James Bible 1611-1769’ in Helen Moore and Julian Reid, editors, Manifold Greatness.

The Making of the King James Bible, Bodleian Library, 2011, p. 141). However, this was not the case with younger generations who grew up with the Bible of King James. John Donne’s greatly admired sermons, issued in three successive volumes, nowhere deviate from the KJV text.

At the Restoration in 1660 the Bible was reissued, becoming the ‘go to’ text for English religious vocabulary. The Anglican poet George Herbert, and the Anglo-Catholic Henry Vaughan made consistent use of it. John Milton, ‘republican, regicide, enemy of established churches’ and yet the versifier of Genesis and author of Samson Agonistes, a biblical tragedy, seems to have preferred using a Latin Bible; the Greek and Hebrew originals were also totally familiar to him.

Nevertheless, he owned a first quarto edition of the King James Bible, published in 1612. This was poignantly used to record births and deaths in his own family, the first entry being his own birth on 9 December, 1608. Swift, writing in 1712, praised the KJV for its ‘Simplicity,’ preferring its use of English to the contemporary language.

Important links were developed between the Bible and contemporary music. Henry Purcell, ‘the giant of Restoration music’, gave choral expression to the ‘Song of Solomon’ and other key passages of the KJV. In McCullogh and Cunningham’s words (p. 147), nothing ‘did more to ingrain the most loved passages of the KJV into popular consciousness than Charles Jennens’s libretto for Handel’s Messiah (1741-42)’. The source of its ‘masterful textual fabric’ was ‘almost exclusively’ the King James Bible.