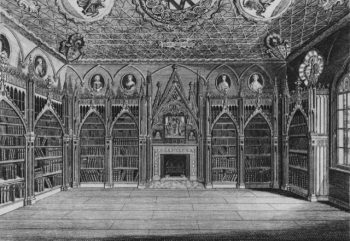

A magnificent library was an integral feature of the country house in both 18th-century England and continental Europe. As much as the pictures, sculptures and lavish furnishings, the array of gilt spines was calculated to impress the visitor, providing opportunities for conversation as well as solitary reading. Volumes come in all sizes and may have been carefully collected or bought by the yard. Past sales may have depleted the collection, even though the shelves look well stocked.

Horace Walpole’s gothic library at Strawberry Hill, ink and wash, published 1784.

However striking their effect when massed together, books are individuals. To appraise the value of each one means checking the date, giving a nod to the author and assessing the market interest. Books printed before 1501, forming part of the history of incunabula, possess great potential. If the author of a rare pamphlet proves to be Daniel Defoe, its attraction is immediately doubled or even quadrupled. A common enough text may have been beautifully illustrated or issued by a famous press. Provenance or marks of ownership may exist in the form of an inscription or bookplate, or as a coat-of-arms on the binding. Association with a well-known historical figure or derivation from a famous collection can push up a book’s value enormously, and then there is its basic feel. Is it in a good state? Is the binding attractive? Does it appeal aesthetically?

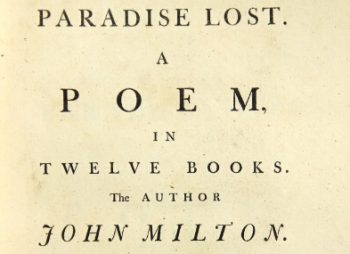

A relatively late edition (1759) of Milton’s Paradise Lost, of value primarily because it bears the imprint of John Baskerville, Birmingham.

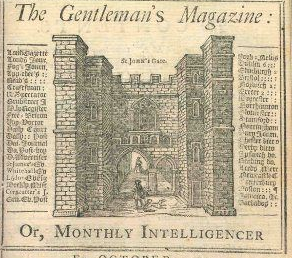

In a big library much of the value may lie in a comparatively small percentage of the books. Whether it be of classical works or native authors such as Milton, Swift, Pope and Gibbon, the reprint element is usually large. Classical works printed after the Renaissance, literary sets and periodicals of the 18th and 19th century, are valued chiefly as shelf fillers — for what pleases the eye rather than the content inside. The Gentleman’s Magazine, which first appeared in January 1731 and continued up to 1922, is probably the most interesting of the literary periodicals. Samuel Johnson contributed to it from the late 1730s to mid 1740s, George Eliot used it to research Adam Bede, it contains maps and plates, but the average auction value per volume is unlikely to be above £30.

Title-page to an early number of The Gentleman’s Magazine, printed by Edward Cave (“Sylvanus Urban”) at St. John’s Gate, Clerkenwell.

With plate books, size really counts. Hefty atlases, engravings or lithographs in magnificent quartos or folios, will contribute in a major way to a library’s financial worth. One would expect to find art and architecture, natural history, horticulture and sport among the topics represented, as they are all connected with the life of a country house. Younger sons often travelled the globe and accounts of foreign travel also have strong potential. The first half of the 19th-century was the great age of the colour plate book. If the most magnificent flower book is Redoute’s Les Roses, John Gould is undoubtedly the colossus of bird books. My personal favourite is his Birds of Australia, published in 36 parts between 1840 and 1848, and bound in 8 enormous folio volumes. The work describes all 681 Australian bird varieties then known (a 5-part supplement was added in 1869).

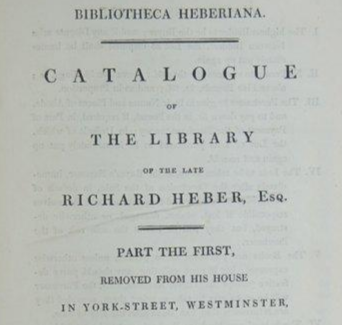

Title-page to part one of the Heber sale whose duration was 26 days. The books sold for an average of only 15 shillings per lot.

Not every 18th- or early 19th-century collection was ostentatiously bound and displayed. Richard Heber (1773-1833) succeeded in amassing some 120,000 volumes, sold on his death in 13 sales spread over three years, with further auctions on the continent. This famous bibliophile, motivated by what Thomas Dibdin called “an ungovernable passion,” gave no thought to presentation. On first visiting his home in Pimlico, Dibdin was dismayed to see “‘rooms, cupboards, passages, and corridors, so choked, so suffocated with books.’” The lack of arrangement was even worse at Heber’s house in Westminster. At 10,000 volumes, the library in his country house, Hodnet Hall in Shropshire, was relatively small in size. But there were also several massive depositories of his books in foreign cities.

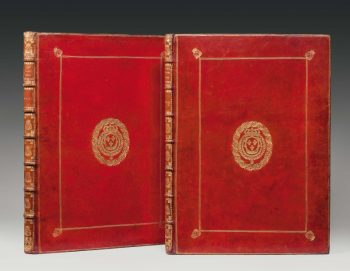

A copy of Claude Perrault’s 2-volume Histoire naturelle des animaux (Paris, 1671-76) in a presentation binding of red morocco impressed with the gilt arms of Louis XIV.

Heber’s “‘inveterate opponent in book battles’”, William Beckford, was appalled by such squalor, arguing that it would be better to burn the great mass of “‘filthy, moulding, overwhelming heaps’” than attempt to sell them. Remarkably, the second Heber sale included almost 50 Shakespeare quartos. On the other hand, there were many books ‘picked up for sixpence or a shilling and whose resale value was practically nil’ (see Arnold Hunt, ‘The Sale of Richard Heber’s Library’, in Under the Hammer: Book Auctions since the Seventeenth Century, edited by Robin Myers, 2001, pp. 143-169).

Samuel Johnson, oil portrait by Joshua Reynolds. As a lowly paid hack writer, Johnson contributed to the Gentleman’s Magazine before publishing his great work of lexicography in 1755.

A modern antiquarian library is likely to have less variety of theme than the calf gilt library of former times, catering for many tastes. The limitations on space are much bigger today, with the result that collections are in general smaller and with a greater tendency to be specialist. However, “high spot” collecting can lead to the crossing of traditional boundaries. A high spot collector won’t accumulate any subject in depth, but he or she will focus on the high spots, the collecting peaks of many different ranges. A Samuel Johnson fan is likely to have an interest in acquiring all or most of his works, whereas a high spot collector might only want a first edition of the dictionary (1755) and nothing else. Ironically, it is the cheaper books rather than the more expensive ones which are becoming harder to sell. The first edition of Newton’s Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (London, 1687) offered for sale at Christie’s New York on 14 December 2016 was not bound in the usual contemporary calf but in superbly tooled red goatskin intended for presentation. Competition for the copy was intense, it had not only high spot but iconic status, and it was finally hammered down for a world record price of $3,100,000.

Rosa centifolia, etched plate from Pierre Joseph Redoute’s Les Roses (3 volumes, Paris, 1817-1824), printed in colour and finished by hand.

Most modern collections are dispersed on a bibliophile’s death, if not sold within his or her lifetime. Collectors get to feel that they have reached the natural limit of their specialism or that they must settle matters for heirs who prefer receiving money to books they can’t appreciate. These sales are often stirring occasions. But the longer the period that a collection can remain unbroken, the more of a phenomenon it is likely to be in the saleroom.

Estelle Doheny, the American bibliophile and philanthropist, was born in Philadelphia in 1875, then moved to Los Angeles with her German immigrant parents in 1890.

Carrie Estelle Doheny (1875-1958), born Betzold, was one of the most renowned American book collectors of the 20th century, and that rare being, a female bibliophile. She met her husband, the Californian oil man Edward Lawrence Doheny, in 1899 while working as a telephone operator for his company. The collection she began forming in relative middle-age was quite closely connected to her beliefs as a devout Catholic (she was created a papal countess in 1939). It grew to some 7000 books and 1300 manuscripts, meriting a 3-volume catalogue published 1940-1955. First given to St. John’s seminary in Camarillo, the collection was eventually sold by Christie’s New York in 6 catalogues 1987 to 1989, slightly over a century after her birth; it made proceeds of nearly $38 million dollars, with volume I of the Gutenberg Bible alone making $5 million.

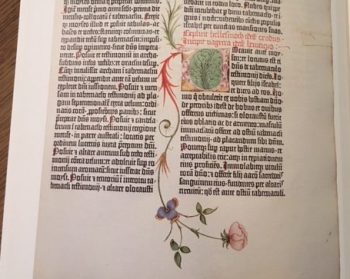

A page of the “Gutenberg Bible” (Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust, 1455) as illustrated in the catalogue of the Estelle Doheny Collection, Part 1, lot 1, Christie’s New York, 22 October 1987

Of much older origins still was the scientific library of the Earls of Macclesfield, removed from Shirburne Castle and sold by Sotheby’s in 12 parts, 2004-2008. This collection derived from the library of William Jones (1675-1749) and was put together almost exclusively in the 18th century; its 2300 works realised the staggering figure of over £20 million.

Call us today to enquire about an appointment on 01883 722736 or email [email protected]