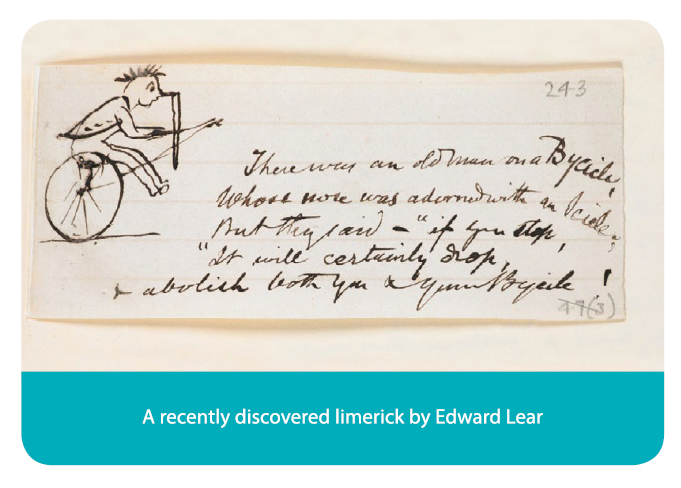

Though not the inventor Edward Lear (1812-1888) was certainly the great user and populariser of the verse form we call the limerick. One example of his work, previously unknown, has just come to light after being long hidden in the Charnwood Autograph Collection in the British Library.

It concerns the inevitable ‘old man’, this time on a bicycle, and was composed for a young lady, Mary Theresa Mundella (1847-1922) whom Lear often wrote to. As the expression of an absurd situation, with an undertone of violence, it is a highly characteristic piece of nonsense:

There was an old man on a Bycicle,

Whose nose was adorned with an Icicle;

But they said — ‘If you stop,

It will certainly drop,

& abolish both you and your Bycicle’.

The unfortunate bicyclist is, of course, drawn in. Lear illustrated all his own poems, demonstrating equal fertility of imagination as a poet and artist. Born in the village of Holloway on 12 May, 1812, he was the twentieth child in a family of twenty-one children. His devoted older sister, Ann, brought him up in a separate home from his countless siblings. Suffering from epilepsy, chronic asthma and weak eyesight, his education was mostly at her hands. His father, a stockbroker of Danish background, had understandable money troubles. Fortunately, Lear’s natural ability as an artist and draughtsman enabled him to earn a living from the age of sixteen, and ultimately win the wholesale admiration of society. Between July and August 1846 he visited Queen Victoria at Osborne House in order to teach her ‘landscape painting in watercolours’. But he was also faced with the difficulties of being a homosexual in the morally censorious climate of mid-19th-century England. While he was to find living abroad easier, he was always a lonely man and this comes across in the sad, forlorn quality of his nonsense poems.

Born in the village of Holloway on 12 May, 1812, he was the twentieth child in a family of twenty-one children. His devoted older sister, Ann, brought him up in a separate home from his countless siblings. Suffering from epilepsy, chronic asthma and weak eyesight, his education was mostly at her hands. His father, a stockbroker of Danish background, had understandable money troubles. Fortunately, Lear’s natural ability as an artist and draughtsman enabled him to earn a living from the age of sixteen, and ultimately win the wholesale admiration of society. Between July and August 1846 he visited Queen Victoria at Osborne House in order to teach her ‘landscape painting in watercolours’. But he was also faced with the difficulties of being a homosexual in the morally censorious climate of mid-19th-century England. While he was to find living abroad easier, he was always a lonely man and this comes across in the sad, forlorn quality of his nonsense poems.

The recently formed Zoological Society of London employed the young Lear as an ‘ornithological draughtsman’. His first publication, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, began to appear in parts when he was nineteen, publication continuing from 1830 to 1832. This exotic publication was based on the Zoological Society’s own collection of specimens, and it was through the Society that he first made the acquaintance of Lord Stanley, later 13th Earl of Derby. The aviary and menagerie at Knowsley Hall, Lord Stanley’s ancestral home near Liverpool, were the largest in the kingdom, eventually occupying 100 acres of land and 70 acres of water.

Lear accepted Lord Stanley’s invitation to reside at Knowsley, which he did on and off in the years 1832-1837. His role as artist in residence was to record the singular-looking birds and mammals in his patron’s zoo, and he became the first major artist to draw birds from life instead of skins. In his leisure time he entertained the children at Knowsley with poems, drawings, alphabets and menus.

He illustrated the limericks he found in Anecdotes and Adventures of Fifteen Gentlemen (circa 1822), and his mind soon teemed with his own. However, he never used the term limerick, preferring to call his lyrics ‘nonsenses’. His charming conversation and piano improvisations were no less pleasing to the adults.

Lear moved to Rome in 1837, joining a circle of expatriate English painters and writers, landscape drawing made less of a demand on his weak eyesight. A ten year sojourn in Italy led to two richly illustrated books, Views in Rome and Its Environs (1841) and the 2-volume Illustrated Excursions in Italy (1846-1847). The year 1846 also saw publication of two other titles. Both contained depictions of birds and animals, and were yet utterly different in character. Gleanings from the Menagerie at Knowsley Hall, a book paid for by his patron, was a folio illustrated with 17 hand-coloured lithographed plates after Lear, a serious work of natural history.

The Book of Nonsense by Down Derry Down was an all-lithographed work in two parts, each bound separately in two oblong octavo volumes, their content seventy-two limericks printed on one side of the leaf only, each with an illustration after the author. Both volumes had the same pictorial front board capturing the moment of uproarious delight when the poet-artist passes his Book of Nonsense to a group of children. The accompanying limerick reads:

There was an old Derry down Derry,

Who loved to see little folks merry:

So he made them a Book,

And with laughter they shook,

At the fun of that Derry down Derry!

Just visible beneath this opening limerick is the date 10 February 1846 and the imprint of Thomas McLean, 26 Haymarket. About 500 copies were published by McLean, and sold at 3/6d.

Lear persisted with the pseudonym of ‘Derry Down Derry’ for the second one-volume edition by McLean which appeared in 1856. This reprint is today rarer than the first edition itself. A third edition, commissioned from Routledge, Warne and Routledge by the author, was published in 1861-62, and became the basis for all future editions. This time, Lear supplied 43 new limericks accompanied by his illustrations; lithographs were replaced by wood-engravings made from his drawings by the Dalziel brothers, who did the printing. Three limericks in the original edition were deemed unsatisfactory and dropped. Lear, who was named as author for the first time, included this dedication expressing how his poems had already given pleasure to two generations: ‘To the Great-Grandchildren, Grand-Nephews, and Grand-Nieces of Edward, 13th Earl of Derby, this book of drawings and verses (the greater part of which were originally made and composed for their parents) is dedicated by the author, Edward Lear’. The dedication is dated 1862 at the foot.

Once the third edition of 2000 copies had sold out, copyright was bought by Routledge who reissued it on a regular basis. Within only two years, it had reached a ‘fourteenth edition’. The first American edition is probably that by Willis P. Hazard of Philadelphia in 1863, copying the Routledge printing of the same year.

After settling at San Remo, Italy, Lear published three more volumes of nonsense with his own illustrations. Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets appeared in 1871. Its most famous poems include ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, written for the three year old Janet Symonds, and ‘The Jumblies’. Both narrate journeys to remote places. But in their romance, the owl and the pussycat go to sea in a pea-green boat, while the Jumblies seal their fate by departing for ‘far’ places in a sieve.

More Nonsense, 1872, was devoted to fresh limericks. Laughable Lyrics. A Fourth Book of Nonsense Poems, last to come out in 1877, included favourites like ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’ and ‘The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò’. Lear’s inventiveness seemed to have no limits. Nonsensical creatures abound in this last volume, as do nonsensical landscapes like ‘the Hills of the Chankly Bore’ and ‘the Great Gromboolian Plain’.

All too commonly the Book of Nonsense was read to destruction. This is especially true of the first edition, whose pages were glued but not sewn together. ‘The two volumes consisted of individual leaves glued to the back with rubber solution; the contents, prone to disintegration, often fell to pieces and were thrown away. Others were rescued, but rebound with leaves missing or replaced in a different order. This did not make for wide distribution, and when a second edition was published in 1855, it too was shoddily lithographed and bound’ (Grolier 32). A census taken by Justin Schiller in 1988 located only 11 complete and 12 incomplete copies of the first edition, though the number of survivals now appears a little higher than that.

In buying a modern edition of Lear’s nonsense verse, it is important to ensure that all his original illustrations are included, and not just a small selection of them. For it is actually the interplay between illustration and text which is the source of enjoyment. If you read the ‘nonsense’ first, it raises the question of how the illustration can make sense of it. If you begin with the illustration, you then want to know how its grotesqueness can possibly be explained in the snippets of verse below. Invariably the focus is on a single individual, separated by one peculiarity from the rest of society and essentially in conflict with it. In some cases eccentricity triumphs over dull conformity, in others it lamentably fails. But the game of seeing how verse and illustration match up together provides endless fun.

Lear had begun to systematically collect and illustrate limericks, some years before A Book of Nonsense appeared in 1846. Evidence for this comes from an amazing 2-volume manuscript notebook filled with drawings and limericks, included in the Edward Lear exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1985. The notebook had first been uncovered in 1981; to then be published by Penguin as Bosh and Nonsense in 1982, at which point it was given an 1860s date of composition. However, the date was revised to the early 1840s by the Royal Academy, and when the notebook was auctioned in 1986 Sotheby’s agreed. The contents were summarised as ‘79 humorous ink drawings and the accompanying autograph verses, each on a separate sheet, numbered 1-80, number 11 no longer present’. 16 of the limericks had never been included in print, while the variation among the drawings was even greater. ‘At least twenty’ were ‘alternative designs, with no similarity to the published drawings’. The notebook left its estimate of £40,000-60,000 behind to reach a figure of £143,000, a sum which would easily be tripled, perhaps even quadrupled, if it went under the hammer today.

Copies of A Book of Nonsense in first edition form which are badly worn and/or defective won’t normally command a big price. Three copies of the first edition came up for auction in 2016, following a period of 12 years in which there had been no recorded sales (see ABPC database). In March 2016, Bonham’s sold a first edition lacking 2 plates for only £800 hammer. In May, the price rose slightly for a much repaired copy lacking one plate. This made $2000 at Swann’s. Such incomplete copies may be destined for framing, if not too damaged. However, the third copy sold at Sotheby’s on 20 October 2016, was certainly not one to be broken up. This was complete, and despite being ‘affected by spotting and browning throughout’, bidding closed at £35,000 hammer, not a bad investment for 3/6d.